Christiane Paul talks about the relationship between art and the internet, particularly in times of the pandemic, NFT and the financial bubble, but also about counter-culture in the blockchain, all through her rich and multifaceted experience as a theorist, curator and professor of media art. Christiane Paul is Professor at The New School and the Curator of Digital Art at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Paul has written and lectured worldwide on new media art topics. She is the author of “Digital Art”, an anthology on digital art from the 1980s to the present. In 2016, she received the Thoma Foundation’s 2016 Arts Writing Award in Digital Art.

Elena Giulia Rossi: Since 2001 you have been building the artport portal for the Whitney Museum of American Art through online commissions. Since the pandemic the whole world has gravitated towards the web. Galleries have doubled their space to display and sell physical works online, while museums have filled their online calendar with all sorts of events. Has anything changed in the way you see artport after this shift? In what way has it affected the choice of your commissions (if it has, in fact, affected them)?

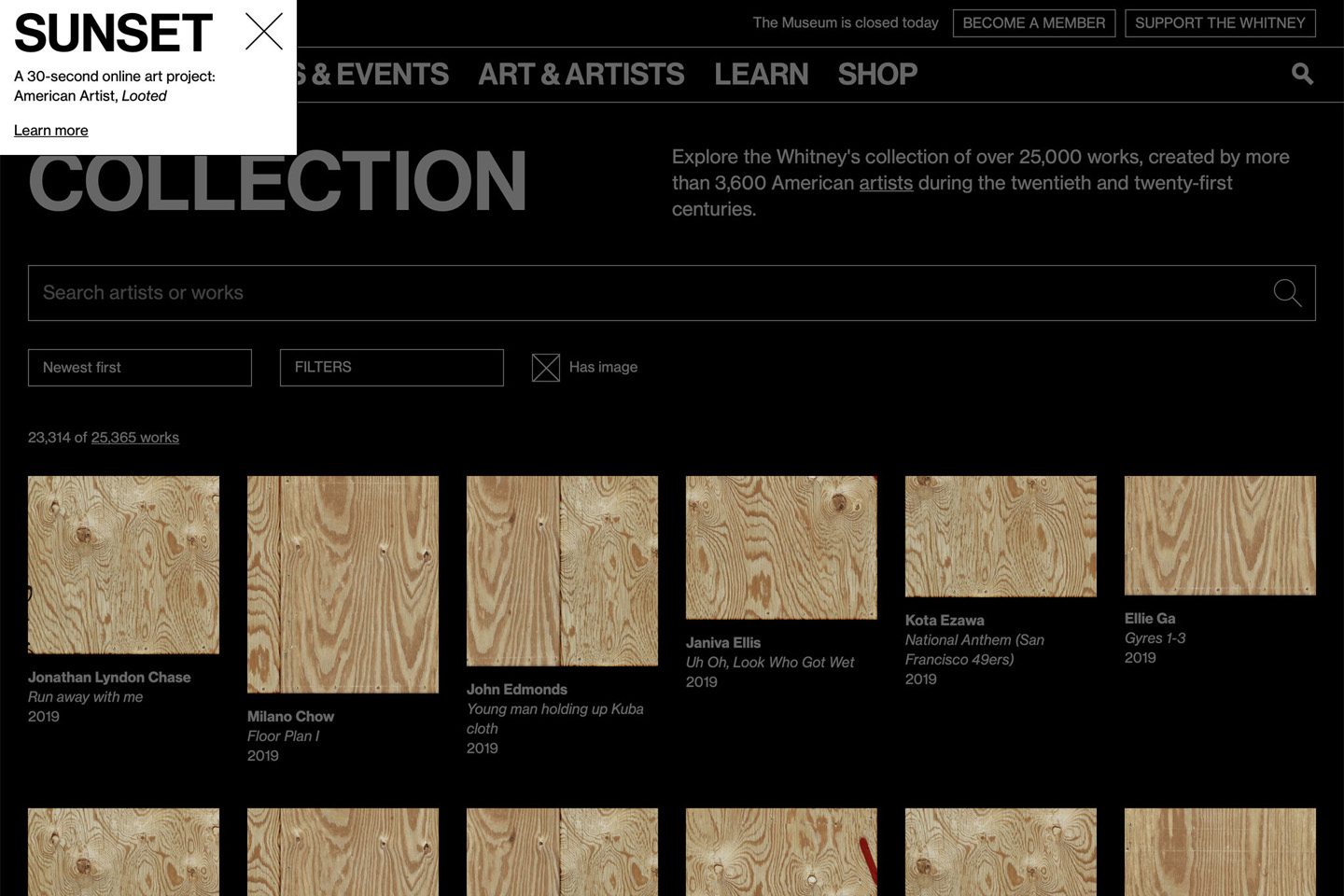

Christiane Paul: One of the silver linings of the pandemic was that it brought more attention to Web-based art. Net art was the only art form accessible during the lockdowns since it uses the Web as a medium rather than platform for virtual tours and representation of physical art in the galleries. Artport definitely received more attention than usual, being featured on radio programs or as the Critic’s Pick in Artforum. Some projects, such as New York Apartment by Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne, which turned New York into one huge, interconnected apartment at a time when people were locked down in their homes, or Looted by American Artist, who chose to “board up” the Whitney’s website at a time when museums were covering their glass windows during the anti-racism protests, just naturally aligned with current events. However, artport’s mission or curatorial goals didn’t change and there was no compelling reason to make a conceptual shift. The site has always tried to introduce visitors to net art within a museum context and to chronicle how the medium has developed over time, reflecting on new technologies or subjects with cultural urgency.

Your artport’s online commission program includes the “Sunrise/Sunset” series. I believe this series represents a very interesting way to interact and connect with the museum’s main website, but also with time, considering that in order to view the works we have to synchronize our time with sunrise and sunset in New York…

The Sunrise/Sunset series is one of my favorite experiments with net art since it is both performative and ephemeral. As a series of small performative projects that take place every morning and every evening at the time of sunrise and sunset in New York City, it is temporally specific rather than viewable at any given time as net art usually is. One could see that limited time frame as a drawback, but at the same time the virtual real estate occupied by the artworks is expanded. The pieces take over the complete website of the Whitney Museum for thirty seconds, unannounced, which is a fairly radical intervention. Anyone visiting the site at the time, be it to learn more about exhibitions or programming, might be interrupted by a glimpse or view of these Sunrise/Sunset projects. Each individual project typically runs for a few months, and the pieces are then accessible online only through documentation. The series encapsulates the ephemeral temporality of performance in a daily occurrence synced to the natural cycles of light.

