The second artist interviewed for the series Survive the Art Cube, is Enrico Pulsoni: a multifaceted personality, Roman by adoption and hard-headed by birth, as he once said during a speech for the presentation of an art book. Listening to Enrico Pulsoni means getting ready to let your thoughts wander in amazing twists and turns, bouncing from one side to the other of the concept under examination. It means opening up an immense reservoir of experience and knowledge, filtered through a limpid, concrete critical attitude without false moralising.

Fabio Giagnacovo: In 1985, Filiberto Menna wrote of his works: “The ambiguity of this painting, its polysemy, which continually eludes any possible definition in iconic and aniconic terms and which seems to play with the observer, making him flash before his eyes, not without a touch of humour, some more immediate and reassuring suggestion, only to divert him, immediately afterwards, to places without points of reference and leave him there in a perturbing suspension”. The same ambiguity seems to me to be an important element in his later works. What does it mean for an artist to be ambiguous? And is the opposite of ambiguity banality for a work of art?

Enrico Pulsoni: Filiberto Menna, with whom I graduated with a thesis on the reconstruction of Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau, had devoted his attention to a series of artists, calling the group Astrazione povera. In the first exhibitions he curated, I was also present, until at a certain point Filiberto told me verbatim: ‘Enrico, you are too evocative’. This, in my opinion, is what he meant by the noun ‘ambiguity’. Ambiguity is to stand on the edge, on the threshold, like the title of one of his exhibitions. Trying never to ‘fit perfectly into a system’. To live life and art with that minimum of detachment from the context that allows you to give vent to your creativity, in all the directions you deem necessary. It is certainly not a position of convenience, because the gallery owner, the collector, i.e. the market, requires a precise location, in other words, your figure.

I still find myself very much in this text from forty years ago. Irony, attraction and detachment are ways of visually diverting the viewer and are an integral part of my work. I look for that strangeness in the image that generates a moment of perplexity in the viewer, something that should resemble the idea of the uncanny. Let us not forget that the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s were characterised by posturing, true self-disclosure, catechisms to fully respond to the dictates of militant and military critics. It is true that no one can disregard his or her context, but being too obsequious of it may bring advantages in the immediate term, but the risk is that, later on, one will find oneself too positioned.

On 30 March 2023, the TeatroBasilica staged the premiere of the plastic-musical work Mortis Humana Via in which his terracotta Via Crucis relates to a series of plaster casts from the limitless VOLTItraVOLTI project, and together, his works become the scenography and conceptual environment of the lyrical performance recounting the last hours of Christ’s life. The religious theme, unlike the more generic spiritual theme, which in waves follows fashions and lifestyles, is a particularly interesting theme in contemporary times. If centuries ago it was the artistic theme par excellence, today it has become almost taboo, just as the taboo themes of yesteryear have become part of our everyday life. What sense, then, does it make in our present – in which novelty dominates over essence, a present immersed in post-liberal individualist exasperation, in which sacrifice is exclusively linked to the materialism of success and its consequences, anxiety and depression above all, are increasingly being pandered to with magic, horoscopes or exotic meditative practices – to work on a theme such as Christianity?

I don’t make a distinction on themes, I prefer to think in terms of themes, which I call cycles, which allow me to analyse an idea that intrigues me. But underlying it all is the obsession to have a karst thread that stitches, mends different subjects and creates a texture that envelops the whole work. I believe, in any case, that an artist’s journey should be assessed in the final analysis and not in the budget.

Mortis Humana Via well exemplifies my progression in time and in the way I move the work forward. The initial moment came from art historian Giuseppe Appella’s request to make drawings of the fourteen Stations of the Via Crucis, in a liturgical version, with a terracotta crucifix for the Holy Week procession. Subsequently, I developed the theme by relating it to graphic research on the theme of identity: the polysemantic VOLTItraVOLTI, which I had been making for some time.

Visually, the result is a huge ring, the circular world, of VOLTItraVOLTI with the fourteen Stations of the Via Crucis in the centre. My reflection is that the life of Jesus Christ with his condemnation, his falls, the pitiful women, the Cyrenean, the spoliation, the crucifixion, resembles what happens to each of us. Who has not been in similar situations? This is the reason why I wanted to place the Way of the Cross as a diameter in the circle-world of this humanity of so many faces that are often overwhelmed by the whirlwind of life.

