Eva Kekou interviews Caherine Nichols, an arts and literary scholar, curator and writer, specialised in trans-disciplinary experimental exhibition practices, who is currently creative mediator for Manifesta 14. She talks about the path that led to the current edition of this nomadic biennial, its political impact on Phristina, its host city, and much more.

Eva Kekou: Can you please describe how you envisioned the Manifesta project upon curatorial commission?

Catherine Nichols: What’s captivating about developing the artistic programme for Manifesta, which, as you know, is a nomadic biennial, is that it comes with a very different and shifting set of parameters and objectives than sedentary biennials like Venice, São Paulo, Gwangju, Singapore or Sydney. This model of biennial, assiduously evolving under the leadership of director Hedwig Fijen, is always about exploring and responding to the needs and desires of a specific city and its citizens – in this case Prishtina – as opposed to bringing in a new theme and curatorial approach every two years to the same city.

So, when I joined the Manifesta team in the summer of 2021, my task was to respond on the one hand to the objectives articulated by the city in its bid to host the biennial and on the other hand to the findings of the pre-biennial research process. This process, which included urbanological investigations led by Carlo Ratti Associati and the MIT Senseable Lab alongside many citizens’ consultations and assemblies, played a crucial role in mapping the infrastructure of the city and identifying sites of feasible intervention.

I began by visiting these sites, meeting with all kinds of different people, whether artists, architects, urbanologists, sociologists, students or schoolchildren writers, historians, workers, thinkers or activists, and thinking about what kinds of artistic, architectural, social, scientific practices could play a transformative role in the city.

The idea for the overarching theme – “it matters what worlds world worlds: how to tell stories otherwise” – came to me when I realised the extent to which people in Kosovo were already using collective storytelling to grapple with the past and to enact social transformation. Choosing this topic was a way of taking up and building upon what is already there.

The title cites American theorist Donna Haraway, whose thinking around “storytelling for earthly survival” played an integral part in the conceptualisation process. So did Hannah Arendt’s exploration of storytelling as the means by which we enter the public realm and, as such. the condition of politics.

Which challenges did you have to overcome and how this has been over the years/curatorial process developed?

I think the greatest challenge I faced was the rather limited amount of time I had in which to immerse myself in the history and cultural landscape – not only of a city and a country but also of an entire region. Insofar as Manifesta 14 Prishtina had set itself the objective of strengthening ties and cooperation across the region and always endeavours to be as situated and embedded as it can, I wanted to get to know as many people and their practices as possible.

Because cultural activities are so chronically underfunded and artists suffer from an endemic lack of visibility, it wasn’t as easy as it might be elsewhere to locate emerging artists and to view their work. There are very few exhibitions, and not many artists have studios, publications or comprehensive websites.

The good thing is that people are very networked, at least within the individual cities if not between them, and in general everyone’s exceptionally warm, welcoming and quite supportive of one another, so it didn’t take that long to find my way around. The participation of over 150 artists and collectives in an open call for projects from Kosovo and the Kosovar diaspora also helped to strengthen my overview of the scene.

The complex history and politics of Kosovo and the former Yugoslavia also take a lot of time to grasp. It’s one thing to acquire a working knowledge of the issues the various post-conflict societies across the region are grappling with and another to actually work with that knowledge in a meaningful way. Here again, people have been very helpful in suggesting literature to read, experts to consult, what to look out for and be wary of. The most helpful resources have been the Kosovo Oral History Initiative and the online independent media platform Kosovo 2.0.

In which ways Kosovo has been an appropriate curatorial “target” and why do you think that Balkans can be of great interest to us?

As I mentioned before, Prishtina sought to host Manifesta for many reasons. The city believed that the biennial could support its citizens in their ambitions to reclaim public space, to expand and strengthen forms of participatory democracy, to extend the cultural infrastructure beyond the boundaries of the inner city, to establish and maintain spaces for well-being, to improve diversity and inclusivity in the cultural fields, to reduce pollution and to make the city greener.

At the same time, people hope that biennial will help to widen the narrative framework in which Kosovo is seen internationally. While people feel that it makes sense to acknowledge the role that war and transitional justice play in shaping that framework, many yearn to go beyond the restrictions that go hand in hand with narratives of violence; and many are eager to increase visibility for the artists, writers, filmmakers, thinkers, makers, for the issues with which they’re engaging and to simply show people the quality of the work coming out of the country. Working with the local and international team members to address such objectives is probably as stimulating and meaningful as curatorial work can be.

Now that we’re several weeks into the biennial it’s becoming evident that visitors have in fact been yearning for the same thing: a more complex understanding of the stories and strategies at work in Kosovo and the region often referred to as the Balkans. From everything I’ve heard, visitors are very interested in examining the dynamics of the post-socialist and post-conflict societies, intertwined as they are with the mechanisms of turbocapitalism. These they encounter as much in the twenty-five venues comprising the parcours as they do in the projects they see, in the events held at the Centre for Narrative Practice, an institution founded as part of Manifesta 14 which will continue after the biennial, or the programme of the Centre’s recently launched online radio platform Radio Otherwise. More than anything else, I think people right across the world are keen to look into strategies of healing, repair, resistance and resilience. As you can see at the biennial, there are many works and projects coming out of southeast Europe that deal with these questions in insightful ways, from teaching science fiction writing to designing architectures of healing.

