< Interviews

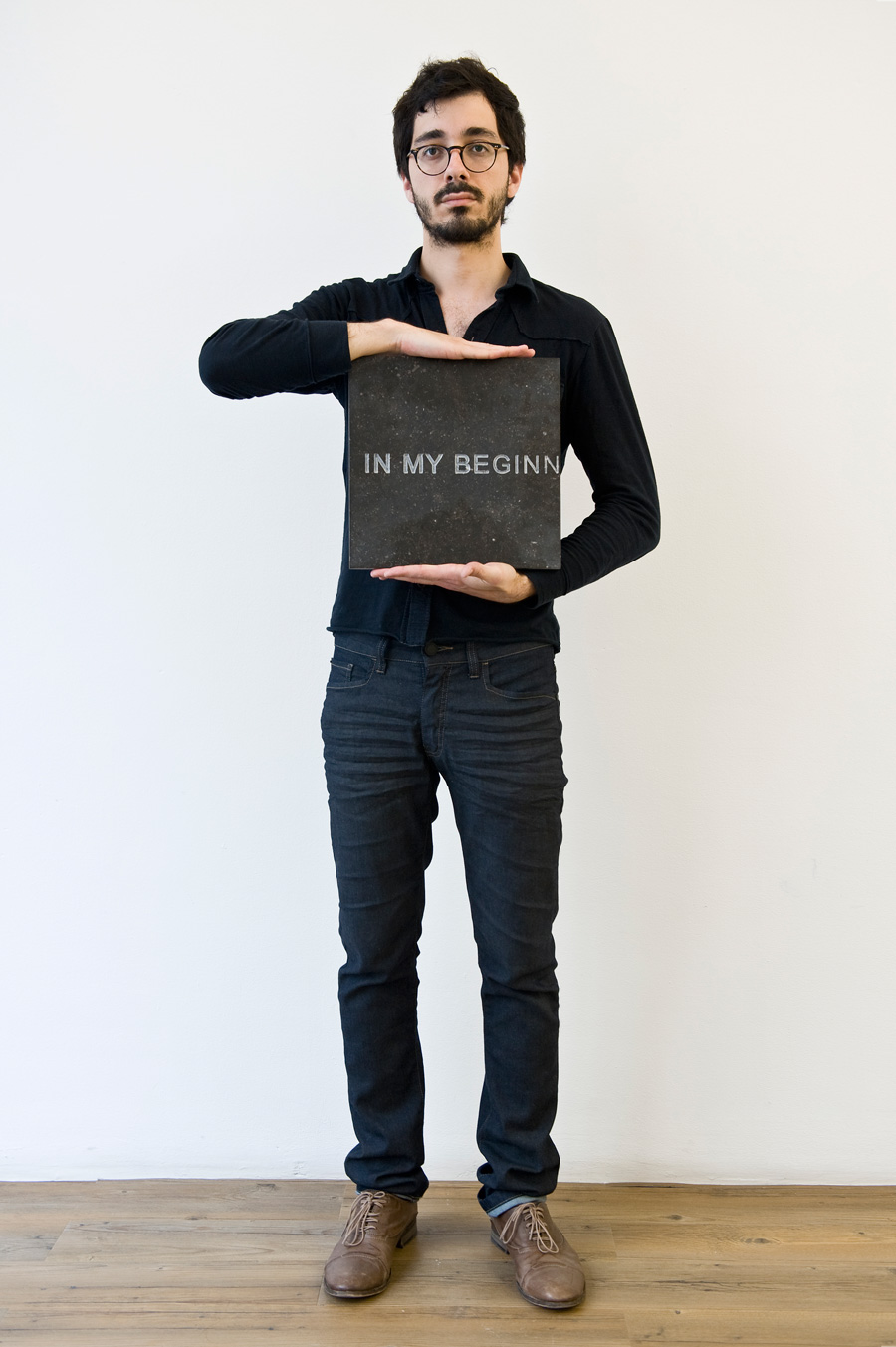

Francesco Arena, Pannello spaccato con testa di nietzsche – Premio Terna 01

Francesco Arena was born in 1978 in Torre Santa Susanna, Brindisi. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Lecce and now lives and works between Cassano delle Murge (Bari) and New York. His research starts out from the recent history of political and social events that have marked the present day. Episodes too often hidden or silenced are brought back to life through essential and allegorical sculptures. «I define myself as a sculptor because my work at heart has a closed form, a core, in which what I see and perceive collapses against other sources and ideas.» There is a centripetal force in his works that attracts and engages the audience in the recesses of time, in a tangible and pervasive experience.

