In conversation with Dobrila Denegri, artist Vesko Gagović talks about his intervention at the 58a Venice Biennale for the Pavillon of Montenegro. His project Odiseja unfolds from the film “2001: Space Odyssey” and it alludes to the way technology and science interwave in the day to day life and in the imaginary of the future.

Dobrila Denegri: Certain products of human creativity have the power to form, influence and inspire entire generations. Music has this cohesive effect, as proven by examples of rock classics such as Pink Floyd’s “The Dark Side of the Moon” or Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven”. Same goes for certain pieces of literature or cinematography, among which “2001: A Space Odyssey” holds a special place, both as Stanley Kubrick’s film and Arthur C. Clarke’s novel. The way in which the issue of civilizational evolution through technologic progress is addressed in “2001: A Space Odyssey” still resonates strongly today. Advancing with increasing speed, technology profoundly informs our sense of reality. In addition, the hyper production and the hyper consumption of information and visual data makes us feel as if we were immersed in something like a “permanent nowness”. By the time we manage to elaborate, contextualize, and question the meaning of these contents, they have already become obsolete, they have become “history”. What triggered you to reach out for such a historical and multi-layered reference such as “2001: A Space Odyssey”?

Vesko Gagović: My impression is that the theme “May You Live In Interesting Times” concludes a circle of considerations which were expressed through the last several editions of the Venice Biennial, and which assert that we are now in the moment of total saturation that calls for a big gesture of responsibility towards the world and towards a different way of living on the planet. We can either re-propose old schemes or start from scratch, re-imagining the relation between present and future. We need a new modus vivendi! Thus, the reference to Kubrick is not accidental, because the film treats the topic of civilizational evolution through technological progress, it speaks about the end and the beginning, and anticipates the possibility of a non-human intelligence and its impacts on the life on Earth.

In order to fully understand your work, it is very important to grasp your referential points, which are often presented in allusive, subtle and indirect ways. Your abstract and formally reductive language does not immediately reveal references other than the purely pictorial ones. But despite the importance of formal aspects, a set of elements that appear as a “sub-text” seems equally relevant, given that it provides your work with the character of social commentary which can be reflexive, critical or ironic. For example, the series of paintings/objects from 2000 (black, silver, gold) cannot be fully understood without realizing that their titles correspond to the colours of cars considered to be status-symbols for certain social strata in Montenegro. The title of the series “Rags” from the late 1990s, seems to suggest that there is much more to them than just painterly considerations of questions of colour, composition, structure, etc. How do you see the position of the artist in the context you live in?

Openness, boundaries’ shifting, information flow, technological acceleration, alienation, anxiousness, hedonism, pain… we live all this things. We live in interesting times indeed… We live in a time when interest in art is much smaller compared to the attention given to science and technology. Science itself is increasingly becoming a bigger part of artistic research, or according to Damien Hirst, it is becoming the “new religion” for many. Ours are also times of spectacularization, which aims to make everything more immediate and more communicative. For an artist now is impossible to withdraw and work in a studio removed from everything. An artist has to operate like a producer, director, curator. If widely affirmed, an artist has to have entire teams of people working on the production and promotion. But regardless all this, I believe that, first and foremost, an artist today has to have an own voice and take an active and engaged part in the current social discussion. When I look over my entire production, I realise that beyond the formal aspects, which are indeed important for me, there is always certain narrative layer which refers to our local traditions or expresses my critical comments or intimate states of mind.

From the early abstractions to the later monochromes and reductive and “colour filed” painting, the art of the 20th century claimed its right to linguistic autonomy. Art didn’t have to represent anything else but itself. In the 1980s though, with artists such as Peter Halley and others, a type of painting practice emerged that laid attention to surface, geometric forms and the applications of colour, in order to address questions related to the logic of technocratic and capitalist systems. You also started with your artistic work in the late 1980s. How did you introduce geometric, reduced, abstract forms in your work?