At this point the work no longer had the liturgical requirements of the Via Crucis and for this reason I named it with Carlo, my brother, Mortis Humana Via, the ‘Human Way of Death’.

I am not talking about the paper version, I felt the need to make it plastic and I remade the fourteen Stations of the Cross in terracotta. For the VOLTItraVOLTI I was helped by Orietta Rossi who modelled them as medals. But Mortis Humana Via was missing something: in my head I visualised it as a strong presence, a silent protagonist but in a musical context.

My brother Carlo wrote the texts for the fourteen stations and three very young composers, Alessio Sorbelli, Desirè Bertolini and Carlo Genovesi, accepted the challenge by writing the score, which includes piano, violin, double bass, soprano and tenor.

The most pertinent definition of Mortis Humana Via is a plastic-musical work.

On 30 March 2023, as you mentioned, Mortis Humana Via is presented in its complete form in the TeatroBasilica and the adjacent spaces of TRAleVOLTE. The operation, as a whole, presents itself as an experiential event: in Giulia Randazzo’s directorial score, the spectator is able to grasp the existential meaning in the passage from the horizontal to the vertical of the work presented.

The metamorphosis just described of Mortis Humana Via from plastic work to performance experience is not new to me because a similar logic was at the basis of Sogni di spettri. These are papier machè characters deprived of context, pirates each caught in their own unstable pose, in that obsession that once made them alive and now fixes them in spectral forms. Gradually I realised that they were begging me to give them a voice. Gianmaria Nerli, recognising them as beings from elsewhere, sensed their hidden message and translated it into words.

Six figures, each of them repositories of a secret, bearers of different experiences and with a specific name and character: The Messenger, who prefers to be a dreamless spectre rather than the dream of a spectre; The Pierced, who experiences the doubt of being condemned to an empathic cycle; The Graft, who, in his inner duality, contrasts the intestinal desire that moves and renews him; La Monocolamonogamba, which incessantly hammers us by beating its tongue; Le Treteste, aware that cities accumulate, stratify, settle one another, letting one see the chain that holds them together; La Trampoliera, which wonders whether one should disappear before inhabiting, or be inhabited.

The realisation that the spectres were no longer just sculptures but figures that had something to tell us, meant that the work also took a technical turn.

How to make these spectres speak was the task of director Giulia Randazzo, who led a triad of actors in performances in Rome, Berne and Basel. Two phases characterise the presentation and performance of Sogni di Spettri (Dreams of Spectres): initially, visitors follow a normal exhibition route, then, at a visual signal and at a pre-established time, they are herded into an adjoining space where actors with papier-mâché masks on the nape of their necks are already present, the connecting element between the talking statues and the acting bodies. The audience, placed in the centre of the triangle formed by the actors, follows the play and, as in a tennis match, continually shifts their gaze from one to the other.

The themes that are congenial to me refer to human nature, the meaning of life and the latent and present fear of being inadequate: that is why trendy themes have no attraction for me.

Your VOLTItraVOLTI, portraits of faces among other faces, found in your urban wandering and translated by your transformative thinking, arise from an exclusively analogue practice and make one think of you as a sort of flaneur who scans the crowd of which you are a part in order to retain some signs of it. In the analogue-digital space, it has become extremely common (never as much as today) to self-represent oneself, to modify one’s features, to transform oneself into an avatar of oneself, to filter any excerpt of photographed reality not through one’s own transformative thought but through the trends imposed by a trivialising and branded community less and less anchored to everyday reality. What do you think is missing from digital? And how important is it for an artist not to be phagocytised by this mechanism?

