< Interviews

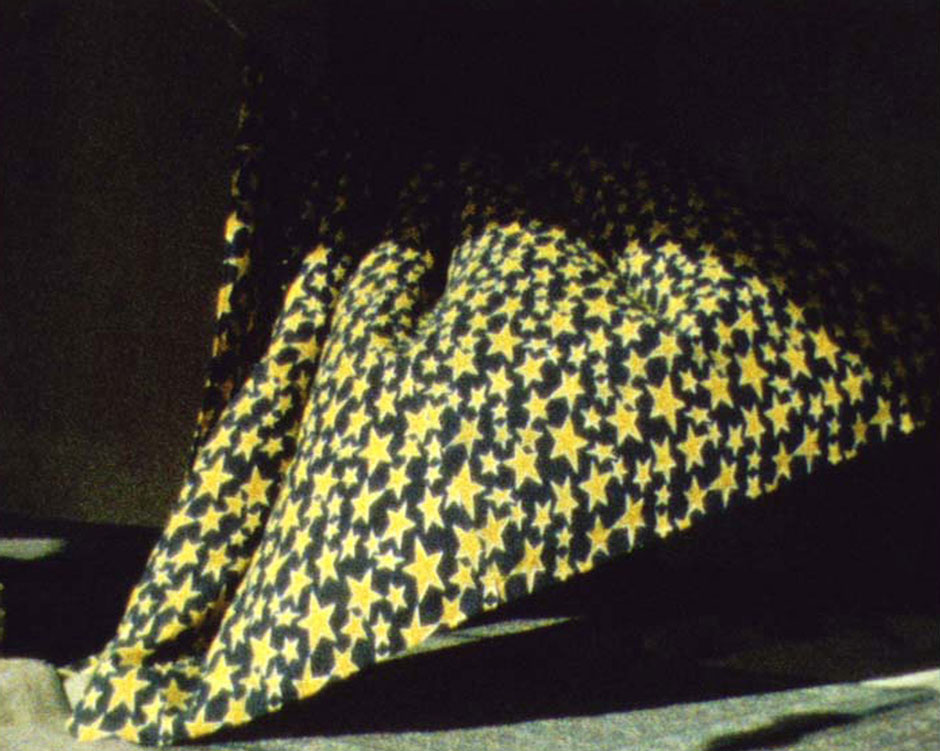

Anna Franceschini, You must believe it to see it (Le Tempestaire), film, color – mute, 2012, still from video, Premio Terna 04 (category Gigawatt)

Anna Franceschini was born in Pavia in 1979. She currently lives and works in Rome, Brussels and Milan, the city where she studied, earning a Master’s degree in Television, Film and Multimedia Production (IULM) and then a postgraduate fellowship in the History and Criticism of Italian Cinema. The artistic work by Anna Franceschini is based on the exploration of reality, seen through the relationships that develop between people, places and objects and which animate them. She uses a variety of tools with an emphasis on film and video as tools that enable people to experience emotional passages and their subsequent impact on things. The human figure is almost never present unless viewed through the life of the objects. Since 2010 she has worked mainly in Super 8 and 16mm, «I like the relationship one has with the film stock when it is turning,» says Franceschini, «it creates a tension, because any waste (money, time, opportunities) is drastic, so one has to pay closer attention. There is actually a chemical-physical transformation of matter, and that’s interesting.» Several works by the artist have been selected and awarded prizes at prestigious film festivals including the 60th Locarno Film Festival (Switzerland), the TFF/Turin Film Festival (2008), the MFF/Milano Film Festival (2012) and the Rotterdam Film Festival (2015). Her work has been featured in numerous galleries and institutions in Italy and abroad. These include: MARCO (Vigo, Spain, 2014); MAXXI Museum (Rome, 2014); MNAC (Lisbon, 2014); MACRO (Rome, 2014); Elisa Platteau Gallery (Brussels, 2014); Jeanine Hofland Contemporary Art (Amsterdam, 2013); Italian Cultural Institute (Paris, 2013); Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa (Venice, 2013); Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo (Turin, 2013); Museo Villa Croce (Genoa, 2012) and Palazzo Reale (Milan, 2011).