An artist of international renown, he has presented his work in several public and private spaces which include: 55th Biennale (Venice), Art Basel, Monitor 215 Bowery (New York), Monitor (Rome), Nogueras Blanchard (Barcelona), The Italian Academy for Advanced Studies at Columbia University (New York), FRAC Champagne-Ardenne (Reims), Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore (Bergamo), Ermanno Casoli Foundation (Fabriano), Museion Project Room (Bolzano), De Vleeshal (Middelburg), Nomas Foundation (Rome), GAM Galleria d’Arte Moderna (Bologna), Castello di Rivoli (Turin), Fundação Iberê Camargo (Porto Alegre, Brazil), SongEun Artspace (Seoul, South Korea), Galerie Kadel Willborn (Karlsruhe), Teatro Valle Occupatio (Rome), Casa Encendida (Madrid) and Palazzo Belmonte Riso (Palermo). He was the winner of the New York Prize at the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies at Columbia University and the Contemporary Art Prize at Ermanno Casoli (Fabriano), was selected for the LUM Award, the International Award for Young Sculpture of the Fondazione Francesco Messina (Casalbeltrame) and the Furla Prize 2011.

Pannello spaccato con testa di Nietzsche (Panel Split By Nietzsche’s Head) was the winner of the Terna Prize 01 in the Gigawatt category.The installation consists of a splintered panel of industrial plywood which which contains a clay bust of the German philosopher, almost a warning to accept and preserve the history of humanity across distances of space and time and cultural distances in which «the philosopher creates a vacuum and fills it, and the ideas travel to inaccessible places.»

What is the artistic situation in Italy today? What is the role of the artist in the current system of art and society?

Contemporary art is only present in Italy because of a totally private system of galleries and collectors. As for the commitment of the public sector, we are living in a time of very little commitment. Just look at the situations faced by the major contemporary art museums in Italy, often without a director and with no funds to work on long-term projects. We are in the middle of October and we still do not know who will be the curator of the Italian Pavilion at the next Venice Biennale, when the curators for the other countries have been decided well in advance, and rightly so, given the commitment and work that the Pavilion requires. I think that the Pavilion is a representative example of the state of the art in Italy today.

I do not know if the artist’s role in society has changed from what it used to be. I believe that, despite the many institutional difficulties, today it is easier to have contact with work by artists. We live in a country where mobility is now extremely fast, where on the internet we can see the work of so many artists. As a result, the artist is fully integrated into the society in which he or she lives. The artist’s work is a mirror – and probably a distorted one – of society.

The Terna Prize, in one of its early editions, published a forecast of the state of the art world from 2010 to 2015. The results showed what is now the current scenario. Among these, there was also the fact that the crisis would have caused the dominating rules to be subverted, as well as more social involvement in art. Is this really what is happening?

This year has been particularly difficult, including at the level of the market. But we are talking above all about the situation in Italy because, for example, in the US, the art market is already recovering. I don’t know if the crisis has actually led to a greater social commitment in art. I honestly don’t think it has. I think, on the contrary, that it has led to a withdrawal, a return to order. In private galleries we see a lot more paintings, more works which are easily marketable. Right now I think that galleries are unable to deal with costly productions for works which are difficult to sell. I honestly don’t see more social engagement out there. I don’t see the emergence of different channels: an artist needs a gallery to be able to sell, survive and continue working.

Do you remember participating in the Terna Prize? Were you working on a particular project?

I participated in the first edition of the Prize so it was not as well-defined as a situation. At that time I was working on a series of works, attempts to create space in closed structures that had no space. The work presented in the Terna Prize was indeed a panel of industrial plywood that I had splintered in such a way that it became a sort of niche for a clay bust of Nietzsche’s head. The idea was to take something that already existed, something that came from an industrial process ― the plywood panel, to be precise ― and to work it, break it, in a sense to rape it, to create a space that was previously non-existent.

In what direction has your most recent research evolved? Can you tell us about any future projects and plans?