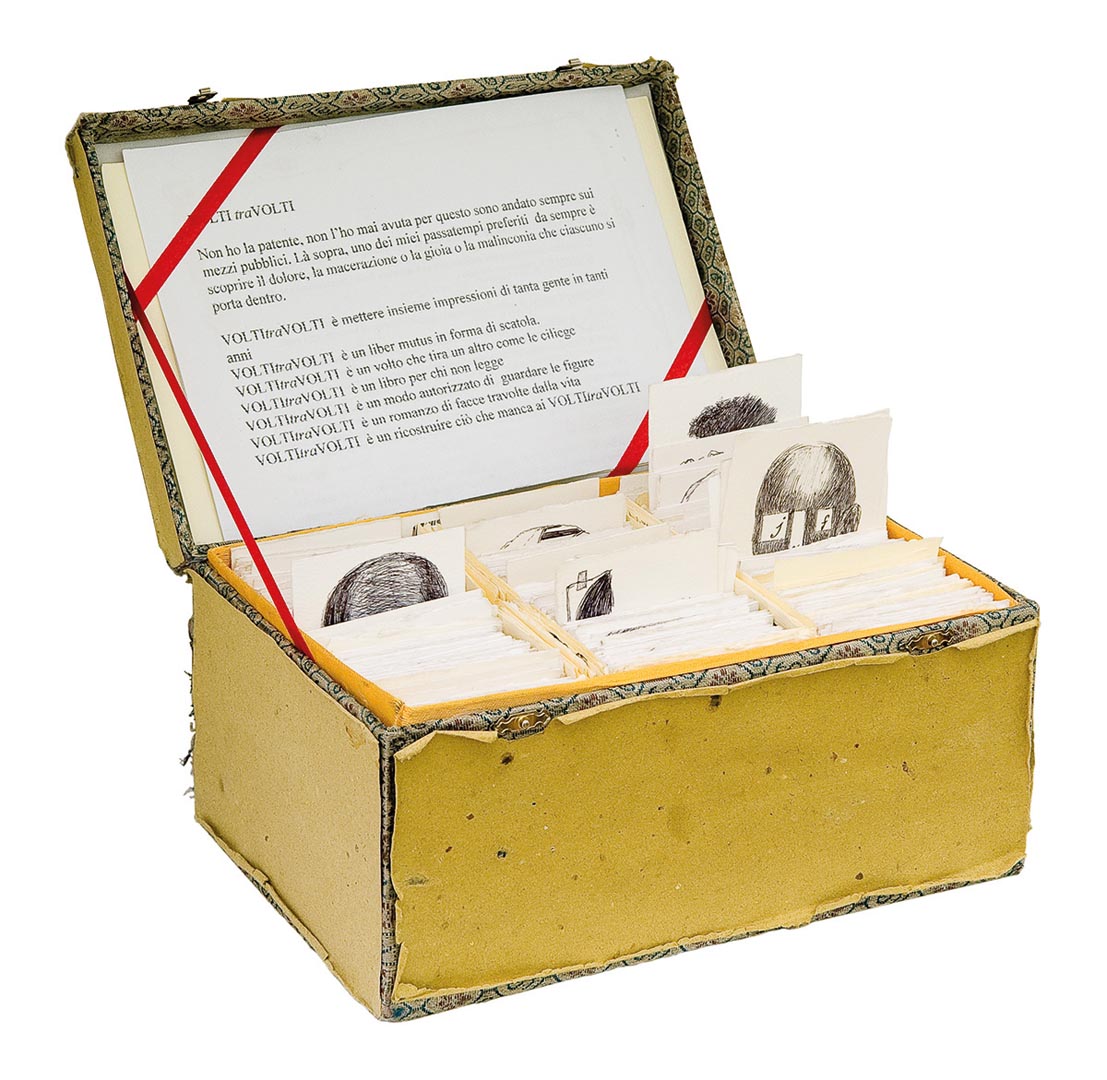

VOLTItraVOLTI are one of several cycles. I would like to point out that originally I tended to privilege hair rather than facial features. So much so that the idea was to lose the features of the figure, to lose the face. The decisive moment was when I had the realisation that hair is composed of hair. I split the word ‘Chiome’, reading it as ‘Chi or Me’ and it became clear to me that my intention was to go deeper into the problem of identity. The growing number of drawings, thousands and thousands, gave me the opportunity to change ‘Who or Me’ into the polysemantic Faces. Here is the accompanying text:

The VOLTItraVOLTI started as drawings, from an original idea by Enrico Pulsoni, who using exclusively black biro made almost a thousand of them on seven by nine cm cards. The original drawings rest side by side in a special box, pressed one on top of the other like sardines or rumours in a market: the pretext is that they can always be had there, as they say, at hand. With these words he presents his box set:

I don’t have a driving licence, I’ve never had one so I’ve always gone on public transport. Up there, one of my all-time favourite pastimes is to discover the pain, the maceration or the joy or the melancholy that everyone carries inside.

VOLTItraVOLTI is putting together impressions of so many people over so many years

VOLTItraVOLTI is a liber mutus in the form of a box.

