Today we can hardly distinguish between the digital and non-digital realms of contemporary reality that reflects in arts and humanities. Most 1960s and 1970s digital artworks are actually hybrid in nature: they used both analogue and digital technologies. This trend developed into a digital-born art dominating around the turn of millennium, and came back again swinging the full historic circle — but now created within the post-digital conditions.

The historical distinction between the digital and the non-digital has become increasingly blurred, and we suggest to take a closer look at particular examples of early digital art from 1960s and 1970s and its international networks at the time, both [New] Tendencies and E.A.T. (Experiments in Arts and Technology).

An inaugurating international exhibition under the title new tendencies took place in1961 At the Zagreb’s Gallery of Contemporary Art (today Museum of Contemporary Art) , This event developed into an international movement and network of artists, gallery owners, art critics, art historians, and theoreticians, transgressing the Cold war barriers and exhibiting both artist from both sides, the proverbial East and West They presented instruction-based, algorithmic, and generative art. Following the rationalization of art production and the conception of art as research that was theoretically framed by Matko Meštrović, Giulio Carlo Argan, Frank Popper, and Umberto Eco, among others, New Tendencies was open to new fusions of art and science. Light and movement were the new materials, shaping art styles as luminokinetic art. Participation with artworks was understood to be an examination of democratic political praxis, and visual research was seen as a way of learning it. When, by the mid-1960s, such tendencies made it to the mainstream of contemporary art by winning prizes at the Venice Biennale and reaching big institutions such as MOMA in New York (when the term Op Art was inaugurated and things got commercialized), New tendencies organizers started to “reach new leaps into the unknown (Putar, 1969). They have organized series of symposia and exhibitions under the programmatic title Computers and Visual Research.

Having cultivated a positive attitude towards machines from the beginning, New Tendencies adopted computer technology via Abraham Moles’ information aesthetic. Its organizers saw this as a logical progression of New Tendencies. The new interest in cybernetics and information aesthetics resulted in a series of international exhibitions and symposia on the subject computers and visual research, which now took place under the umbrella of the rebranded events tendencies 4 (t4, 1968-1969) and tendencies 5 (t5, 1973), after the prefix “new” had been dropped from the name in 1968. Brazilian artist and active NT participant Waldemar Cordeiro’s statement that computer art had replaced constructivist art can be traced through the histories of the both “analogue” and “digital” [New] Tendencies network themselves. The years 1968 to 1973 were heydays of computer-generated arts not just in Zagreb but around the world; computer arts began to be distinguish from other forms of media and electronic arts. As it has always been the case in the field of media arts, a technologically deterministic and techno-utopian discourse and a critically minded and techno-dystopian one co-existed. The ambitious tendencies 4 program begun in Zagreb in the summer of 1968, parallel to another milestone event: Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition in London. Unlike any other exhibition, the formal criteria applied in the selection of “digital” works for the exhibition in Zagreb were rigorous; flow-charts and computer programs of digital works were requested, and the artworks by pioneer Herbert Franke, created by means of analogue computing, were not included but presented in a parallel 1969 exhibition titled nt4 – recent examples of visual research, which showed analogue artworks of previous New Tendencies styles. Between 1968 and 1973 more than 100 digital arts practitioners within [New] Tendencies presented their works. The last exhibition, tendencies 5, consisted of three parts: constructive visual research, computer visual research and conceptual art. This combination made [New] Tendencies the unique example in art history that connected and presented those three forms and frameworks of art – Concrete, Computer and Conceptual — under the same roof.

In connection with the tendencies 4 and tendencies 5 programs, nine issues of the bilingual magazine bit international were published from 1968 to 1972. The editors’ objective was “to present information theory, exact aesthetics, design, mass media, visual communication, and related subjects, and to be an instrument of international cooperation in a field that is becoming daily less divisible into strict compartments” (Bašičević and Picelj 1968).

