Exactly three years ago, in the autumn of 2020, in the midst of the second pandemic wave, the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin presented an incredibly accurate exhibition on the legendary and fascinating Bilderatlas Mnemosyne by the German art historian and critic Aby Warburg (1866-1929), only to close it immediately due to restrictions to contain the virus. The period, we all remember, was flourishing with dull ‘virtual exhibitions’ and all of us, frustrated and embittered, wandered with our mouse over these optical illusions, 360-degree panoramic photographs of museum rooms with a grotesque wide-angle ‘stretching’ at the extremes, which in the movement of the cursor became as if liquid, false in their essence of both exhibition and image. This exhibition is no different, and it is still possible to “visit” it digitally from the website of The Warburg Institute. But let us go in order.

There were actually two exhibitions and if this one presented the Mnemosyne archive, another, at the Gemäldegalerie, presented a collection of 50 objects depicted in the Warburg Atlas from 10 Berlin state museums. Both exhibitions were intended to pay homage to the great inaugurator of a strand of art history that did not exist until the beginning of the 20th century: iconology.

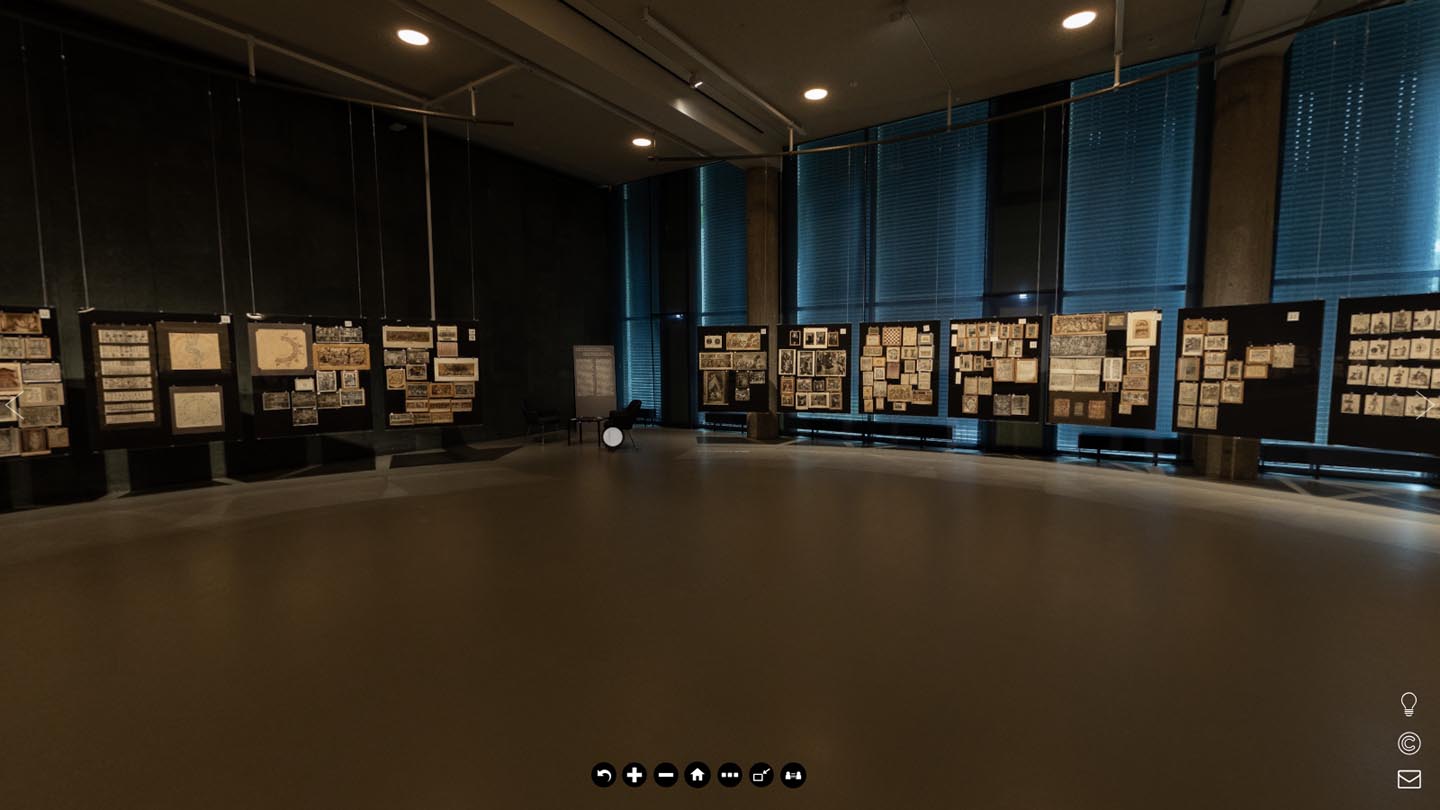