VOLTItraVOLTI is one face pulling another like cherries

VOLTItraVOLTI is a book for those who do not read

VOLTItraVOLTI is an authorised way of looking at figures

VOLTItraVOLTI is a novel of faces overwhelmed by life

VOLTItraVOLTI is a reconstruction of what is missing in VOLTItraVOLTI.

I am a traveller, mostly for work-related matters, and I am left with facial expressions, particular wrinkles, mouth and eye cuts that I then recompose from memory. A summation of varied and avaricious humanity, which I re-propose in different formats.

As usual, the production of VOLTItraVOLTI became many things: Gianmaria Nerli chose thirty-four and wrote a story about each one, at the same time musician Bernardo Cinquetti composed eight songs about eight specific faces. The result was a book with the songs. We did several performances, similar to jam sessions, during which Nerli would read his lyrics and I would draw live following the rhythms of his voice. On the subject of avatars, many people tell me that the VOLTItraVOLTI are all portraits of me, but it is Flaubert’s story when he says that ‘Madame Bovary is me!

You are an architect by training and an artist by trade, as we read in your biography, not to mention your various activities in theatre and so on. You have different transversal knowledge that makes you what you are. Today, with the exception, to some extent, of artists, the more fluid and fragmented reality is becoming, the more we are looking for hyper-specialised individuals. Don’t you think that this is turning land of flourishing experimentation (not only artistic) into an arid desert of superficiality?