The merging of the word ‘digital art’ with economic transactions as part of the mania for NFTs is just one example of the (mis)usage of terms, such as digital art and net art. As always, there is a counterculture that critically responds to the system in the same way that net art did in earlier times. What are the creative voices that you consider the ones to have taken the most effective position against this new system’s developments?

Artists were involved in the conceptual development of NFTs from the start, and we are seeing an increasing number of projects that don’t just hang jpegs on the blockchain but use it as a medium. In May 2014, I attended Rhizome’s annual 7×7 initiative at the New Museum where Kevin McCoy and Anil Dash presented their business concept of “monegraphs”, short for monetized graphics. Monegraphs were proto-NFTs — conceived to support artists and creators and relying on smart contracts that included royalties and permissions for sharing and remixing — and I saw a huge potential in them. The technology wasn’t quite there yet, and the start-ups that tried to use tokenized sales contracts and certificates of authenticity folded. Artistic exploration of the blockchain also took off at the that time. The British arts organization Furtherfield, run by Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett, already published a book titled Artists Re:thinking the Blockchain in 2017, highlighting artworks that conceptually explored the potential of organizing natural and social systems through the blockchain.

The recent NFT boom, largely driven by crypto-entrepreneurs, uses NFTs mostly as sales mechanism rather than medium. It also reduced the public image of digital art, which covers a broad range of creative expression, to individual reproducible digital images, animated Gifs or video clips — the standard forms of digital collectibles and meme culture.

At the same time, there are artists and platforms that explore the generative potential of the blockchain and comment on how NFTs have commodified the sales mechanism itself. Artist Jonas Lund’s participatory NFT artwork MVP (Most Valuable Painting), 2022, comprises 512 digital images and, once one of them is minted and sold, its properties determine the evolution of the remaining ones through fitness and other algorithms. John F. Simon Jr.’s NFT version of Every Icon (2021) set in motion a generative process, with the code stored on the blockchain. Platforms such as artist Casey Reas’ Feral File, which brings together artists and curators to establish transparent protocols for exhibiting and collecting file-based art; art blocks, featuring programmable on-demand generative content stored on the blockchain; or e∙a∙t∙}works, which builds on the history of art and technology to experiment with new forms of engagement in the NFT landscape, all propose valuable models for counterbalancing the purely commercially oriented marketplaces.

