In the 58th edition of La Biennale di Venezia the trend of paying greater attention to the interaction between visual arts and music, already present in previous editions, has been reconfirmed. The modus operandi that has seen the boundaries of contemporary art open up to other disciplines over the past few years is evidence that creativity cannot be restricted to one sector only; this issue is increasingly being felt in Italy, perhaps due to the differentiation between artistic disciplines, even at an academic level. The multi-sensorial exploration, historically connected to the search for the “total work of art”, produces interactions that, unfortunately, are not always remarkable.

To start with, this trend can be seen in the performance at the Lithuanian Pavilion, which won the Golden Lion, where a beach is recreated using sand, beach towels and performers wearing swimsuits who start singing in chorus while performing actions that are commonly seen at the seaside – some sunbathe, some apply sun cream while others play beach tennis. The reasons for the Jury’s choice were as follows: “the experimental spirit of the Pavilion and its unexpected treatment of national representation. The jury was impressed with the inventive use of the venue to present a Brechtian opera as well as the Pavilion’s engagement with the city of Venice and its inhabitants. Sun & Sea (Marina) is a critique of leisure and of our times as sung by a cast of performers and volunteers portraying everyday people.”

Although the performance uses a layout that is connected to music, apart from the specific features of the context and the type of execution, the choice of repertory is questionable. Even if the theme of the performance is meant to highlight the futility of actions carried out in our free time, presenting a multidisciplinary work, the final result is undoubtedly penalised by not giving equal weight to all the media employed. Composing the music, albeit “futile”, without following “traditional” canons, would have definitely been more effective. Perhaps contemporary art neglects what is happening in experimental theatre – to cite just one name among many of those performing in Italy, the Societas Raffaello Sanzio – where these types of actions have taken place for decades and the only thing that changes is the context. It is as if the national pavilion and the theatre were very different realities, or as if the theatre were never physically removed from the theatre itself. Awarding a “singing performance” without even analysing the music is clearly a reductive approach. Maybe those who are called upon to judge and assess these works should be less sector-based in terms of their cultural background, especially if they decide to give prizes to trends outside their area of expertise.

Despite the distance, now almost unbridgeable, between music and contemporary art – two sectors that examine each other from afar – their interaction manages to achieve really interesting outcomes only when the dialogue between different disciplines is addressed with equal purpose and knowledge.

In other words, interesting outcomes occur when one discipline is not subservient to the other. In this sense, the work presented at the Arsenale by the Lebanese artist Tarek Atoui is excellent. Atoui, constantly searching for unique sounds, has for many years explored new ideas with which to build not only physical instruments but also unconventional software. His installation consists of a series of small stages spread out across the space where different instruments are located: some benefit from kinetic interactions while others give resonance to strings and/or metal plates. Everything is then managed through a patch consisting of max MSP language, which visitors can see on a video screen and from which they can observe the general commands.

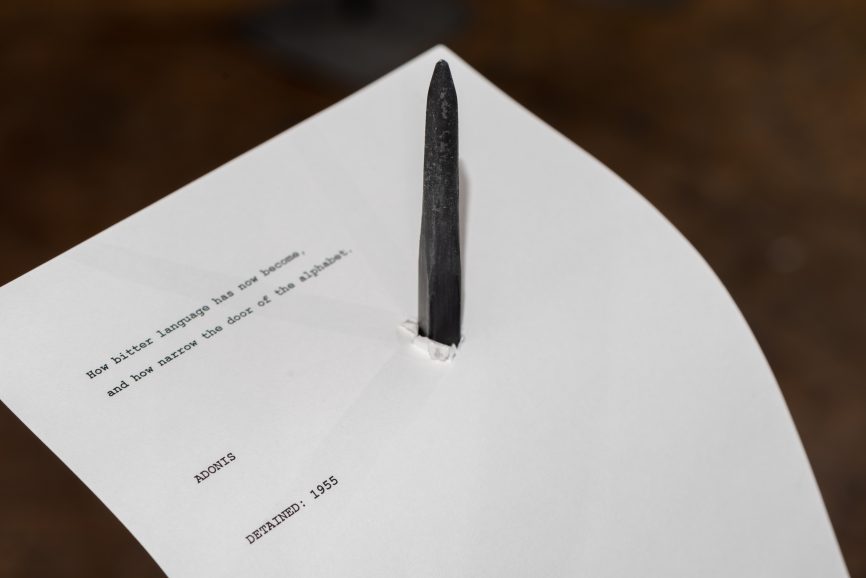

The work is both visually and acoustically elegant while, at the same time, being complex; the perceived result is moving and rewarding. These features can also be found, to some extent, in Shilpa Gupta’s large installation, For, in your tongue, I cannot fit, where her research into sound makes way for a “political” use of sound.

The installation consists of one hundred microphones with internal speakers that descend from the room thanks to an audio cable. The speakers broadcast verses from poets who were jailed for the content of their poetry or their political views, ranging from the seventh century to the present day.

At first, visitors listen to the sounds coming out of one single speaker and only subsequently hear the same sounds coming from the other ninety-nine speakers. It is an extremely evocative installation which, thanks to its extensive presence in the space, produces a perception of sound that makes a huge impact.