In 2011 she received a special mention in the Ariane de Rothschild award (Milan). In addition to the Terna Prize in 2012, she was the winner of the Fondazione Casoli Prize (Fabriano), the New York Award – Ministry of Foreign Affairs (IT) and the MACRO Amici Prize (Rome). She has been granted several residencies: Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten (Amsterdam 2009-10); Castello Malaspina / Residence for Visual Artists (Fosdinovo, 2011), Kunsthuis Syb (Beetsterzwaag, 2011); Via Farini (Milan 2011); ISCP (New York, 2012-2013) and MACRO Museum (Rome, 2014). Her productions have been supported by a number of grants: Nicoletta Fiorucci Art Trust Fellowship – Italy (2011); KPN Fellowship (2010); Associazione GAI / Ministry of Heritage and Cultural Activities/ Movin’up (2008).

You must believe it to see it (Le Tempestaire), the work which was among the winners of the Terna Prize 04 in the Gigawatt category, is a 16mm film presented on an Eiki projector. The film captures what goes on inside a glass case which contains a music box topped with an automatic mechanism that represents a sailboat in the middle of a storm.«“My work,» says the artist, «was only to create different climates and lighting zones inside the glass case where there is a small boat. In turn, the glass case was placed in the living room of the villa where it originally belonged. At this point I ask myself: what is the place where the filmed action takes place? What is the home territory of the work? The villa? The high seas? A glass case? My imagination?»

What is the role of the artist in the current system of art and society?

Several of us believe that the social role of the artist has dwindled. In the Renaissance, for example, the artist was regarded as an intellectual in relation to matters more or less of public interest: the placement of a square in the town plan, the decoration of a government building, and so on. Obviously, the concept of what was ‘public’ in the Renaissance was very different from that of today. There was a resurgence, certainly as a result of the context of the 20th century and the desire of artists to pull themselves out of a socially active role. I believe that the political art of today does not have a real impact. I think that now the «society of the spectacle,» as prophesied by Guy Debord, has become so real and powerful that it incorporates social action and its possible impact at the very moment it is produced. How do you produce something that has a social impact if you produce it within the institutional framework that it is going to criticize, in an intellectual and irony-fuelled game of mirrors? It is not about intelligence being placed at the service of the people or the political and social sphere, but rather at the service of the ego, of self-indulgence, of agreement with one’s own caste. I am not a political artist, and I acknowledge as much. I can be a political entity of another type. I can be a party member or an activist, but I do not believe in having to make this public in the artistic field, at least not for now. I think today it is really important to understand whether political art has an impact on society or not. I don’t think it does, unless the political criticism reaches a large enough public audience, and by public audience I mean the ‘real’ public, not just the small circle of insiders already aware of the debate.

The Terna Prize, in one of its early editions, published a forecast of the state of the art world from 2010 to 2015. The results showed what is now the current scenario. Among these, there was also the fact that the crisis would have caused the dominant rules to be subverted, as well as more social involvement in art. Is this really what is happening?

It seems to me that during the crisis the art world has closed in on itself even more, it has become highly self-centered and, instead of promoting free research, it has fallen back on its standardized forms, on being easy to use and understand.

What should Italy have (that it does not already have) to encourage creativity and make our country even more competitive at international level? And which country do you believe to be the best from this point of view?

Regarding the effort that our country could make to become more competitive, I think institutional support would be an important help. A country that does not invest in culture is a country that moves backward instead of going forward. I truly believe this, I am not just speaking rhetorically. I think there should be free research, which has never been applied. Of course the commission of a work by a public or private institution is a great thing. However, there needs to be a degree of freedom in research based on a relationship of trust between the artist and the institution.

I do not know whether there is any country that I would mark out as the best. The concept of «best» is always dangerous, since it refers to the abstract idea of perfection that I find counterproductive. I have lived in many countries, especially in Northern Europe. The Netherlands was for many years – now sadly it is no longer the case – a perfect example of institutional support for the artist, as is Scandinavia. For some, this situation of ease does not generate excellence, but rather stasis. Personally I do not think it is healthy to develop as a professional as part of a kind of ‘social experiment’ based on savage Darwinism where adversity creates what is best: I find that truly inhumane. Being constantly put to the test throws up what is best and makes the others succumb: best in what? In artistic sensibility? I do not think that history is filled with many such examples and it does not seem to be a progressive move.

In what direction has your most recent research evolved? Can you tell us about any future projects and plans?

