The article represents the first paper for the project “Eternal Body. Human senses as a laboratory of power, between ecological crises and transhumanism”, curated by Elena Abbiatici. This rearch has been organised thanks to the support of the Italian Council (IX edition 2020), an international programme promoting Italian art under the auspices of the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities and for Tourism.

In Smoke Flowers (2017) Belgian artist Peter de Cupere makes real flowers, both large and small, release industrial air pollution by discharging smoke[1], as if taking revenge on man. The flowers’ scent is gradually lost, absorbed by the gases produced by pollution.

According to a mathematical model developed at the University of Virginia (USA) in 2008 and carried out by environmental health researcher Jose Fuentes, the odour molecules emanating from flowers in low-pollution environments travel up to 1000-1200 metres, while in more polluted places they travel only 200-300 metres[2]. These molecules consist of fine dust, exhaust fumes and pesticides that “feed” the plant and destroy the scent emitted by petals and buds.

In the mid-1990s, advances in cell biology and genetics began to provide evidence that the ozone we breathe in the lower layers of the atmosphere could be damaging DNA in alveolar macrophages – a type of white blood cell to be found on the surface of lung alveoli, responsible for eliminating all potentially harmful substances, and in tracheal endothelial cells. It was Lilian Calderón-Garcidueñas, an environmental health scientist at UNAM (now at the University of Montana) who began studying the relationship between ozone, other air pollutants and damage to the olfactory epithelium.

Other olfactory impairments have also been found in connection with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and autistic spectrum disorders (…)[3]. The location of the olfactory bulb in the brain, hidden just behind the eyes and closely linked to the limbic system, would help explain why so many people with olfactory problems also develop a more severe form of depression. All scientists agree on the vital importance of the sense of smell: essential essences are incredibly influential on our psyche, establishing a deep connection between body and mind.

The phenomenon of anosmia (loss of smell), sometimes in combination with loss of taste, is also a reaction to the coronavirus infection and often its only symptom. This loss can last for several months and is by no means of minor importance since the cells responsible for protecting and supporting the olfactory neurons have been damaged.[4]

To address this loss of our sensory and olfactory heritage, ODEUROPA was launched in 2020. This is the first European initiative to apply artificial intelligence techniques to four centuries of olfactory notes preserved in historical European images and texts. Odeuropa is an international research project, funded with €2.8 million from the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme, aimed at keeping alive smells and scents that are gradually being lost and investigating the importance that scents have played in shaping our communities and traditions. The information collected is stored in a database called the European Olfactory Knowledge Graph, led by academics from the UCL Institute for Sustainable Heritage (ISH) for the preservation and communication of historical scents. Between 2021 and 2023, a number of European museums will host and share Europe’s key scents, allowing everyone to experience the past through perfume.

Sissel Tolaas, a Norwegian artist and researcher, began the task of capturing the smells of autumn flora in Central Park, NY, in 2004: the complex smells emanating when plant life starts to die.

Tolaas, known for her research into the olfactory invisible, spent about a week in Central Park collecting and sampling perfume molecules using a customised extraction method. At the “Re_Search Lab” in Berlin, supported by the chemical manufacturer International Flavours & Fragrances Inc., the artist together with a team of researchers and developers later broke down and analysed the individual molecules, extracting data on the various types collected. Through a subsequent process of “microencapsulation” of odoriferous molecules reproduced in the laboratory, in 2016 Tolaas created Smell, The Beauty of Decay: SmellScape Central Park, a special olfactory and tactile installation for the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. The wall is covered with a scented paint, which visitors can scratch in order to breathe in the smell of polluted flowers from different parts of the park[5].

