Technology has found its way into every field of knowledge and action. In some cases, it has become a vehicle of power and consumption and in others it has been adopted to implementing quality. This happened in the world of dance, a sector in which technological potential has acted as a stimulus for choreographers and performers since the 1970s.

«The introduction of technological devices to the stage, from video to motion capture, has redefined the perception of the body and the composition of movement». This is the incipit with which Prof. Enrico Pitozzi introduced his public lecture at the MAXXI Museum in Rome (February 8, 2014), Choreographies of technological devices, within «Histories of Contemporary Dance», curated by Anna Lea Antonini.

The fusion and relationship between technology, dance and mind, as a dynamic capable of increasing awareness of body perception is at the basis of any kind of choreographic evolution and revolution, in the sketching of any single movement as well as its interaction with the entire stage. The multiple interdisciplinary elements of the lecture revolve around this theme. Interaction between technology and imagination with the resulting involvement of other scientific disciplines like neurophysiology is, thus, the leitmotif that guided the talk, even when it delves into a more specific analysis of software like Life Forms, Motion Capture and Isadora, considered here as «forms of thought».

The possibility of an external view of things, the ability to intervene upon our avatars – to position it and have it interact with the computer-reproduced space are some of the functions of the Life Forms programme whose every potential was anticipated by visionary choreographer Merce Cunningham. It is from an external analysis of motion through Life Forms means, that his implemented knowledge and consciousness of his own body enabled him to experiment a more coherent involvement of the arms, which had been used exclusively for balance purposes until that moment.

Life Forms, in use since the late 1980s, allow for an objective view of things and make it a simultaneous intervention possible in a single movement and in its interaction with choreographic elements on stage. Alongside of this, developed at a later moment, there is a system of motion capture which makes it possible to visualize the body «from» and «in» motion. Sensors applied on dancers capture movements and transmit them to specific software that converts them into a dynamic drawing; the presence of the dancer is completed by the perception of those watching with empathetic means. Then, when the body in motion can be reproduced on stage at a later date, dancers and choreography interact in a reciprocal exchange.

Pitozzi teaches us how scientific progress (with his increasingly sophisticated ability to see through things and capture them in the smallest forms in which the universe is manifested) stimulates the desire to obtain the invisible. That same impulse drove scientist and physiologist Étienne-Jules Marey (1830-1904) to study the chronographic process – in Pitozzi’s opinion, a clear antecedent to motion capture.

A series of examples of choreographic productions created in the technological dimension come to mind, from Merce Cunningham and William Forsythe to Wayne McGregor and Ginette Laurin, in order to reconstruct the history of research expressed by a desire to go beyond things or – more specifically – to succeed in seeing them in their very existence and interaction «in matter». That which is invisible is revealed in its material presence. Motion is body and matter as much as digital in that an interface (as indicated by the term used in Physics) is the moment of transformation from one state to another. In more recent experiments the body can disappear completely to leave the stage to a volume of air occupied by a motion that becomes a «dance of particles».

And so, this is how everything returns to matter: through its visible and invisible being, in its existing inside and outside things, in its manifesting through the game of full and empty; understanding this all is found in the hidden potential of the mind that technology is capable of either keeping in a state of drowsiness or stimulating to the very limits of what is possible. This is the reason why this specific theme treated in such a transversal manner reaches beyond the discipline of dance and can be expanded to all other disciplines where they flow into life, and into the power of the mind – a power freed by imagination through anything can stimulate it, possibly technological devices.

Enrico Pitozzi teaches «forms of the multimedia scene at the Department of Arts at the University of Bologna. He was visiting Prfessor at the Faculté des Ars de L’Unversité du Québec à Montréal and visiting lecturer at Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris III within the European program Teaching Staff Training 2013. Among his writings, he is author of Corpografie. Percezione, presenza, dispositivi tecnologici (Perception, presence, technological devices), in M. Borgherini, E. Garbin, Modelli dell’essere. Impronte di corpi, luoghi, architetture, Venezia, Marisilio, 2011. His monographic work, Sismografie delle presenza. Corpo, scena, dispositivi tecnologici is about to be published with Casa Uscher Editor, Florence (Autumn 2014).

The lecture Coreografie e dispositivi tecnologici/Choreography and Technological Devices, took place in the MAXXI’s auditorium, Saturday, February 11, 2014 within Histories of Contemporary Art, a project devoted to the fostering of dance history by Carolina Italiano, curated by Anna Lea Antonlini, and organized by Giulia Pedace. Next lectures: 8.03.2014: Danza, Paesaggi, Ecosistemi/Dance, Landscapes, Ecosystems (1990 – 2013) with Fabio Acca, and 12.04.2014, La Danza tra memoria, documentazione e video danza. Viaggio nell’archivio Cro.me/Dance between memory, documentation and video dance. A journey into the Cro.me Archive, with Enrico Coffetti and Francesca Pedroni. MAXXI – National Museum of the Arts of the XXIst Century, Via Guido Reni, 4A, Rome

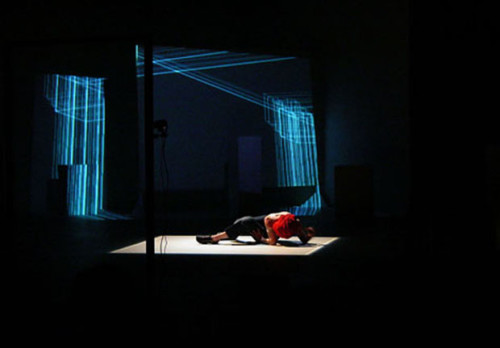

Images

(homepage cover) Still from digital projection by Shelley Eshkar and Paul Kaiser for Merce Cunningham’s Biped, 1999. Courtesy of OpenEndedGroup; (1) William Forsythe, Improvisation technologies, 1999-2003. Photocredits: Forsythe Company; (2) kondition pluriel, schème II, 2002, Photos: Martin Kusch. Courtesy kondition pluriel; (3) Dumb Type, Voyage, 2002, photos by Kazuo Fukunaga. Courtesy Epidemic.