Geometric forms stared to appear in my work in the early 1990s, when we were living under the pressure of war and the deep crisis that followed the disintegration of Yugoslavia. In this profoundly tragic and tormented period, as an artist, I felt the need to affirm the ideal of composure, concentration, and autonomy of art. So, instead of rough ones, I started using delicate, fragile materials, such as wood, glass, industrial grey colour, tapes, chisel… I would intervene only minimally on the surface of the glass: with a layer of colour (grey) and a simple geometric shape (triangle or circle, outlined though the alternation of vertical thin lines), I would create discreetly geometrical, almost pop-art objects. For me, they were miniatures, boxes, just objects I made following an intimate inner feeling.

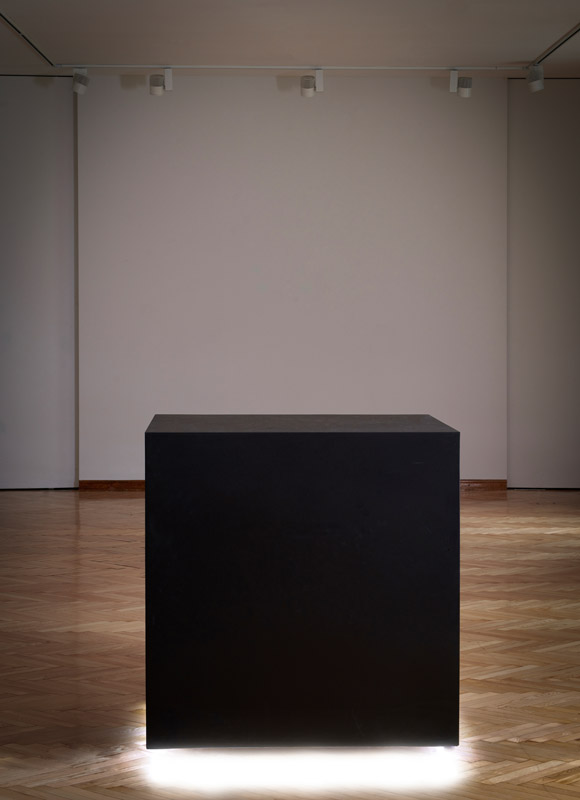

DD: Your “Suspended Objects” raise associations to the Monolith from Kubrick’s “Odyssey”. It may be interesting here to recall another artist whose work triggered similar associations: Alan Charlton, the “painter of grey paintings” as he used to define himself. He aimed to create art which would be “abstract, direct, urban, basic, modest, pure, simple, silent, honest, absolute.” Do you recognise yourself in similar aspirations?

I always work with a single concept in all my productions. On the one hand, this concept relies on a tight link between minimal intervention, concision, monochromy, pure forms, rigid abstract structures. My paintings/objects are expression of the unity of this elements. On the other hand, there is always a clear mental dimension. The meaning of the work derives from the method of the treatment of materials, from pictorial process itself, and the study of the space and the surrounding context.

There is this iconic scene, not just for Kubrick’s film, but for the history of cinematography in general, when the Monolith appears in the landscape which looks like “the beginning of times”, inhabited by those who might well be our ancestors. The scene goes towards its crescendo when the ape takes the bone and start using it as a weapon or an utensil. The epic tones of Strauss’s symphonic poem entitled like Nietzsche’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra”, emphasises the symbolic importance of this gesture, which represents a crucial step in the evolutionary process. As Kubrick’s film alludes, and Arthur C. Clarke confirms in his novels, the Monolith is of alien origins, and represents as such a form of superior non-human intelligence. In Clarke’s saga, monoliths appear several times, always to indicate higher states of consciousness or salvific drives towards the human kind. There are many interpretations of the “Space Odyssey”, but if we would transpose some of its aspects to the current moment, paradoxes of our times might emerge. On the one hand, science and technology, fostered so strongly today, represent an inclination towards elevation, while on the other, the dominant political narratives exploit the lowest human impulses in order to gain large consensus. Does this theme of the dynamics between progressive and regressive inclinations have any resonance in your work?

Certain works within my production do relate to the social, political, and cultural context in which I live and work, because naturally, as any other artist, I cannot live isolated in an “ivory tower”, but must be fully immersed in the concrete reality which I observe and reflect upon. Works like “Hygiene” (video), “Audi” and “Mercedes” (paintings/objects) and “Adriatic Sea” (installation), are the ones that convey more directly this critical dimension.