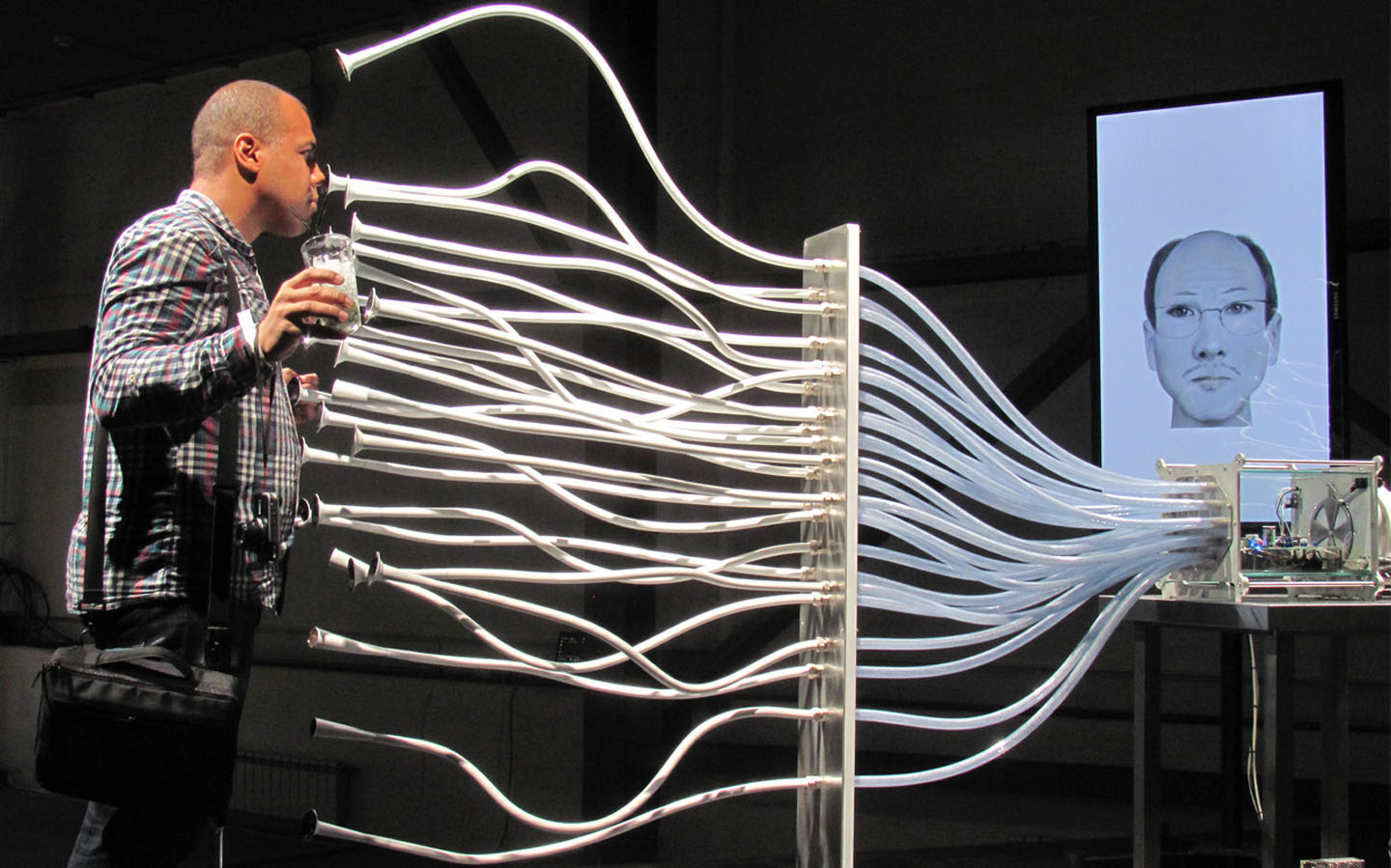

Odour pollution is yet another mode of political control which is exercised over our senses. The Russian collective Where Dogs Run, with reference to the dark side of contemporary technology, suggests how the sense of smell can become a tool of biometric control in the hands of power. The collective is formed by Natalia Grekhova, Alexey Korzukhin, Olga Inozemtseva and Vladislav Bulatov. Their artistic statements are subtly conceptual and subversive, both utilising and reflecting on the power of the media. In the tubes that are part of the installation Faces of Smell (2012)[6] gas detectors and analysers are placed to collect information about people and their position at a precise moment through their smell and breath. When a person approaches the gas analyser and sniffs the tubes, the tubes sniff them in turn. Once the air composition data is processed, it compiles and produces a face – a witness to its position, shape and facial features at that particular moment. In short, a person sees a face conforming to their own smell, exactly in line with current requirements for continuous tracking. Surveillance capitalism is also analysed through the design of smell and related explorations triggered by it.

