It is probable that everything took off with the invention of photography in the 19th century, with the arrival of a new way of structuring the visual experience. From the day of its invention in 1839, the world became an infinite collection of images that is comparable to the idea of an enormous archive. Lev Manovich[1] focuses on one of the key forms of today’s technology: the database. If perspective was the «symbolic form»[2] that characterised art from the Renaissance to Impressionism, the archive can be considered as a new way to conceive space, a symbolic form of the contemporary era, whose origins can be traced back to the mid-20th century – and way ahead of its time in comparison with the digital era.

Pablo Picasso inaugurated this new symbolic form by using collage, taking from everyday life newspaper clippings, musical scores, wallpaper and anything else he could glue to a canvas. With the inclusion of waxed material to imitate a stuffing, Picasso perfected the new invention of collage by presenting objects that were no longer evoked through the pretence of painting since they simply existed on the canvas. Another great artistic intuition produced during the first half of that century bears witness to the fact that 20th century art conceptually adopted the logic of the archive: ready-made. By choosing commonly used industrial products, Marcel Duchamp limited himself to indicating a series of already-created objects as art: a bicycle wheel, a bottle-rack, a porcelain urinal. The French artist might be viewed as a sort of ante litteram internaut on a constant quest for objects that would interest him much in the way we now surf through the multi-media information we find on Google, YouTube and Facebook. A similar argument could be made for Giorgio De Chirico’s Metaphysical painting; the artist was actively involved in a temporal journey that led him to remembering all information from the past and re-introducing it in original combinations.

Andy Warhol was the man who continued this exploration within the vast quantity of pre-packaged visual information during the second half of the 20th century. While Duchamp’s archive was made up of objects, Warhol’s was made up of images. We could see a society in the 1960s as one built around a large archive that the artist used according to his fancy: expanding, multiplying and transforming it into art – dictators, Hollywood divas, dangerous criminals and canned food. This operation of photographically drawing upon mass-media is probably the most followed route of future generations like Gerhard Richter and Christian Boltanski or (in Italy) Franco Vaccari and Adriano Altamira until the 1980s with the explosion of a phenomenon defined by Hal Foster as «An Archival Impulse»[3] and by Okwui Enwezor as «Archive Fever».[4]

More recent works by American artist and winner of the Golden Lion at the 2011 Venice Biennale Christian Marcaly come to mind. The Clock is a video made up of portions of films from all eras in which actors interact with a clock, watching it, pointing to it and speaking of it. The novelty introduced by Marclay consists of transforming the video itself into a clock, making it last 24 hours and synchronizing it with the real time of the spectator. Through this and previous works, film becomes revitalized, and distances itself from the logic of the story and the link to literature which often limits its potential.

The digital revolution has contributed to further accelerating the new symbolic form based upon drawing upon things and the archive. In fact, a change that stretches beyond the easy access to date hides behind the digitalization of an image in that there is a possibility of no longer interpreting photography as simply the «representation» of the world but as the «presentation» of a series of relations that go beyond what is visible. In the words of Pierre Sorlin: «computers work on the entity that the eye will never perceive and thanks to that, logical reasoning will prevail upon direct observation».[5] The passage from analogical to digital brings new lifeblood to the image because it makes it suddenly shareable with others while maintaining its identity intact. If this were not the case, it would be very difficult to understand the success of the many social networks, databases, digital or digitalized images, attracting millions of people. These users do not interpret photography as a perspective mirror of the world, much less as an object, but rather as customizable information to share with a capillary network of contacts that change meaning through various passages, stimulating the game of relations.

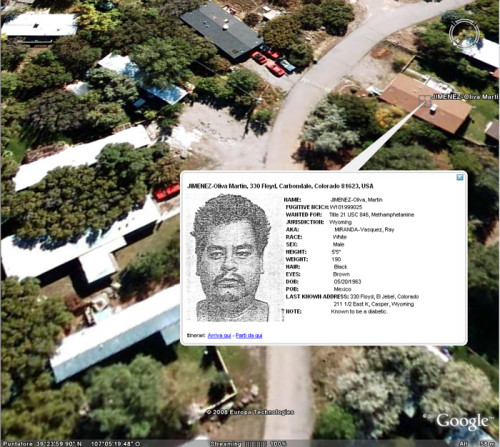

Nowadays the content offered on line can be created by the users themselves. An example of this is the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia whose entries are the result of the interaction of a participatory community. Among the artists moving in this direction, we have the group known as Alterazioni Video who explore the conventional border between legal and illegal use of technology. In the video Last Known Address, the artists are on a virtual journey through America from inside the Google Earth application, following the last known addresses of those wanted by the DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration); a community of dangerous criminals whose names are posted on the American anti-drug trade agency’s website. The material found on the web is re-interpreted by Alterazioni Video and, as new authors; they offer other possible meanings to the texts and images. Using a similar operating mode, artist Naomi Vona focuses her work on the analysis of media phenomena, leading her to observe the world through YouTube. She found the trailer to the much discussed Brazilian porno-fetish film Hungry Bitches, known to the internet population as 2 Girls 1 Cup. The vision of this film resulted in the idea of making a video connected to the common emotions experienced by those who voluntarily filmed themselves in front of a webcam while seeing the trailer, archiving them through an incessant and rapid editing of the faces that quickly changed expressions. This video by Vona is called Gli infedeli mediatici (The media infidels) and shows the faces of a virtual community of users – embarrassed at first, then reluctant and finally disgusted – who could not resist watching the film. Their initial incredulousness, which had driven them to watch even though the content of the film was obvious, was negated by the visual confirmation of what was running in front of their eyes was actually true. We can deduce from this brief x-ray of contemporary lifestyles that the idea of the archive can be considered as a different logic, a new «symbolic form» capable of transversally representing the past one hundred years of artistic expression.

[1] L. Manovich, The Language of New Media [2001], Olivares, Milan 2002.

[2] E. Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form [1927], Feltrinelli, Milan 1993.

[3] H. Foster, An Archival Impulse, «October» n. 110, New York 2004.

[4] O. Enwezor, Archive Fever, ICP-Steidl, New York-Göttingen 2008.

[5] P. Sorlin, Les fils de Nadar [1997], Einaudi, Turin 2001, page 231.

Images

(cover e 1) Naomi Vona, Gli infedeli mediatici, 2009 (2) Alterazioni Video, Last known address, 2008 (3) Christian Marclay, The Clock, 2010.