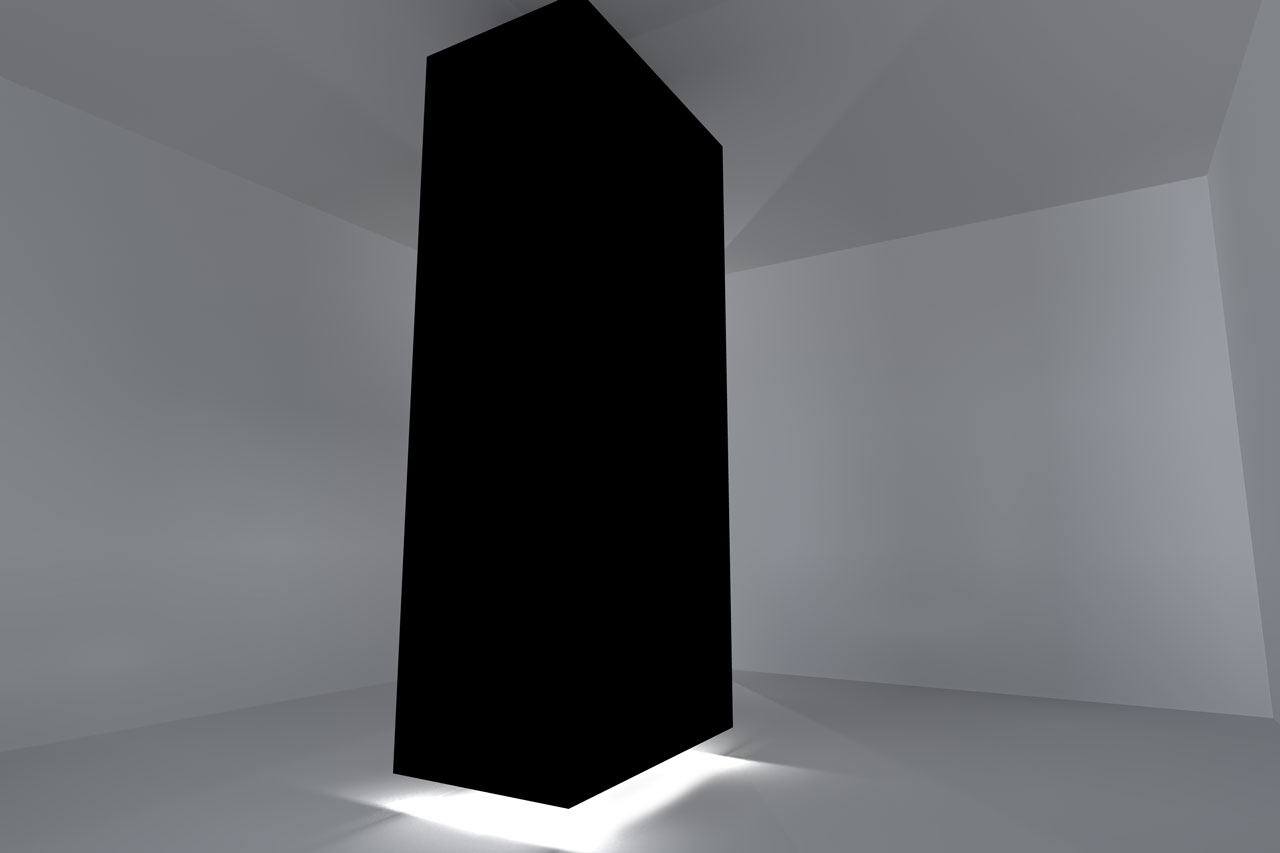

Now, taking as the point of departure such a strongly charged symbol, I realise a series of objects which “float” in space. This objects, inspired by the Monolith, are perfectly realised. Through them I objectivise visions of a far future, a hypothetic imaginary time of a reality constructed in a better way. Here I also mix elements of humour, science fiction and cultural emancipation.

“Floating Objects” might appear hermetic and imposing. Their enigmatic look might trigger whole range of reactions, which go from attraction to disinterest. They stand on the thin line between reality and illusiveness. Their massive spatial volume is laid on the “plinth” of light: a material object is “carried” by something immaterial. Can you comment on this dialectic of material/immaterial that the work emanates?