For several years now, my research has been directed toward the tradition of experimental cinema – which is already a tradition because it has been in existence for at least sixty years. Mine is an inquiry into reality that pays a great deal of attention to the object, exploring the relationship between reality and fiction, on the suspension of disbelief and on the veridiction pact with the viewer. Viewers are asked to immerse themselves in a kind of game, to accept the rules of the cinematic game in order to fully enjoy this experience. It is the threshold that interests me most. Agreeing to believe in something that is patently false in order to immerse oneself in it and draw out its meanings. What interests me is this extreme artifice in which one has to «believe». If we want to, that is the key to make an argument on the human or other elements. As an artist, I appropriate something and make it mine, I imitate it, interpret it, I mock it, I make it more humorous, more terrifying, I use it for purposes that are not its own. I have abandoned a tight and classical mounting frame, but I plan to take it up again in the future. I do not plan to dedicate myself to classic fiction films, at least not in the short term. I would however like to take up some form of narrative structure, although still based on objects and non-human elements.

In your work, you prefer cinematic and performative language. How do you regard the issue of conservation?

I think the issue of conservation is very important and very delicate. As regards video, there is a problem of obsolescence which is quite evident. Technologies continue to change, we assume for the better or for the sake of progress and not just for commercial reasons, which, on the other hand, is often precisely what happens. This creates problems in the conservation of these media, in the reproduction of video from earlier periods, or in their transfer. Contrary to what is commonly assumed, some media, such as DVDs and CDs, are fragile and become ruined in no time. For files stored on external memory there is perhaps a little more security, as long as the ports and drivers which connect the external memory to the computer remain the same and there are no issues with compatibility, means or formats. I am concerned about archiving and preservation. I think it’s a good thing to diversify the formats and to create, especially for films and videos, some kind of back-up which is also analogue. One option is to combine ‘local’ archiving with ‘remote’ archiving, through the purchase of shared external memory space which can be accessed at any time via the Internet. With regard to the maintenance of projection equipment, if the archived work requires a particular display, it can be determined on the basis of the description provided in the documentation to get as close to the original display.

Regarding film, the argument is a bit more complex, since it is a format which was born obsolete, especially for 16mm film. The material onto which films need to be printed is now no longer produced. It is sold from stocks and these are running out. Some Super 8 formats are no longer produced and the same thing will also happen with 16 mm. 16 mm is used less and less, just as 35 mm is used less and less. Now people work with the highest quality digital formats and the only markets that still use film are the Asian markets and Bollywood. The entire chain of mainstream cinema has been transferred to digital. I think films on film stock will survive as a technical curiosity, at least I hope, so that projectors and films can be stored and printed, so we will always have them. In terms of time, video is much more prone to obsolescence than film, which has always remained true to itself and is basically a simple machine that guarantees proper working.

Are there any techniques and technologies which are still unexplored by you, that attract your attention and creative curiosity?

I would like to do further research and learn more about the holographic or lenticular printing technique, which in truth I already have some experience of. In the past I produced a hologram taken from a few frames of my films. Lenticular printing relies essentially on multiple prints, superimposed, of subjects which are very similar but have some slight variations, which are developed in their movement intervals. I’m interested in creating objects that maintain within themselves the specific movements of cinema and lenticular printing allows you to do this. Thanks to its progressive sophistication, it will allow us to do more and more. It is already possible to get lenticular multiple prints of more than 5000 frames. It’s as if it was film on a sheet of laminated cardboard; this to me is very appealing.

Terna is a company that deals with providing energy to the country. Its commitment to the Terna Prize focuses on transmitting energy to art and culture and creating a network for supporting and developing talent. Do you think that the Terna Prize formula is still relevant for the promotion of art? Do you have any suggestions for the next edition?

Maybe it could be a production prize: without taking a fee from the artist, it could become a support for new production rather than a reward for what has already been made. This could be an interesting prospect for improvement.

images

(cover -1) Anna Franceschini, You must believe it to see it (Le Tempestaire), 2012. Premio Terna 04 (2 – 3) Anna Franceschini, SPLENDID IS THE LIGHT IN THE CITY OF NIGHT, super8 film transferred to digital, color – mute, 4’16”, 2013. Produced with the support of the Italian Institute of Culture, Paris, video still (4) Anna Franceschini, AND NOW YOU PROMISE YOU’LL NEVER SET AGAIN. Super8 film transferred to digital, b&w, mute, loop, 2013, video still (5) Anna Franceschini, Super8 film transferred on dvd, colour, mute, 49”, looped (shot at 18 and 24 FPS), 2010. Produced with the support of the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten, Amsterdam (NL), video still (6- 7) Anna Franceschini, A SIBERIAN GIRL – 16 mm film, colour – mute, 1’, 2012. Produced with the support of Ex – Elettrofonica, Roma, video still (8) Anna Franceschini, LET’S FUUUUCK! I’LL FUCK ANYTHING THAT MOOOVES! Super8 film transferred to digital, multiple channel video installation, color- sound, 2011 – video still.