Observing Japan through the eyes of a westerner inevitably results in an experience that is rich and astonishing. It is even more intense if mediated by an intercultural approach. The way geishas and microprocessors manage to stand side by side in everyone’s mind demonstrate the ambivalence of Japanese culture. Such ambivalence has become an emblem of the historical changes that occurred in a country which, after having been exposed to western culture, was capable of embracing the positive aspects of their progress – assimilating them into the fine arts, architecture and technological research to the point of developing into a great world economic power. Many of these cultural dynamics are discussed in L’epopea dei robot / The Robot Epic, an essay by Marcello Ghilardi.

There is no avoiding contradictions, however, when analysing the culture of a nation with thousands of years of history that is hyper-contemporary at the same time. Artists like Araki and Murakami, between indiscretions in kimono and a superflat philosophy, are today’s spokespeople of these discoveries. Japanese society in its entirety is the object of profound artistic reflection – as are the incoherencies of progress, issues linked to capitalism and the toll required by modernization on a collective psychological level and in terms of environmental impact.

The robot and humanoid epics featured in anime and manga animations – broadcasted for the first time in Italy in the 1970s are a perfect example of this matter. The imagination of entire generations was marked by heroes who left an indelible impression on our collective memory with their samurai-styled costumes, gestures and weapons. The distinguishing factor of their adventures was the battle to defend humanity and its natural environment coupled with a journey of self-discovery. At the time, Japan saw itself and its society in a different way. It felt the weight of change and created a new generation of humans: the adolescents who were protagonists of manga and anime were humanoid warriors or extraordinary robots who were also outcasts of their own society.

The concept of wabi-sabi must be introduced in order for westerners to read the arts of manga and anime and their natural and artificially blended dialectics. This concept is a central poetic element found throughout Japanese culture – permeated by violence, sex, infantilism, apocalyptic catastrophe, hyper-modernism, reigning traditionalism and its influence – that represents a sense of restlessness along with the beauty found in decadence and the precariousness of life: the fragile cherry blossom blown about by the wind is the most common and representational image of this notion.

The Japanese anime set on a science-fiction backdrop clearly reveal this philosophy as their characters move about in a context that is futuristic, utopian, contradictory and transformational. The society in evolution projects itself forward while perceiving the disturbing effect of change; robots and humanoids maintain the depth of their sentiments underneath their mechanical shells – the conflict between technology and contemplation, past and future – as they materialize the dramatic tension between body and spirit through fantastic imagery.

The anxiety of an entire population takes shape here (2): a population that has been historically traumatized by atomic bombs and natural disasters must make their way to the future nonetheless.

The sagas of the robots change for the new millennium (3) and sabi is replaced by cyber. Metaphorically speaking, the cyber culture of the latest anime and manga – so familiar to the young popular set – translates the overcoming of physical limitations through progress, an expansion of physical and psychological boundaries, meditation upon the concepts of virtual reality and identity, the development of technological means and the increasingly urgent need to reflect upon their purpose and cost.

This text was inspired by the essay by Marcello Ghilardi L’epopea dei robot, in «Culture del giappone contemporaneo. Manga, anime, videogiochi, arti visive, cinema, letteratura, teatro, architettura», curate by Matteo Casari, Tunue’ Editori dell’immaginario, Latina, Italy 2010 (Italian).

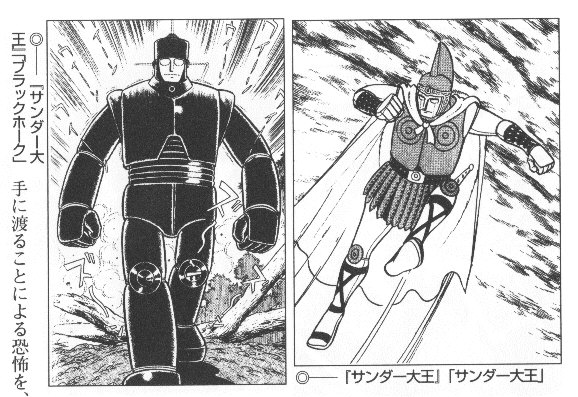

Images (1 cover) Devilman – by Go Nagai (still-frame); (2) Chouju thief, 1200s; (3) Thunder Daiou e il suo avversario Black Hawk; (4) La città incantata, Hayao Miyazaki (still-frame), 2009.