The piece entitled “Floating Object MDF” (200x200x60 cm, gold metallic colour, MDF, LED) was exhibited for the first time in the Petrović Palace gallery in Podgorica in 2014. Now, for the presentation at the Pavilion of Montenegro, it is slightly modified to fit the space and context of my project at the Venice Biennial.

The original structure of this work was a case used to transport my paintings “A8” and “A180” shown at the exhibition “Adriatico – Le due sponde / 52th Michetti Prize” at Francavilla a Mare in 2001. This case was modified, losing its utilitarian function and becoming a perfectly levigated and proportional vertical structure. Empty inside, it is installed in a way so as “not to touch” the ground, and a strong light emanates from its base.

The “Odyssey” project is composed of three large 3D objects in different sizes and shapes. They are positioned inside the three rooms so as to give an impression that they are hovering. They are realised in situ, by mounting wooden and plaster structures, which are then painted with great number of layers of colour.

The first object “Cube” (100x100x100 cm) stands in the centre of a rectangular room, and it is matte black. The second, “Floating Object” is a big 3D parallelepiped which develops vertically reaching towards the ceiling, painted a shiny gold. The third, “Monolith” (230x150x50 cm) is a high vertical rectangle painted matte black. From the base of all three pieces, a strong LED light emanates which, reflected on the floor, gives the impression of the object’s “suspension”.

Each “Floating Object” has a purely geometric form, occupying the space centrally as if asking the viewer to walk around it. This aspect recalls certain works done previously by artists who were interested in the notions of geometry and perfection. I could mention, for example, “The Table of Perfect” (1989) by James Lee Byars – a perfectly proportioned marble cube with rounded corners and edges, and covered with golden leaves. In line with Byers’ poetics, this sculpture has at the same time both a votive and a speculative character, which addresses the notion of perfection which must always remain, for us, in the realm of the unreachable. Another example which comes to mind is Malevich, who after his “Black Square” planned to create a black cube that was supposed to be Lenin’s grave. Even if initially not conceived as a homage to Malevich, a similar work was created by Gregor Schneider in Hamburg and New York (2007), after failed attempts to place his black cube in Berlin and at the St. Marco square in Venice. His primary motive was Kaaba in Mecca, and its religious significance. Even though these examples do not share the same references and interpretations as your work, there is something in common with each of them, namely the relation which a sculptural object establishes with the viewer. The impermeability of the geometric form forces the spectator to walk around it, in an almost ritualistic or performative manner. Are you interested in the performativity of the sculpture/observer relation?

I believe that the secret of every idea is in its mysticism. When something is revealed, when there is an understanding on why “something is as it is”, the myth is gone. That is Kubrick’s message, too. Even if these works are pure geometry, totally minimal, simple, reduced, their positioning in the space and their strong visual impact might trigger reflections and open a wide spectrum of potential associations and interpretations.

“Floating Objects” will not only have a myriad of effects on the audience, but they will be important for me to better understand what happens between the work and the viewer in the space. The meaning of any artwork operates on the rational level, but it also goes far beyond rationality. It might be especially interesting to see how these severe geometrical, minimal objects which associate to Kubrick’s “Odyssey” will function when read in the frame of the main theme of the Biennial “May You Live In Interesting Times”, proposed by its artistic director Ralph Rugoff.

How will the placement of “Floating Objects” function in the space of Palazzo Malipiero, the location of the Montenegrin Pavilion in Venice?

The spaces of the pavilion fully correspond to the idea of ambient display and the establishment of direct communication with the audience. The dimensions of each object are in proportional relation to the sizes of each room containing them. Three objects are positioned centrally so that the audience can move circularly around them. In this installation, what interests me is the qualitative relation between minimal construction, its volume and the hypothetic suspension in the space. These objects, which emanate a strong light from bellow, create an illusory effect which affects the entire gallery space, shifting the gravity field in a direct relation with their surroundings.

image

(cover 1) Vesko Gagović – “Odyssey / Cube” – render (2-4)Vesko Gagović – “Odyssey / Cube”, 100x100x100 cm. plaster, MDF, LED, black matt colour. Photo by: Duško Miljanić (3) Vesko Gagović – Portrait. Photo by: Duško Miljanić