2014 was an annus mirabilis for Teho Teardo: for both his live and studio productions, for the number of projects he successfully completed and for the ideas he brought to fruition, for the consolidation of pre-existing collaborations and for his new encounters. Fifty sold-out live performances throughout Europe (with Blixa Bargeld and with his “Music for Wilder Man” project) and the gratifying theatrical experience with Enda Walsh with Ballyturk, whose musical score has just earned him a nomination at the Irish Theatre Awards for sound design.

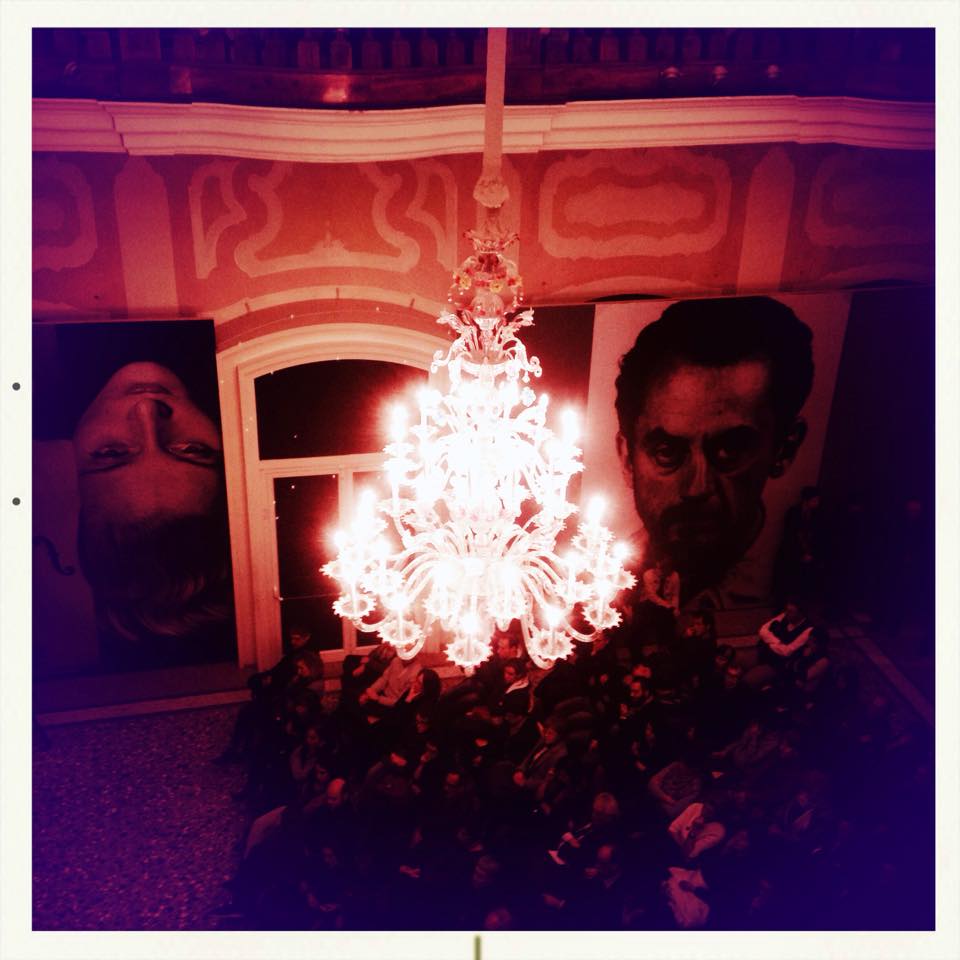

Unstoppable is also his work as musician in the world of filmmaking which seen him scoring some films of Man Ray. After the world premier at Villa Manin (Udine, Italy) the music for three films by the Dada artist as a part of a large exhibition dedicated to him, Teardo is bringing his project to Italy’s largest cities beginning with Turin, Rome and Perugia. Elena de Stabile is featured on the violin, Stefano Azzolina on the viola and a kind of installation of forty electric guitarists will join Teadro himself on stage for the finale.

Susanna Buffa: Judging by the enthusiasm with which you embraced Man Ray’s film work, we can grasp what an important figure he is to you. Man Ray was always changing his stride – from illustrator to graphic designer, then publicist, photographer, painter, director and sculptor. You often change directions as well.

Teho Teardo: Yes, I do. This is in part due to my belief that if you stick to the same things for too long you lose objectivity. Music often calls for a change of position in order to be inspired and to compose. I work on several projects simultaneously and I often need to observe the same thing from different points of view.