The control of odour and the olfactory atmosphere in different environments is an ancient practice which in the Middle Ages saw the abolition of any fragrance considered intolerable to Christian morals, with the exception of incense for to its religious use. Then again, at the beginning of the modern era, this control represented a progressive cleansing of the racialised odour along with the body of the black slave – malnourished, tortured and overworked. “Whiteness often symbolized virginity, purity, and floral essences, and blackness was marked by an inherent dirtiness, sinfulness, and odor”, says Andrew Kettler in The Smell of Slavery (2020). Sensory imperialism in colonial times passes through the condemnation of the “stench” of the slave trade and related denial.

The Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga in the installation Anamnesis (2016), presented at the Museum of Conteporary Art of Chicago, investigates tension exerted by white colonialism between, on the one hand, the contempt and masking of natural smells and, on the other hand, the exploitation of the workforce that instead cultivated spices and herbs for export[7].

Coffee beans, tobacco leaves, cloves and other spices exploited in the “race for Africa” have been inserted into a river-shaped wall engraving. They invite us to question our interaction with them. As in the philosophical tradition, both Kant and Hegel have denied smell as a basic condition for authentic works of art, Anamnesis becomes an opportunity to deny this assumption, recognizing the absolute artistic use of African spices and smells to evoke and problematize colonial dynamics that have long been silented[8].

The geographical and cultural affiliation of odours is an important issue, underlying cross-cultural olfactory tests to assess performance in terms of odour threshold (sensitivity), odour discrimination and odour identification. This is similar to the Cross-Cultural Smell Identification Test, a universal test which is valid for any culture or geographical origin, developed by two researchers led by Richard L. Doty, professor of psychology in the Department of Otolaryngology at the University of Pennsylvania. Banana, chocolate, cinnamon, petrol, lemon, onion, paint thinner, pineapple, rose, soap, smoke and turpentine would appear to be the twelve scents considered familiar to the cultures of North and South America, Europe and Asia.

[1]The work was exhibited in Venice, as part of the collective exhibition “Command-Alternative-Escape”, held in the Tethis space during the 57th Venice Art Biennale. https://vimeo.com/214104335

[2] Fariss Samarrai, FLOWERS’ FRAGRANCE DIMINISHED BY AIR POLLUTION, UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA STUDY INDICATES, 10 April 2008, Journal of University of Virginia https://news.virginia.edu/content/flowers-fragrance-diminished-air-pollution-university-virginia-study-indicates.

[3] Carrie Arnold, Sensory Overload? Air Pollution and Impaired Olfaction, Environmental Health Perspectives https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/EHP3621

[4] Society for Neuroscience, Sniffing COVID-19 Out: Studying the Nose to Understand the Coronavirus, Fall 2020; url: https://www.sfn.org/publications/neuroscience-quarterly/fall-2020/sniffing-covid-19-out-studying-the-nose-to-understand-the-coronavirus.

[5] Alex Palmer, Can Smell Be a Work of Art?, 23 February 2016, Smithsonian Magazine; url: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/can-you-smell-work-art-180958189/

[6] https://zkm.de/de/node/26703/s-z#faces-of-smell; https://www.digitalartarchive.at/database/general/work/installation-faces-of-smell.html

[7] Jonathan P.Waats, What 2020 Taught Us About Smell, 3 December 2020, Frieze Art Magazine https://www.frieze.com/article/what-2020-taught-us-about-smell

Partners: Arshake, FIM, Filosofia in Movimento-Roma, Walkin studios-Bangalore, Re: Humanism, Unità di ricerca Tecnoculture – Università Orientale di Napoli, GAD Giudecca Art District-Venezia, arebyte-Londra, Sciami-Roma.

images: (cover 1) Peter de Cupere, Smoke flowers, 2017. Installation. Flowers and Scents With/thanks to the support of IFF (Bernardo Fleming, Meahb Mc Curtin, Laura French, Gregoire Hausson, Marine Hetheier). Photo by Peter de Cupere (2) Installation view of Smell, The Beauty of Decay: SmellScape Central Park, Autumn 2015, 2015–16. Designed by Sissel Tolaas. Sponsored by IFF (International Flavors and Fragrances, Inc.). Microencapsulation. Commissioned by Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Photo by Matt Flynn © 2016 Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (3) Where dogs run, Faces of smell, 2012, Interactive Installation, metal, plastic, glass, stainless steel, aluminium, silicone, gas sensors, photoion detector, electronic components, fan, microcontrollers, computer, plasma screen, stand, cutting table, range finder. Programming: Denis Peremalov. Photo by Where dogs run (4) Installation view, Otobong Nkanga, Anamnesis, 2015, image via