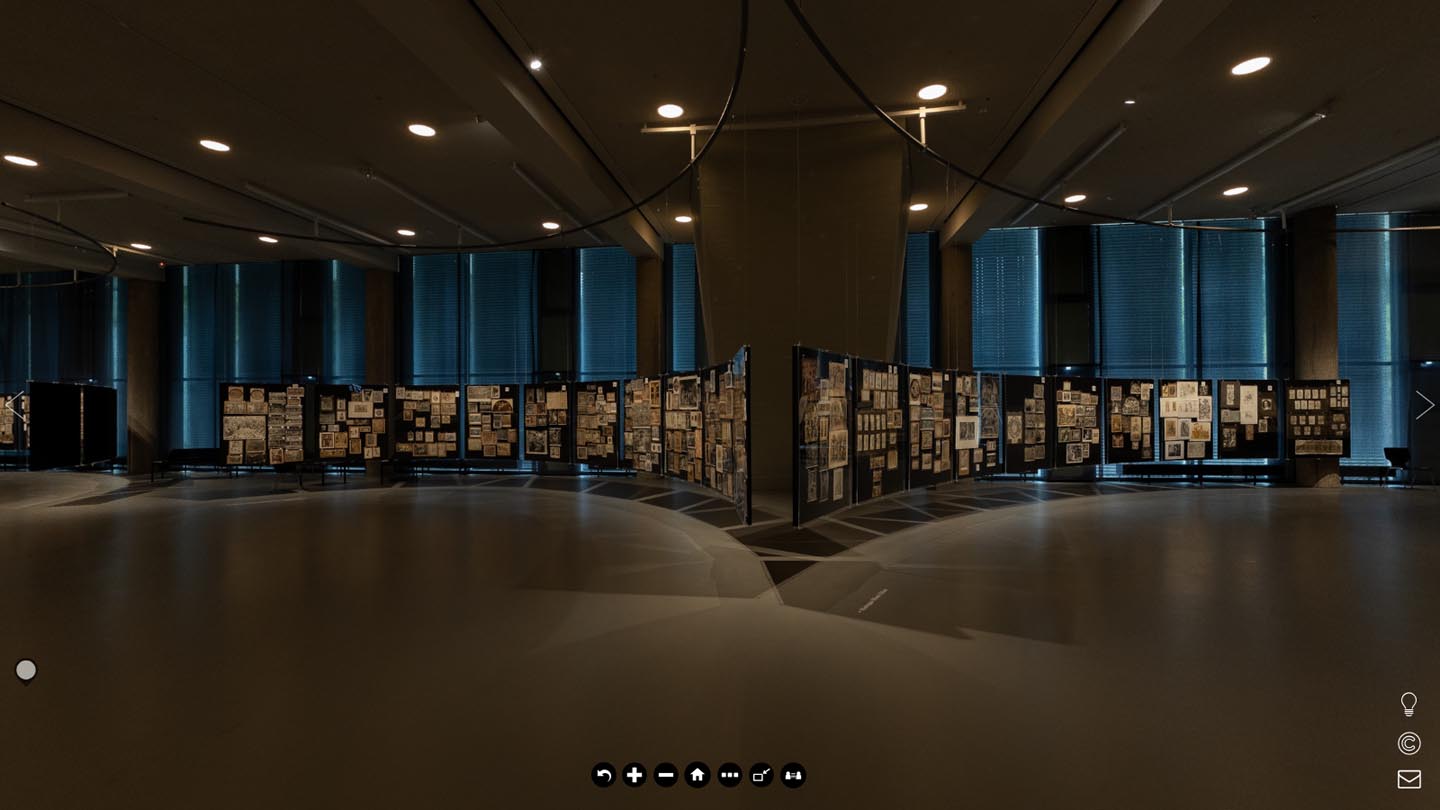

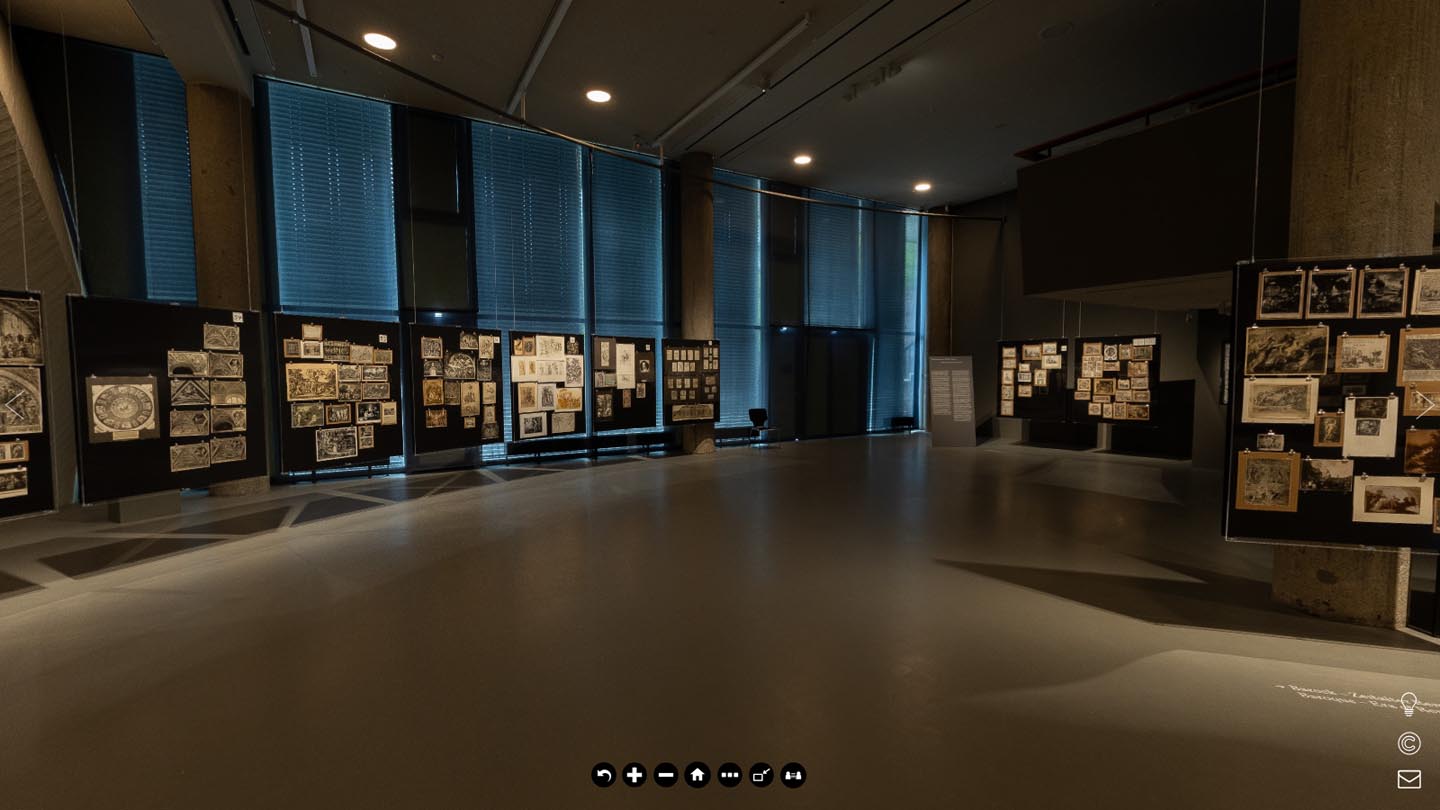

The exhibition in question presents his most important work (critical but also artistic, had it been done in the 1960s it would have been called ‘conceptual’): the Mnemosyne Atlas – reconstructed through extensive documentation that the historian had produced before his death. We are talking about a series of black panels placed side by side, each one loaded with images spanning temporally across History and spatially across the Earth, demonstrating the migrations and survivals of ancient images in modern culture, demonstrating, simply put, the iconological sense of art history.