The work La Bùsqueda by Teresa Margolles is also of a political/social nature. Margolles, a Mexican artist, examines the brutality caused by narco-violence in Mexico from a feminist perspective. For this work, the artist recorded the sounds made by a train crossing Ciudad Juarez and transformed these into a low frequency sound which resonates in the exhibition space, causing a feeling of anxiety. The sound, using speakers, highlights several glass panels recovered from the centre of the city, mounted on independent wooden bases. These panels are covered with photocopies of torn posters, depicting the faces of women who have gone missing.

The work by Natascha Suder Happelmann for the German Pavilion is also one that aims to denounce injustice. The piece consists of an immersive installation which reconfigures the space of the German Pavilion using architectural elements, sculptures and sound, giving visitors a kinaesthetic experience. Six musicians and composers (Jessica Ekomane, Maurice Louca, DJ Marfox, Jako Maron, Tisha Mukarji and Elnaz Seyedi), using different styles and languages, contribute to the creation of this sound installation, a “tribute to whistle”. The music compositions are created from the sound of a whistle, an instrument used by migrants to try and attract attention when they fall overboard during their sea-crossing, but it is also the sound produced by the police force during raids. The sound has been developed with a large variety of rhythms and sounds. Each sound contribution has been recorded on eight channels and will be reproduced in constellations that are never the same by 48 speakers distributed on a scaffolding structure. Visitors interact with the piece by moving inside the Pavilion, contributing to the creation of an ever-changing sound.

The elaboration of “solid” sound is at the basis of Tomas Saraceno’s acousmatic work; in this case the artist presents visitors with the sound of the sixteen sirens located in the six Venice districts, which given the population notification of when the sea level rises and could reach the city within two or four hours. Acqua alta: En Clave de Sol speculates on what the sound of the floating city could be in one hundred years’ time, when Venice will be submerged as a result of rising sea levels. The recordings of the original sirens have been developed using data from stations tasked with controlling high water, checking tides and other data concerning pollution. This produces a six-channel composition broadcast in the Aresenale’s Gaggiagrande. The scores are stored in a display case, where it is possible to see the data which enable this composition to be created.

The employment of huge amounts of data is also at the basis of the new audio/video work by Japanese musician Ryoji Ikeda. Data-verse 1 (2019) is a large-scale projection that immerses visitors in a sea of acoustic and visual data. Drawing from huge scientific data reservoirs, extrapolated from institutions such as CERN, NASA and the Human Genome Project, Ikeda has developed mathematical compositions to process and re-elaborate raw data in digital “verses”, which explore representations of space, from elementary particles to the infinite space of the universe. This is an extremely effective and sophisticated work that engages visitors, projecting them into a dense “digital” dimension. A completely different strategy is the one implemented this year by the Japanese Pavilion with the work Singing Bird Generator. When entering the pavilion visitors are met by a large air chamber in the shape of a circular seating arrangement, where they are invited to sit down. A series of tubes connected to several wind instruments emerge from a hole in the seating. The movement of visitors inside the air chamber actives the transmission of compressed air to the instruments which, using mechanical fingers, produce random notes. This is a deja-vù work, a legacy from artists like Max Eastley, who started creating installations that utilised wind from the 1970s, or more recent pieces, definitely more complex in terms of composition, by Andrea Valle and Simone Pappalardo.

The use of sound in contemporary art, which I cannot call “sound art” due to the rhetorical and already historicised meaning of this term, is a positive development in the way it has made a place for itself among current trends. The approximate way in which these themes have been tackled, however, is definitely disappointing. Criticism in contemporary art cannot afford to be so sector-based when assessing something that is in continuous evolution. Obviously, it is impossible to remain up-to-date with all levels of creativity, but it is also true that the good practice of not writing about things about which we have little or no expertise has long been discarded and, above all, the habit of researching something and gathering information before making a judgment has been lost. This attitude generates many false myths and, more importantly, impoverishes the evaluation of the research carried out by artists.

Biennale Arte 2019. 58. Esposizione Internazionale d’arte, Venice, 11.05 – 24.11.2019

images and videos: (cover 1) Trek Ataoui, at the Venice Biennale 2019. Performances during the opening of the Venice Biennale, May 9–10, 2019, 6pm (2) video vimeo Tarek Atoui, «The Spin», 2016, Instrument: 24 ceramic pieces, between 10 and 75 cm, Central international exhibition, Arsenale (3) Shilpa Gupta1, «For, In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit», sound installation with 100 speakers, microphones, printed text, and metal stands; site specific; 2017-18; Commissioned by YARAT Contemporary Art Space and Edinburgh Art Festival; Courtesy: The Artist and GALLERIA CONTINUA, San Gimignano / Beijing / Les Moulins / Habana | Photographer: Pat Verbruggen (4) Photo Caption: Shilpa Gupta, «For, In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit», sound installation with 100 speakers, microphones, printed text, and metal stands; site specific; 2017-18; Commissioned by YARAT Contemporary Art Space and Edinburgh Art Festival; Courtesy: The Artist and GALLERIA CONTINUA, San Gimignano / Beijing / Les Moulins / Habana | Photographer: Johnny Barrington (5) Video, Tomas Saraceno, «Acqua alta: En Clave de Sol», installation at the Gaggiandre of the arsenale, central international exhibition, Venice Biennale 2019 (6) Video Ryoji Ikeda, «Data-verse 1», 2019