What other changes do you foresee in the structure of the art system following this economic ‘crypto-bubble’, if we can call it that?

The NFT gold rush has been investment-driven, with the art world following the economy rather than the other way around. The art system has to acknowledge digital art’s rich history and its potential for creatively exploring the crypto space and decentralized distribution. The blockchain also has wider implications for the Web, its communities, and its infrastructure. Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs), communities owned and controlled by members according to transparent rules and transaction records maintained on the blockchain, have recently gained more traction in the cultural sector. DAOs potentially can organize cultural creators — with the goal of fostering creative agency in a collectively owned space — and tokenize, archive, and collect their creative output. It remains to be seen whether Web3 as a new iteration of the World Wide Web based on blockchain technology and existing as a decentralized space with token-based economics will catch on, but the crypto bubble has definitely led the art world to rethink and explore new models of selling (whether its artworks or tickets), collecting, fundraising, and membership building. My hope is that the crypto bubble will burst enough to give the art world space for focusing on more beneficial, conceptual, environmentally sustainable models for art production and experience, as well as community building.

In an interview with Ben Fino-Radin for the podcast Art and Obsolescence (November 30, 2021) you said that serious collectors are not that interested in NFTs as they can acquire a major installation for the same price. Has anything changed since then? Do you think some serious work has emerged in this area so far?

My comment wasn’t meant to suggest that artists weren’t doing serious work in the NFT landscape. As mentioned before, artists have been doing very interesting projects on the blockchain over the past decade, and these works definitely would be of interest to collectors. My statement referred to the common practice of creating NFT “spin-offs” from existing works. Artists and gallerists entering the NFT landscape now often mint NFTs for stills or brief clips from complex and interactive digital artworks to adapt them to the market’s constraints. Since the NFT market is hot, the original works can sometimes cost less than their excerpted versions sold as NFTs. To devoted collectors who have been following and acquiring digital art for decades, the NFT is consequently much less interesting than the piece from which it derives. Museums and traditional collectors are not striving to make quick money but look for creative work that uses digital technologies as a medium. Collecting jpegs per se is not a main attraction for them.

In an interview with Maria Efimova (Art, August 2021) you mention how important the archive is. What other sources and creative forces could you envisage as partners alongside archives – Artbase and Net Art Anthology at Rhizome or Archive of Digital Art, for example – in order to shed light on the nature and the history of digital art for a broader public?

Archiving and documentation are important parts of constructing histories and preserving art, thereby making it more understandable to audiences. Other crucial factors in making digital art more accessible to the public at large are presentation and collection. There still aren’t enough exhibitions of digital art mounted at institutions around the world, particularly when it comes to more historical ones that build connections to other art forms. Digital art remains a bit of an outlier in museums, galleries, and at art fairs and is too often presented as a trendy novelty. Its accessibility to a broader audience also depends on institutions’ commitment to collecting and preserving the art form and ensuring that the public can experience it in its original form rather than as archived documentation.

Besides being a curator, you are also a professor. What impact does teaching have on your work and research? What major changes have you identified in the younger generation of artists and students over the last five years? What have you learnt from them?

My positions as curator and professor constantly inform each other. My curatorial practice shapes my teaching, allowing me to draw from my experience in exhibition making and provide insight into institutional structures; my teaching and academic study allow me to deepen my thinking about media and question my curatorial research. I have always learnt a lot from my students, they are an invaluable resource since they have a different conceptual framework for getting a perspective on the world and the position of art. Obviously they tend to be particularly interested in the more recent technological trends — whether that’s the new wave of virtual reality or AI art or augmented reality — but I have also noted more conceptual changes. The boundaries between the physical and virtual, or between the original and copy seem to have become increasingly blurry for them and that also influences how they understand value. Experience seems to be more important to them than uniqueness.

images (cover 1) Jonas Lund, «MVP (Most Valuable Painting)», 2022, commissioned by Aorist, screenshot (2) Christiane Paul, portrait, ph: Lacombe (3) American Artist, «Looted», 2022, screen shot, Courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art