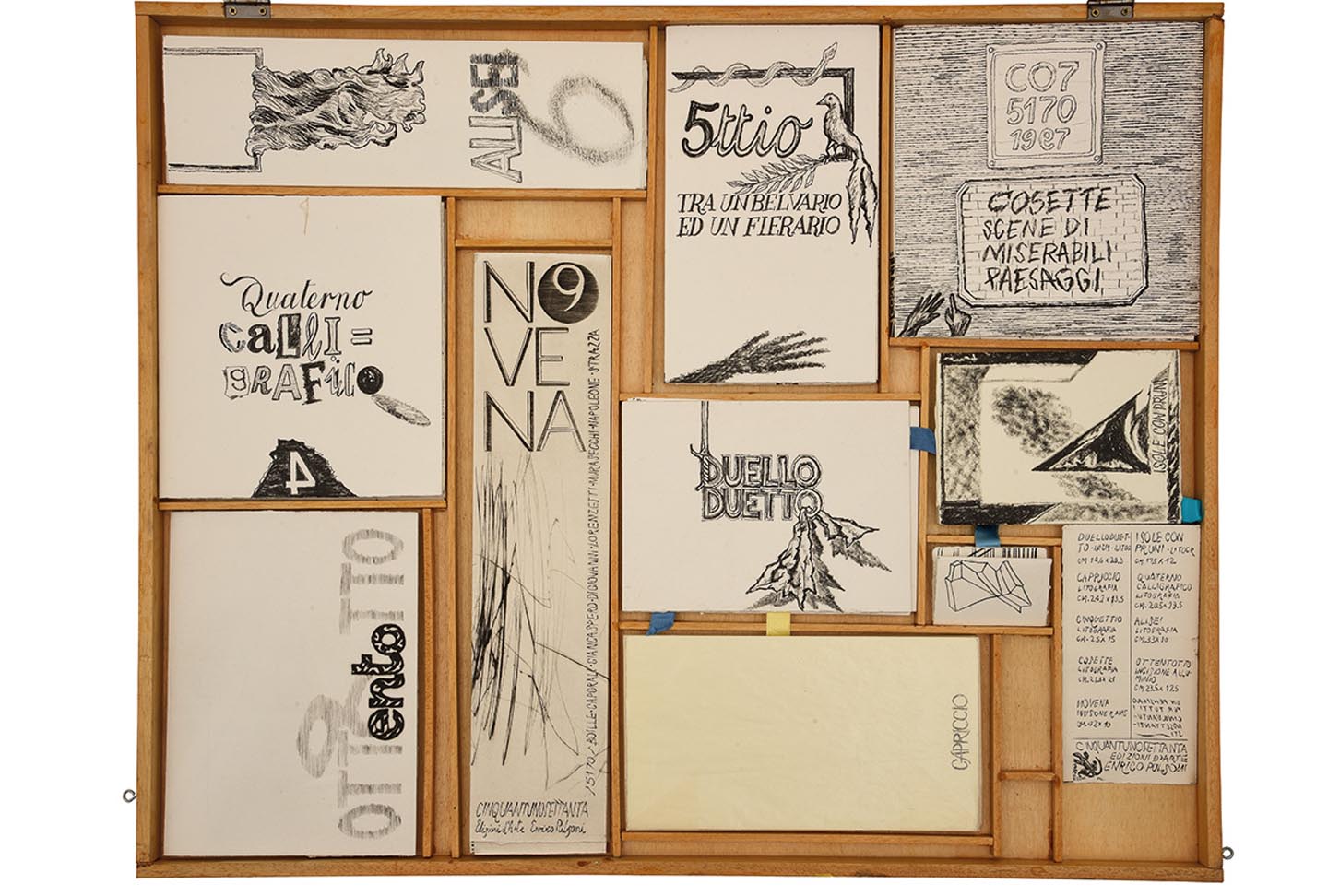

Having participated at a very young age in the theatre group Altro immediately gave me the imprint of collective work, of the way of relating with the most diverse figures. In the group everything was realised by the members themselves. The logic was to construct the space of the scene in which to act. Today, indiscriminate access to technology makes one believe that everyone can do everything, encouraging and reinforcing self-referentiality, one of the aspects of contemporary narcissism. New technologies and in particular digital have never frightened me. I am not a Luddite, but given my age I am still amazed at how many specialisations have disappeared, due to the fact that these technologies delude you into thinking you can make up for so many jobs. Experimentation for me is inseparable from dialogue, which only comes from encounter. In addition to the precedents of Mortis Humana Via and VOLTItraVOLTI, my eagerness for contacts and relationships related to art making has led me to undertake editorial work, producing a series of limited edition artist’s books, which I have named Edizioni d’arte Cinquantunosettanta di Enrico Pulsoni. I ran these editions for about ten years. The cryptic name alluded to the format of the sheet (51 x 70 centimetres), since all the little books would be born from the cutting and folding of a sheet of this size. For all these editions, I used traditional graphic techniques, such as intaglio and lithography. Each book has a different format and layout from the previous ones. This reminded me of the Hully-Gully dance, as each time the number of co-authors I invited to take part in the artistic-cultural kermis grew. My guests, a total of thirty-six people – artists, writers, graphic designers and the like – had to express themselves and confront each other, in the fifty-one by seventy centimetre arena, on a specific topic proposed by me.

The resulting product was a cover sheet with bands, a frontispiece/colophon, and pages folded and folded in various ways with the intention of using the entire sheet.

With this basic idea, I published nine small books:

ISLANDS WITH PRUNES: lithographic solo by Enrico Pulsoni in 29 copies, 17 x 12 cm.

DUETTODUELLO: drawings by Roberto Pace and Enrico Pulsoni, etching and lithograph in 28 copies 14.6 x 20.3 cm.

CAPRICCIO: drawings by Vittoria Chierici, Toni Romanelli and Enrico Pulsoni, lithograph in 45 copies cm. 24,7 x 13,5

QUATERNOCALLIGRAFICO: texts by Valerio Magrelli, Gianfranco Palmery, Jesper Svenbro and drawings by Enrico Pulsoni, lithography in 34 copies cm. 20,5 x 19,5

CINQUETTIO/Tra un Belvario ed un Fierario: drawings and texts by Lucilla Catania, Nancy Watkins, Manuela Giacobbi, Anna Onesti and Enrico Pulsoni, lithograph 30 copies cm. 25 x 15

ALISEI/Ventosi Pensieri: drawings and words by Bruno Conte, Fulvio Ligi, Giuseppe Tabacco, Domenico Vuoto, Henrig Bedrossian and Enrico Pulsoni, lithograph 35 copies cm. 33 x 10

COSETTE/Scene di Miserabili Paesaggi: text by Pietro Tripodo and drawings by Achille Perilli, Tommaso Cascella, Antonio Capaccio, Bruno Magno, Paolo Laudisa and Enrico Pulsoni, lithograph in 34 copies 21.3 x 21 cm

OTTENTOTTO/Esosi Esotismi: texts by Marco Bucchieri, Francesco Dalessandro, Marco Papa and drawings by Paolo Cotani, Ettore Consolazione, Giancarlo Sciannella, Ettore Sordini and Enrico Pulsoni, aluminium engraving in 42 copies, cm. 24 x 17,5

NOVENA: texts by Marco Caporali, Luciano Di Giovanni, Donatella Giancaspero and drawings by Luigi Boille, Carlo Lorenzetti, Gianluca Murasecchi, Giulia Napoleone, Guido Strazza and Enrico Pulsoni, copperplate engraving in 38 copies, cm. 41 x 9,5

In the courses on the Artist’s Book that I taught in the following years, I used the same logic behind these editions. This gave rise to the idea of publishing the poster-handout – with the same format – entitled “Art Book” / Handwritten notes for books to be made by hand.