Computer-generated art’s attraction gradually faded from the art world at large during the 1970s. Computer graphics of the 1970s explored possibilities for figurative visuals and — by delivering animations and special effects for the mainstream film industry — entered the commercial world as well as the military sector, advancing virtual reality techniques that simulated “real life.” In the larger context of an increasing dominance of conceptual and non-objective art building on post-Duchampian ideas of art and representation this development led to the almost-total exclusion of computer-generated art from the contemporary art scene around the mid-1970s. This process was further fueled by the rising anti-technological sentiment among the majority of the new generation of artists, created by the negative impact of the military-academic-corporate complex’s use of science and technology in the Vietnam War and elsewhere. It is pity that computer installation that endlessly print anti-Vietnam war slogan Nixon Murderer by Remko Scha, conceived and written in ALGOL program in 1969 had not been realized until this very exhibition. It may well have influenced and inspired politically engaged digital art at a time it was practiced only by very few artists. In the mid-1970s major protagonists in the field of digital art, such as Frieder Nake, Gustav Metzger, and Jack Burnham, shifted discourses on art, science and technology, openly criticizing developments of the digital arts field. In Zagreb the [New] Tendencies movement drew back: tendencies 6 started after 5-years of preparations by the working group who couldn’t come a consensus on how to contextualize and support “computers and visual research”. Finally the group agreed on organizing only an international conference tendencies 6 – Art and Society in 1978 where, again few computer artists met with conceptual art practitioners who were now the majority.

During 1970s only few digital art practitioners succeeded to merge the new sociopolitical critique with digital arts. One of rare examples is the Mobilodrom, a 1979 project by Michael Fahres. In this work, an electric car drives through the city and collects environmental information like temperature, air pressure, volume and pitch of environmental sounds, movement and others. These data were translated in real time into sounds by a computer and final sound output was performed by an analog music synthesizer and speaker system. We may well see such analogue-digital hybrid urban mobile machinery operating real-time interactive and socially engaged content, using the same or similar kind of inputs and outputs in both media-art and contemporary art festivals and exhibitions around the world at this very contemporary post-digital moment of the 2010s. Fortunately, in art there are always unknown unknowns.

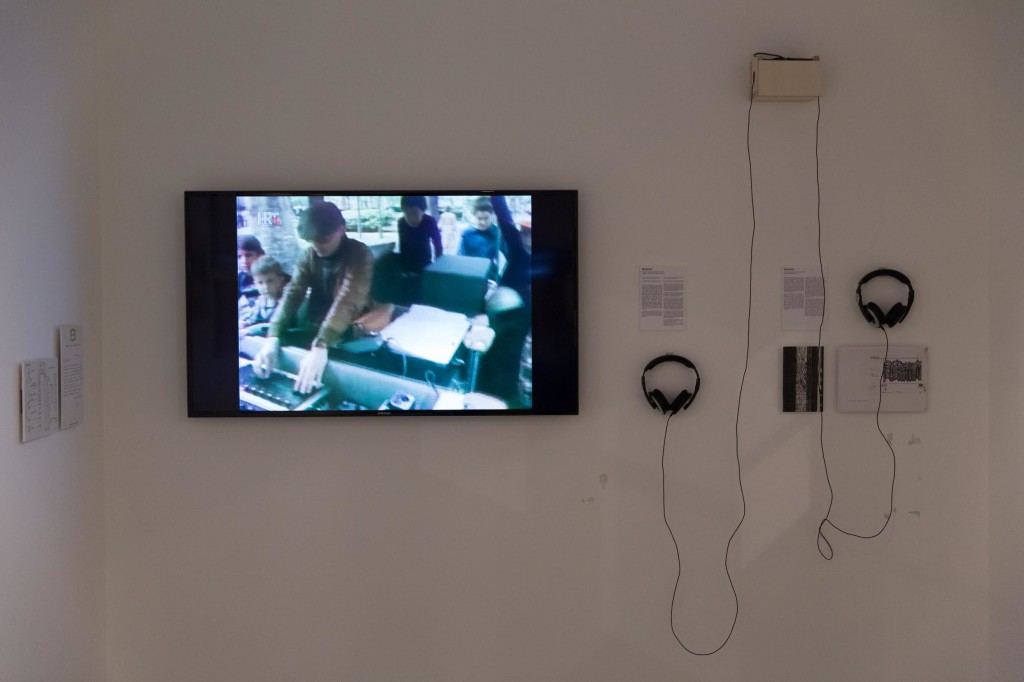

This essay by Darko Fritz introduced the show: Histories of the Post Digital: 1960 and 1970s Media Art Snapshots organized in Istabul in 2014-2015. It is here translated in Italian and reproduced with kind permission of the author. Complete reference at: Histories of the Post Digital 1960 and 1970s Media Art Snapshots, catalogue of the show, curated by Ekmel Ertan and Darko Fritz at Akbank Sanat (Istanbul), 17.12. 2014 – 02.21.2015, pp. 10-11, also available here for free download.

The exhibition was reviewed by Antonello Tolve on Arshake on January 25, 2015

Images (all): «Histories of the Post-Digital:1960s and 1970s Media Art Snapshots», AKBANK SANAT, exhibition view