Was the choice to score these three films by Man Ray yours?

Man Ray made four films. Piero Colussi (superintendent of Villa Manin, curator of the Man Ray project and exhibition. Editor’s Note.) suggested these three: Le retour à la raison, Emak Bakia and Etoile de mer. I agreed that these seemed to offer a fascinating venue in regards to music.

If you were requested to do so, would you score the fourth film as well?

Immediately. Actually, it had crossed my mind but this particular project has its own definitive form. I might decide to replace one of these three films with the fourth one at some point in the future.

As a young artist, Man Ray built some strange and bizarre objects that were seemingly useless. They did have some meaning for him, however. You, too, make and use strange objects to create sound.

I do make strange use of objects. That could be something we share. I use the electric drums to create drones and atmosphere sounds. I use compressed air, technology for unusual purposes. I also use pruning hooks, scissors and electric currents for the static sounds and interference they produce. I use damaged, faulty hard disks…I feel connected to Man Ray in this way. When I think of him, I can’t help but think of Duchamp as well. There are affinities there and the shared belief in ready-made – giving objects value (aesthetic value or merely by using them) that had never been considered before that time. When you start to use the disruption caused by a mobile phone in your rhythmic sources, that means you’re getting closer to the idea.

Dadaism knocked down the barriers between theory and practice: an effective way to escape from a system of rules and conventions, a kind of rebellion. Is there any rebellion in today’s music?

I think rebellion is expressed through the dissent against the way things are going and it is justified when it finds its own point of view of the world. I don’t want to accept the world as it appears. I think there is a possibility of making it a better place. Music doesn’t change the world, but the people who make music can find a point of contact with those listening to it in order to make us more aware of where we are and who we are.

When I approached the world of Dadaism, I was surprised by the movement’s ability to be so provocative. The element of aggravation and challenge in the figurative work of the Surrealists and the Dadaists before them was more distinct, more evident and even more dangerous in comparison with the music that was being composed at the time. That sense of danger, that tendency to call everything into question, has always intrigued me. It also revealed humility. I believe that Man Ray conveyed a great message of humility.

Man Ray believed in the possibilities that an encounter had to offer – his encounter with Duchamp is emblematic, but there were many others as well. I don’t want to wrench a parallel between you and him but it is obvious that you seek out exchanges and collaborations with other artists.

I have always done that. At first, it was a reflection of something I was lacking and it was motivated by the fact that I lived in Pordenone, a tiny city that was so far from the musical world that interested me. This is why I have always sought out encounters, written to and tried to get into contact with the people I was interested in communicating with. Besides, being alone is boring. It’s like always swimming in the same aquarium. You need to get out of there.

Did you have the sound you wanted in mind as soon as you were invited to work on the Man Ray films?

No, not all. I had to ponder it for quite a while and in a way that was rather «situationist». I thought «OK, when I get back to my studio I’ll start working with just the objects on my table». I had a bell, two knives, pruning hooks; a pair of scissors…blunt instruments, sharp and potentially dangerous. And I got a kick out of this coincidence. Then I added some others but everything happened by just using these things on my table. I wanted to give myself some limits and make my way through an enclosed area. When you give yourself some rules and are forced to work with what little you have, you really have to face the challenge. In the middle of this rather rhythmic beginning, I tried to include some harmonic and melodic elements: there are a lot of strings (violins and violas are kind of obsession at the moment) and guitars. Percussion is very strong, too. It’s no coincidence that the first sound I recorded for this project is a bell and the first film, Le retour à la raison, begins with a bell.

Your approach changed for this film: you usually work on the scripts and not on filmed material. In this case, your work was based upon final cut images and editing.

Yes, this was very new to me. I normally prefer to work with the script and imagine a world that starts from there. Everything was different this time. Having seen the films, it is most likely that there was no script at all. There was also no director to work with. Man Ray died in 1976. I was only ten years old at the time so there is also a temporal distance between us. He told of another era. I must admit that my curiosity about that period doesn’t derive as much from the time lapse as much as it does from the fact that the era has been deleted. Whenever I think of a fiercely identifiable Europe, the 1920s and 30s come to mind (and not with nostalgia). The art being produced during that era was very precise and expressed Europe exactly as it was. Those artists had begun to delineate a very significant European identity that was wiped out by World War II. It was not possible to recover that identity because Europe was invaded by American culture, art and music immediately after the conflict.