In which ways have Pristina’s public space and unused buildings been activated? and how different is public space being used and perceived?

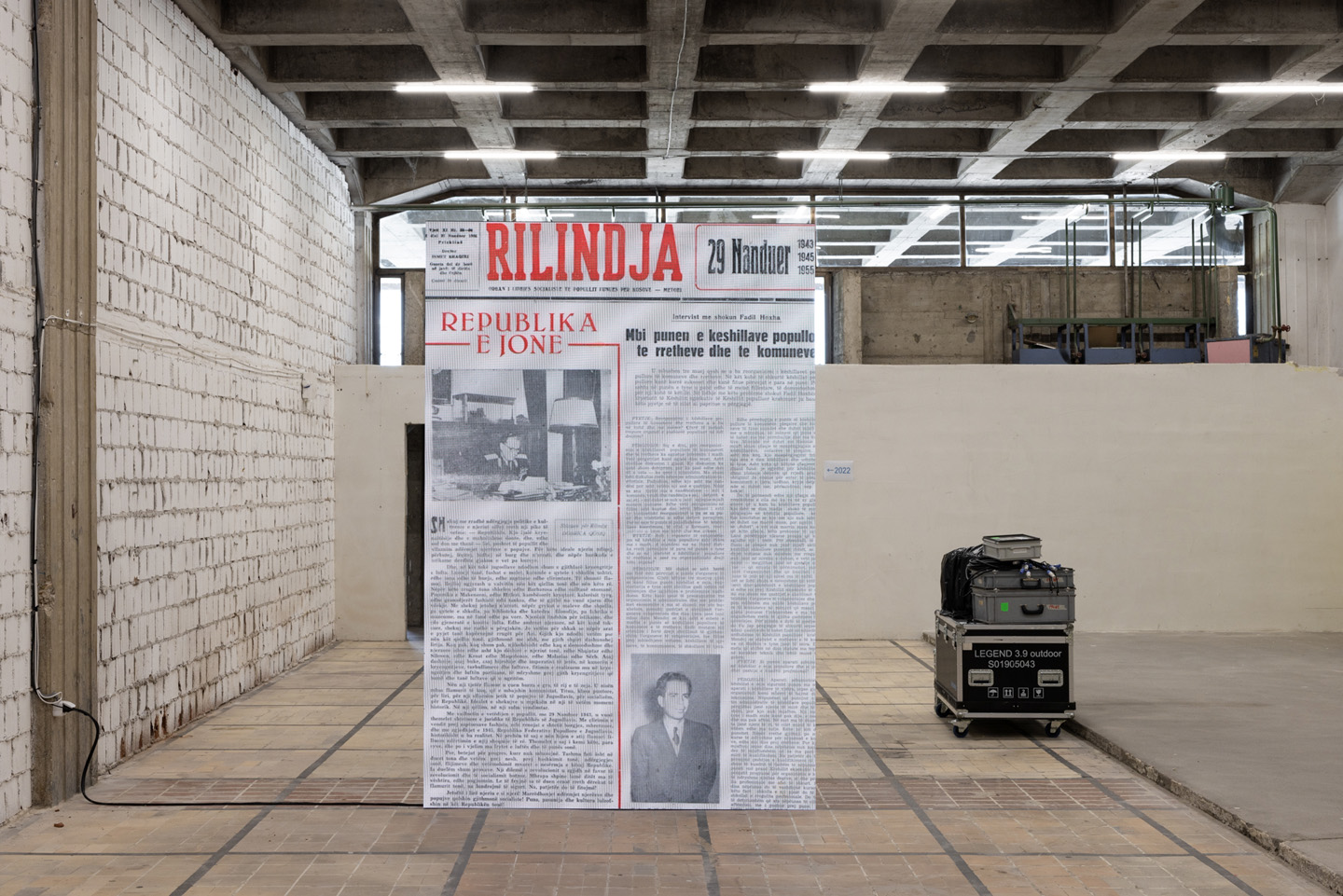

Three major urban interventions have been the transformation of the derelict Hivzi Sulejmani Library into the lively Centre for Narrative Practice, the revitalisation of the defunct Brick Factory to test its viability as a cultural hub and the establishment of a Green Corridor, a pedestrian path along a disused railway line connecting the Brick Factory to the Palace of Youth and Sports in the heart of the city. Many of the twenty-two other venues also present variously nuanced ways of engaging with dysfunctional buildings, such as Chiharu Shiota’s installation at the Great Hammam, a bathhouse which hasn’t been used since the 1960s, Christian Nyampeta’s film at Kino Rinia, a beautiful historic cinema only just saved from becoming a bathhouse, or Cevdet Erek’s installation at Rilindja Press Palace, a now empty publishing house where the first Albanian-language newspaper was printed. The most significant effect of these many interventions has been that people from Kosovo have – often enough for the first time – been visiting and reconnecting with sites of historic importance that had drifted out of their consciousness. The first step in reclaiming public space is, of course, noticing it and entering it. And once you’ve entered, the stories you uncover or encounter as you move around the space, the things that make you think, alter – or establish – the relationship you have with the place.

