Art and Science. From Futurism to Multiplied Art

Italian Futurism has received continuous and increasing critical attention. Through a short excursus into some of the most experimental artistic trends that have accompanied the economic and cultural transformation of XXth century Italy, we shall emphasize how the real Big Bang of the great changes that occurred in the languages of art is to be found in the theoretical tenets of the Futurist movement.

Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe

The present article was written at the time the Guggenheim Museum press office was releasing the news of the great New York exhibition devoted to the Futurist movement, opening on 21 February 2014. For once, Italy was called to take up the role of exporting country, especially of what came to be the most important and internationally recognized artistic movement of XXth century Italy; a movement whose cultural and economic value (given its identity, brand, and visibility) has never been adequately assessed or exploited. The exhibition in preparation tells of an important moment of Italy’s art history and features 350 items, a number barely sufficient to describe the complex history of this avantgarde. Although Italy has been generally recognized as the forerunner of several among the most modern artistic trends (Dadaism, Surrealism, Constructivism, Neoplasticism), still it appears substantially incapable of conferring value to its own renowned past. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Futurism were «legitimized» only at the end of the 1980s by the important (Swedish) art historian Pontus Hultén, former director of the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Hulten was the curator of Futurismo & Futurismi, held at the newly renovated venue of Palazzo Grassi in Venice, and gathered in one single exhibition the most important masterpieces scattered throughout the world [2]. Similarly, the American exhibition at the Guggenheim, which has required something like six years of work and covers a large span of time—from the birth of Futurism with the publication of the first manifesto in the Paris Le Figaro in 1909 to the death of its founder and deus ex machina Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1944—is wide and varied. It focuses on the multidisciplinary complexity of this artistic movement, without the overblown distinction between the origins of Futurism, corresponding to the first two decades of the century, and a ‘second’, later Futurism (1930s and 1940s).

Art, Technology, Science

What kind of connection can we envisage between a celebratory event dedicated to a critical-historical revisitation of The Futuristic Reconstruction of the Universe and technology or science? Broadly speaking: is there a common space shared by the visual arts and science? One should credit Marinetti and the Futurist movement for having understood that in modern society culture is in large part technological and aesthetical. To the eyes of its protagonists, the present century is undeniably getting more and more visual, as the preponderance of images in mass media is increasing. Also, it is apparent that technology pervasively affects and transforms every aspect of daily life. Futurism’s main goal can be summed up as an impetuous and incendiary attempt to bring modernity to Italy. From the great Futurist Big Bang, through an evolving and experimental process lasted several decades, a new set of artistic trends and authors stemmed, which can be grouped under the definition of «exact art». They have been borrowing ideas, methods, and reflections from scientific disciplines or from the results of scientific research. In the end, there cannot be evolution of a given culture without experimentation, including that performed on the languages of art.

Methods and Processes

Can we speak about art by using a method that is scientific, repeatable, falsifiable? We shall see some examples of how this method has been developed and applied, either by recurring to a highly experimental method aimed at offering innovative solutions and languages to the visual communication (in which case, the artist turns into a researcher); or by establishing a fruitful relationship with the industry through new technologies and the innovative use of new materials (in some sense, here the artist becomes a producer). In the background of these great transformations involving the very role of the artist within an advanced industrial society, there is the aesthetic-philosophical attempt to provide a visual representation of the unsteady form of the world; a world simultaneously complex and fragile, which is undergoing a rapid and radical transformation, and for which we can borrow Umberto Boccioni’s words: «in reality rest does not exist.»

Contaminations

Over the last century, artistic disciplines were influenced by great scientific and technological discoveries such as non-Euclidean mathematics, the theory of relativity, the conquest of the space, the discovery of new chemicals and materials (just think, for example, to plastic and to the research done by Nobel laureate Giulio Natta), or by the emergence of new disciplines such as cybernetics, Information Theory, fractal mathematics, the theory of complex systems, subatomic physics, and much more. Technological inventions like the airplane, photography, cinema, radio, TV, copiers, and computers also had a deep impact on the artistic thought. Scientific discoveries and technological inventions have often produced paradigm shifts in the languages of art. (The article continues on Arshake next week…)

«Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe» Guggenheim Museum, New York, 21.02.2014– 09.0 1.2014This is the first of the four parts of an article by Luca Zaffarano that originally appeared in Italy on the magazine «Ithaca.Viaggio nell a Scienza/Ithaca. A Journey into Science», n. III, February 2014, http://ithaca.unisalento.it/nr-03_04_14/Ithaca_III_2014.pdf (original title: Arte e Scienza. Dal Futurismo all’arte Moltiplicata). The magazine is born as an initiative of the Department of Mathematics at the University of Salento and it opens to the cross of a variety of disciplines This article was translated from Italian by Francesco Caruso.

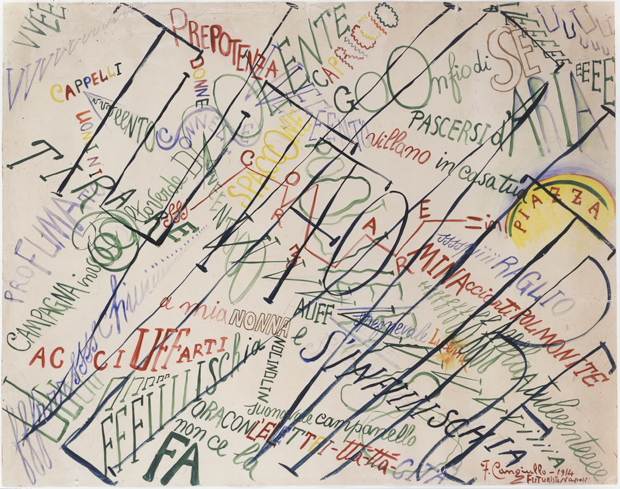

image(1 cover ) Giacomo Balla – The Hand of the Violinist (The Rhythms of the Bow) (La mano del violinista [I ritmi dell’archetto]), 1912. Estorick Collection, London – © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome (2) Francesco Cangiullo, Large Crowd in the Piazza del Popolo (Grande folla in Piazza del Popolo), 1914. Private collection – © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome (3) Installation view: Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 21–September 1, 2014. Photo: Kris McKay © SRGF (4) Tullio Crali, Before the Parachute Opens (Prima che si apra il paracadute), 1939 – Casa Cavazzini, Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Udine, Italy. Photo: Claudio Marcon (5) Filippo Masoero, Descending over Saint Peter (Scendendo su San Pietro), ca. 1927–37 (possibly 1930–33), Gelatin silver print, 24 x 31.5 cm, Touring Club Italiano Archive.