I think that artists have the task of deciphering their era, to systemize and tell of their world: The film work of Man Ray and his contemporaries brought hope for a fantastic future. The strong sense of joy and energy found in their work was all swept away by the war and there is no going back. Because that would mean a nostalgic output – which was the extreme opposite of Man Ray’s artistic quest.

You are an artist, too. How are you interpreting the present and how do you see the future?

I think that one of the filters I use to see the world is a kind of restlessness that stretches all the way to utopia.

While listening to your music, we can perceive that you worked in a condition of extreme freedom. This is also true because you know the artist and his world so well.

Exactly. I wrote an imaginary letter to Man Ray telling him that I didn’t like the idea of a soundtrack because it presupposes an «accompaniment». An art film needs no accompaniment. What is needed here is to establish a relationship with it. If I had composed music as a comment to his films, I would have feared a raid from Man Ray in the middle of the night and he would have split my skull open with his famous tack-lined iron.

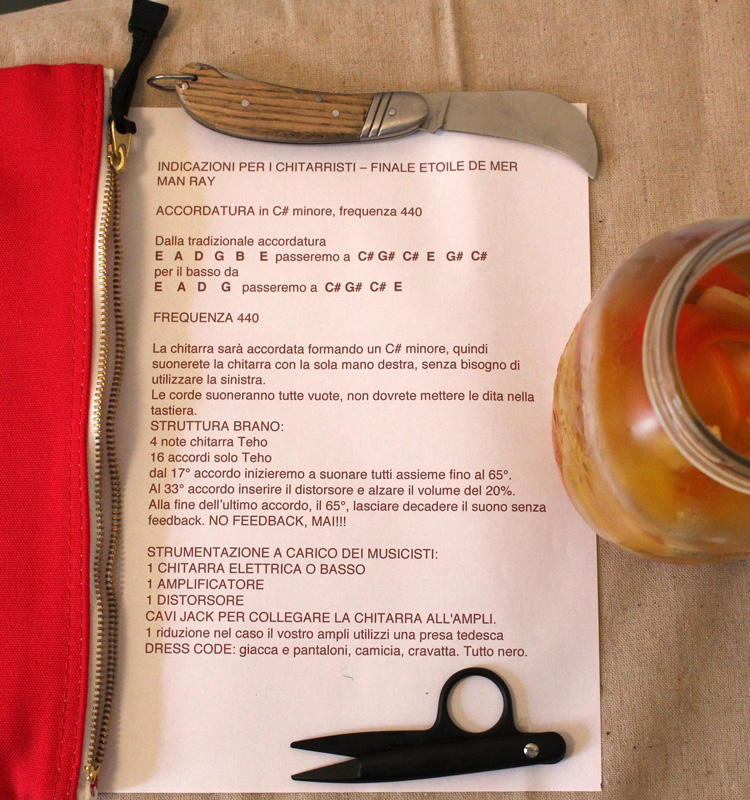

Live performances of the music for these films close with a kind of installation with forty guitarists, all of whom have amps and distorters. What inspired this idea?

After the fade-out in the last film, forty guitarists start playing a single chord with me for about 15 minutes; it’s an ambiance that is almost sufi due to the reiteration and repetition. Man Ray told of a world, as I mentioned earlier, that was obliterated by the war. There is a bell tolling the funeral of the broken and interrupted 20th century. He appeared to me in a dream repeating this number: «Forty!». I didn’t understand right away what that could mean but then I came up with the idea of finding forty guitarists and placing them within the final piece in real Dada style. So, from the screening of the last film and to a live performance with forty guitars: it is a transition to pure concert music but there is still an echo in the air of that world which no longer exists.

Teho Teardo, La retour à la raison: Musique pour trois films de Man Ray, February 7, 2015: MAXXI Museum, Rome – February 24, 2015, Postmodernissimo di Perugia/ this interview appeared on the Italian online art magazine Exibart, on February the 2nd, 2015

images (cover) Teho Teardo, Le Retour Raison, © Elia Falaschi (1) De Stabile, Teardo, Azzolina, © David Wilson (2) Teho Teardo, Villa Manin, © Susanna Buffa (3) Teho Teardo, Villa Manin, © Elena Tubaro (4) Teho Teardo, Villa Manin, © Elena Tubaro (5) TehoTeardo, Le Retour Raison, © Elia Falaschi (6) Instructions for guitarists.