I think that over time, materials change and one can decide to experiment, but the artist’s work remains the same. For two years now I’ve been working more with a classic material – bronze. For me the choice of material is important. In addition to having physical characteristics which lend themselves to certain types of machining, the material has its own ethical quality, its own meaning. Bronze is the material of the monument, of ancient statues and, consequently, brings with it the concepts of time, difficulty, effort, also because it is a material that requires different types of machining over long periods. As for the issues, I am trying to analyze what is around me, what is happening before my eyes: I try to report what I see and know by projecting it ― and distorting it ― through my own view of the world.

In your opinion, how has the meaning of the term and the function of public art changed?

Since public art has to speak to a large number of people, made up of many social situations and cultural levels, it needs to use simple language. Of course, from monuments to the art that we now understand as public, there has been a change in the language and in the form in which it is expressed, but the information is the same. Perhaps today we are more used to perceiving and accepting certain types of art that are anti-monumental and more ephemeral as public art. As a result, it is easier to communicate with a wide audience through an action, a performance or an event of limited duration. We live in a much faster-paced time with shorter distances. We no longer expect to enjoy monuments the way they were enjoyed a hundred years ago. Today there are also temporary stores which respond to this kind of need, or offer a service for a limited time: one knows what time is available in that period to try to figure out what one can give to that thing. Art is always similar to the time when it is produced.

Yours is an art that is markedly political, or rather, where politics and history play a leading role, before being translated into experiential and creative forms and formulas. What are the literary references that lie behind this transversal search?

Usually I become aware of a story or I have always known it and at some point I decide to delve deeper into it. At that moment begins a period of studying and researching all the sources. I always try to define this study phase very well because I feel that the suggestion that triggers a creative process should not become a kind of historiography and that we should rather leave room for interpretation by the artist. My sources are many and varied: films, books, songs and sometimes just the sight of a place. Culturally they are Catholic, linked to the idea of pilgrimage, of going and seeing the places where the events occurred. For me it is important to enjoy a specific situation or space with my body, and not for nothing are my works based on the traces made by the meeting of my body with the space and the traces left by history.

What should Italy have (that it does not already have) to encourage creativity and make our country even more competitive at international level? And which country do you believe to be the best from this point of view?

I think the art academies, as they are structured, are now obsolete. Some continue to be important thanks to the people who teach there, that is, excellent fine art historians or wonderful artists. But being a good artist does not automatically make you a good teacher. I think the first problem is the question of teaching. We do not have any academies comparable to those in Germany or the US colleges. This makes us uncompetitive internationally. No foreign gallery owner would come to see year-end exhibitions at the Italian academies as they do in England, Germany or the USA. I think that for the work of the artist, adversity is a good thing. I do not believe in a form of creative welfarism. I think, instead, that everyone should find their way to work and defend their own work. What is certain is that if a foreign museum decides to put on a show for an Italian artist, it is very difficult to be supported by the Italian Cultural Institutes abroad or the embassies. If, however, an Italian museum, but also even a gallery, puts on an exhibition of a Dutch artist, it is almost certainly able to obtain funds to cover transport and insurance. These are small things that I think they make all the difference. For example, I prepared a book which covered ten years of work by two foreign institutions, the FRAC Champagne-Ardenne in Reims and the De Vleeshal in Middelburg, in the Netherlands. I was unable to find an Italian institution that wanted to participate in this project.

What does the Terna Prize represent, today and in the past, for an artist in the Italian and international scene?

The Terna Prize is an excellent opportunity to showcase one’s work and to also see it recognized. For an artist this is very important because it is the thing that drives you to produce and to go and see the work of others. It is right to create different categories because it would be unfair to compare the work of artists in their forties with that of artists in their twenties. I won in the young artists section against artists with similar work experience. The Prize should be used to support the work of an artist. This means creating something that goes beyond the prize money and the purchase of the work. It could be a good idea, especially for very young artists, to give them the opportunity to participate in residencies abroad, to enable them to broaden their horizons. Two years ago I won the New York Prize and I spent four months at the ISCP. It was a great reward because it allowed you to spend four months in New York with a good salary. Whether you spend it at the ISCP or anywhere else is relative: When you are in a city that is like a cauldron, with so many things to see, the important thing is to be there. For a young artist, being able to spend a few months in New York without the hassle of having to pay the rent is an excellent opportunity.