Like a painter en plain air, Quayola explores the relationship between nature and technology through the algorithmic lens, and its vitality. To achieve this Quayola uses the most classical traditions involving the reconstruction of archetypes, the deconstruction and stratification of matter, and the research of form in the translation of movement. Quayola reveals his creative process and introduces his most recent work, now on show at the Charlot Gallery in Paris.

The relationship between nature, art and technology is at the basis of all your research. How do you envision nature in the close future, now that the merging of organic and inorganic is becoming a matter of fact?

In my work I explore collisions between opposing forces, like old/new and real/artificial.

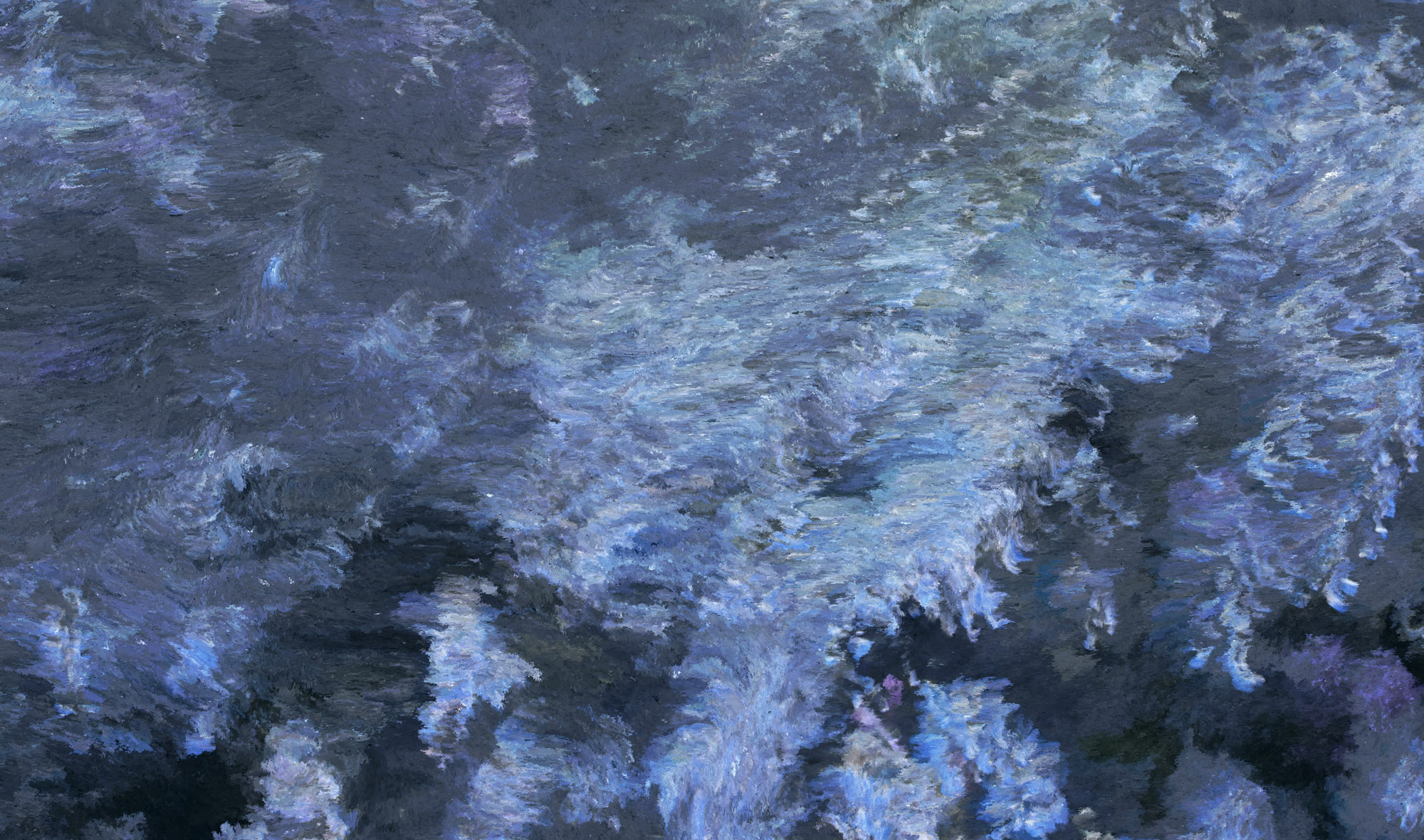

Looking at the historic tradition of landscape painting, I am intrigued by how Nature as a subject becomes a point of departure to generate new aesthetics and new ways of seeing… I am therefore interested in Nature in a somehow primordial state, untouched, which I observe through highly technological apparatuses.