The room in which these 63 panels are exhibited is perfect: huge, it allows the panels to relate to each other, as was Warburg’s intention, as each panel has a theme but then each theme can be found and can be “connected” to another through a sign, an object, a real link, an ante litteram hypertextual connection, a digital appearance in the mechanical, at times electric, society of the early 20th century.

And so Warburg’s Atlas acquires a new value seen through the eyes of the contemporary, it acquires a digital character, a “contemporary” way of thinking about the image, extremely suitable for an online fruition, in which each panel, with its images ordered and related to a theme, appears to us almost like a refined Google Image search, which, in its essential dynamics, is strongly linked to iconology. In fact, each search brings us before an immense picture gallery of images representing at different times and in different spaces what has been searched for, maintaining a common factor, a constant image character.

And we come to the simulacrum of the exhibition, its virtual counterpart. The virtual exhibition is, in general, in line with the other experiments of this kind, echoing to some extent the use of Google Street View to move from one side of the exhibition to the other and with the possibility of zooming in on the works we wish to see better. As mentioned, Warburg’s enormous oeuvre lends itself particularly well to this digital translation; the spatial qualities of the exhibition, on the other hand, hardly lend themselves to it. The Google Street View effect inevitably transforms the ‘visit’ into a didactic game that differs from the analogue exhibition’s meaning, fortunately, however, zooming in on the images we wish to contemplate digitally is extremely accurate, unlike most exhibitions similar to this one (except for a few secondary panels that are open to the fascination of pixellisation, of a much lesser quality, it is impossible to see them well, incomprehensibly).

This does not detract from the fact that there would be some questions to ponder about Warburg’s project, which is extremely at home in digital space and can be translated into pixels much more easily than most contemporary works of art would be. Why not create an appropriate virtual medium for the work? Why limit yourself to a Google Street View of the exhibition, focusing only on its visual and mimetic qualities? Why not build a virtual archive (Mnemosyne is no more than that) in which the hypertextual links inherent to the project could be revealed between the analogue panels? Why not allow the Internet user to relate, with a special digital tool, the different images of Mnemosyne as we analogically do through the movement of our eyes and our bodies, which is difficult to replicate perfectly in digital form? Could this not have been an extra element of the exhibition, enhancing it with technological qualities, instead of being a two-dimensional simulation usable through a screen, which can only have something less than it?

In conclusion, anti-Covid policies killed an extremely interesting exhibition, now we are left with its virtual reproduction, which shows us perfectly the signifier but less the meaning of it. Obviously this has a positive side, the exhibition is, thus, potentially viral, everyone can ‘visit’ it from all over the world and all the time, but what a waste not to exploit the digital potential, relegating it to a mere impaired simulation of the real. The Bilderatlas Mnemosyne is an important element in understanding our visual culture and the concretisation of Warburg’s studies and genius. With this virtual exhibition we can touch it and be fascinated by it, but we cannot immerse ourselves in it, the level of attention drops quickly in front of the screen and another way of presenting the exhibition, alongside its digital mimesis, would certainly have improved fruition. It is not so much the high-definition photography that makes an analogue exhibition a digital exhibition, but its design that differs from its analogue counterpart.

La mostra alla su Bilderatlas Mnemosyne di Aby Warburg, creata a causa del COVID è tutt’oggi visibile nella sua estensione virtuale.

Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas Mnemosyne exhibition at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Virtual Tour

images: (cover 1) Aby Warburg, «Bilderatlas Mnemosyne», detail (2-5) Aby Warburg, «Bilderatlas Mnemosyne» at Haus der Kulturen der Welt di Berlin, installation view.