I reiterate that experimentation is born and grows out of encounter and dialogue, which allows me to state that my work is nothing but a reflection on ‘our being in the world’, grasping its problems and giving an account of them in a non-ideological manner. To conclude, I would like to point out that for some time now I have been having my 8 Mementi molli, large papier maché sculptures, scanned in 3D so as to make models of a few centimetres that I call ornaments: for me, every analogue or digital tool in a perspective of artistic realisation is not only useful but indispensable!

You were a professor of set design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Macerata for several decades. What idea have you gained of these institutions over the years? And are the employment problems of their graduates (pardon me, graduates… the same term you use for secondary schools) attributable more to them or to their members? Coming out of private academies it is undeniable that it is much easier to find work, in the end it is just a question of money then?

Let’s start from the end: private Academies deal with a smaller number of students, compared to State Academies, which gives them the opportunity to forge much more direct relationships with the working world. This service turns out, I am told and I have no difficulty in believing it, to be the driving force behind the success of private Academies, and the reason why they can charge high fees.

As far as the State Academy is concerned, I think it is following the same path as the University with regard to the multiplication of courses. An Anglo-Saxon approach that aims at hyper-specialisation of disciplines. I remain faithful to the training I received, the principle of which was to start from complexity and gradually narrow the field of study. Another limitation of the State Academy was the lack, until very recently, of the ‘PhD’, a fundamental opportunity to chart a clear path for the most deserving students in an academic career. I consider my experience as a lecturer to be positive, apart from a few problems with transfers, having been able to establish agreements and collaborations with Institutions, Bodies and Foundations, both within and outside the territory. Furthermore, the Erasmus Project was an opportunity for international contacts that allowed interesting exchanges of teaching methodology. All this would not have been possible if I had not had collaborative colleagues with whom to share experiences in different fields. It is with great satisfaction that I can say that many of my students have been introduced to the environment, and are building their future in the field of theatre and film set design, and also in different aspects of the art world. Of this, I am sincerely proud.

Enrico Pulsoni, architect by training and artist by trade, has held the Chair of Scenography at the Academy of Fine Arts in Macerata and coordinated the cultural activities of the Rome branch of the Filiberto and Bianca Menna Foundation. He trained with the Altro theatre group, exhibited in Italian and foreign galleries, and collaborated with art publishers and literary magazines. In recent years, his production has focused on a number of cycles, among which the “Le sette creazioni” and “Sogni di spettri”, in collaboration with Gianmaria Nerli and Stefano Sasso. The most recent exhibition ‘“8 Mementi Molli e altre narrazioni”, curated by Antonello Tolve, took place in the Rome premises of the Fondazione Filiberto e Bianca Menna (from Archivio Enrico Pulsoni).

“Survive the Art Cube” is a series of interviews with artists from different generations. The title borrows from Brian O’Doherty’s most famous book to echo its critical slant. It aims to better understand how these artists perceive the analogue-digital space in which we are immersed and our contemporaneity, what sense and importance artistic space has today and what sense it makes in our present to make an artistic journey. Dark times call for reflection on reality and only artists, perhaps, can open our minds.

images (cover – 1) Enrico Pulsoni, Illustrazione di Nikla Cetra (2) Enrico Pulsoni, VoltiTraVolti, 2009-2010, acrilico su carta, 70x50cm (3) Enrico Pulsoni, «VoltiTraVolti», 2006-2022, copia unica, 11x25x17cm (4) Enrico Pulsoni, «Messaggera (dalla serie Sogni di Spettri)», 2011-2015, tecnica mista su cartapesta, 125x60x50cm (5) Enrico, «Mortis Humana via al TeatroBasilica» (6) Enrico Pulsoni, Edizioni d’arte Cinquantunosettanta, 1991-2002 (7) Enrico Pulsoni, Illustrazione di Nikla Cetra