The result in my works are hybrid visions, however not focusing on new ideas of ‘hybrid-nature’, but on entirely new ways of perceiving something primordial and absolute… ultimately my research investigates new modes of visual synthesis.

Several times, you stressed the central role that the process plays in your work. What role plays sound and sound-processing?

In Jardins d’Été the sound helps to shape matter. Sounds were captured from nature and then elaborated with code. What input or criteria did you give to the machine in order to reach the final effect?

In all my video works sound plays a crucial role. It is very important for me to have something so ephemeral like a digital video/animation become tangible, almost physical. Highly synchronised sound help bringing my digital works into this physical realm, so the spectator really engages with them as sculptural objects.

In Jardins d’Été the sound is processed in a similar way to the video – original recordings of various organic textures are processed with various algorithms following the dynamics of the animated paintings simulations.

One criteria was related to how visible/readable is the original floral composition, so basically the level of abstraction of the original subject. Another criteria was the amount of saturation and related hue/tint throughout the sequences… these were essentially controlling aspect of the sound synthesis and other processes.

The prints from 3D scans are a third part of a process of translation: from computation, to 3D printing to print on paper. Did these passages reveal something unexpected in the final result?

In the last few years I become more and more interested in printing on paper as it allows to explore something that is not possible to explore with video (or at least not so easily): ultra-high-resolution.

When working with video you are generally limited by fixed resolutions, which can drastically limit the possibilities of visualising very large and detailed data sets.

These new works on paper reveal something else depending on which distance you observe them… from a longer distance they have an almost photographic feel, but as you get closer you can explore a very different granular quality, as they are made by hundred of millions of tiny spheres.

It is with this interaction that is possible to observe the two radically different aesthetics, the natural complexity vs the logic of the machine.

It is in the fine details that someone can get lost in a very different landscape than the one observed at a distance…

How important is the support for you? (I am here also referring to the paper you employed for printing)

The type of paper and printing techniques is crucial to the correct experience of the final work.

These images are almost like sculptures in the sense that they have a precise scale at which they need to be printed.

There has been a lot of research to find a good solution that allows readability from far away as well as very close, while still maintaining some physical presence of the paper.

In your work (including the series of Captives) you strive to reconstruct classic archetypes. What archetypes is the post-antropocenic era shaping?

My recent focus on nature and landscapes, both on videos as well as prints, is a reference to the modern tradition of landscape painting of the late 19th century, where nature becomes a point of departure away from representation. I am fascinated by how the subject of the landscapes became a vehicle to explore new aesthetics and visual synthesis.

On one side I am engaging with landscapes in a similar way to the one of the impressionist en-plein-air painter, however on the other bringing along a very different technological apparatus.

How has the relationship between man and machine being changing since you first embraced algorithms and robotics in your work?

Although exploring many different areas, my approach towards developing systems stayed quite consistent over the years… I am interested in creating instruments that can be used a bit like musical instruments, so they are essentially based on human interaction.

Usually in a project only about 30% of the time is used to develop a system, while the remaining 70% is used to explore that given system. So despite various generative strategies and automation concepts, my active interaction with the machine is where I find inspiration.

My artworks are essentially collections of results from such interactions.

Quayola, Vestiges, Charlot Gallery, Paris, 22.03 – 10.05.2018

images (cover) Quayola, «Vestiges», Galleria Charlot,installation view, photo courtesy: Anaelle Prost and Courtesy Galerie Charlot (1-2) Quayola, «Jardins d’été #2», 2016, One channel 4K video, 47’40’’, 2/6 + 1 ap, Courtesy Quayola and Galerie Charlot (3) Quayola, «Remains #L1_004-001», 2017,Print on Baryta paper mounted on aluminium, 33 x 50 cm, Unique, Courtesy Quayola and Galerie Charlot (4) Quayola, «Vestiges», Galleria Charlot,installation view («Remains, 2017), photo courtesy: Anaelle Prost and Courtesy Galerie Charlot (5-6) «Jardins d’été #2», 2016, One channel 4K video, 47’40’’, 2/6 + 1 ap, Courtesy Quayola and Galerie Charlot