I would like you to comment on the narrative that has unfolded through the curation in different buildings and spaces across the city of Pristina?

If I were to subsume under one word, under one title, the multiple narratives that unfold across Manifesta 14 Prishtina, the word would be “otherwise”: the biennial is about using narrative practices, individual or collective, to bring forth new, more humane, more sustainable stories, to conjure up a more tenable otherwise.

In the selected works video art has a prominent role? Why do you think that video art and films play an important role in the cultural art scene in the Balkans and in which ways video helps us to have an in-depth understanding and connect art with politics?

Video art is quite prominent in the art scene in the Balkans as it is across the world. It’s a medium which, whether documentary or fiction or both, accommodates a plurality of voices and layers of stories. One reason many people in the Balkans work with the medium is because it doesn’t necessitate having a studio. Since studios are expensive and hard to come by, many artists drift into video because you can work on it at the kitchen table or in bed.

How political has Manifesta been this year? and in which it has been an achieved aim to send out political messages?

I think that Manifesta is inherently political insofar as it heightens international awareness of the political situation of the cities that host it, and insofar as it seeks to work with the citizens of a given city to transform social infrastructure, to create new imaginaries, enhance political imagination and most of all to encourage participation in political processes and civil society. Each city comes with its own political landscape. Palermo is different from Marseille and Marseille is different from Prishtina, the capital city of Kosovo, a country struggling to have its sovereignty recognised and visa restrictions lifted. Since it’s the first edition of Manifesta I’ve worked on, I can’t really answer the question of whether Manifesta this year has been more political than other years.

Which has been the response by audience, visitors, guests and professionals so far?

The response has been positive. We’re very happy with the visitor numbers. People seem to be much enjoying exploring the city and its intriguing architectural sights and monuments. Even locals have been telling me that they’ve enjoyed using a map for the first time in their own city, discovering and rediscovering places they’ve been walking past year after year. The appeal of encountering a broad spectrum of artistic practices from Kosovo and the region interwoven with has also featured strongly in the reviews. The fact that entry is free has meant that visitors of a very broad demographic have been coming. On day one we encountered a ten-year-old boy who had come to the Grand Hotel on his own to visit the city’s first international biennial.

In which ways working in a southeastern Balkan country with all complexity culturally involved in its own context has been a challenge for you as a curator, a female Australian curator in particular?

As I mentioned, the complex history and politics of this part of the world are challenging to any outsider. Indeed, they are challenging enough to any insider. I don’t know if I would ever feel as though I were on stable ground, forever navigating conflicting histories amid residual trauma. Yet I’m part of a very large, well-informed team of people and in contact with countless others from all different parts of society. Because I’ve often had my dog with me while I’ve been travelling around the region, all kinds of different people have stopped me to talk. Somehow having a dog makes you more approachable, brings you into contact with people you wouldn’t otherwise meet. So, I’ve been listening and reading carefully and asking a lot of questions, doing my best to ensure that I bring the necessary sensitivity into my contribution to the overall programme.

Being Australian has been helpful in some ways. On the one hand, I know many people who have come in various waves of migration to live in Sydney where I grew up, some in the 1960s, others in the 1990s. Living in Berlin, I’ve also got to know many people from Southeast Europe. So, working in the region hasn’t been a culture shock as such. On the other hand, it’s been good to be an outsider, to enter the scene without any prejudices or allegiances.

I can see that Kosovo is not an easy place for women to work. Alicja Rogalska’s work Sister Flats, which is situated in a private apartment, makes plain the challenges involved. That said, I haven’t personally experienced discrimination in Kosovo. People have been extraordinarily warm and kind to me.

MANIFESTA 14, curated by Catherine Nichols, Phristina, 22.07 – 30.10.2022

images: (cover 1) Under the Sun – Explain What Happened, 2022, © Flaka Haliti. Photo © Manifesta 14 Prishtina, Ivan Erofeev (2) Green Corridor, 2022, © CRA-Carlo Ratti Associati. Photo © Manifesta 14 Prishtin, Ivan Erofeev (3) Sometimes It Was Beautiful, 2018, © Christian Nyampeta. Photo © Manifesta 14 Prishtina, Ivan Erofeev (4) Amator Archives, 2022, © Werker Collective. Photo © Manifesta 14 Prishtina, Ivan Erofeev (5) Working on Common Ground, 2022, © raumlaborberlin Photo © Manifesta 14 Prishtina Ivan Erofeev (6) Brutal Times, 2022 , © Cevdet Erek Photo © Manifesta 14 Prishtina Ivan Erofeev (7) PËRTEJ – Archiving Transition, 2022, © Foundation 17 Photo. © Manifesta 14 Prishtina, Majlinda Hoxha (8) LYNX , 2022, © Astrit Ismaili. Photo © Manifesta 14 Prishtina, Esad Duraku (9) LOVE is LOVE is LOVE, 2022, © Sekhmet Institute with Ermira Murati. Photo © Besfort Syla