From a critical standpoint, XX century art has been divided in two major groups: avantgarde and tradition. But in the light of the great transformations occurred, it appears more reasonable to distinguish between experimental art that focuses on the idea of research (of materials, techniques, processes, methods, ideas), and art that doesn’t present elements of experimental projectuality. We are now going to offer to the reader some exemplary stories of some of the protagonists of the Futurist movement and of their motivations along with some of their works, although they would obviously deserve a much more detailed treatment.

The Great Futurist Big Bang (1909-1944)

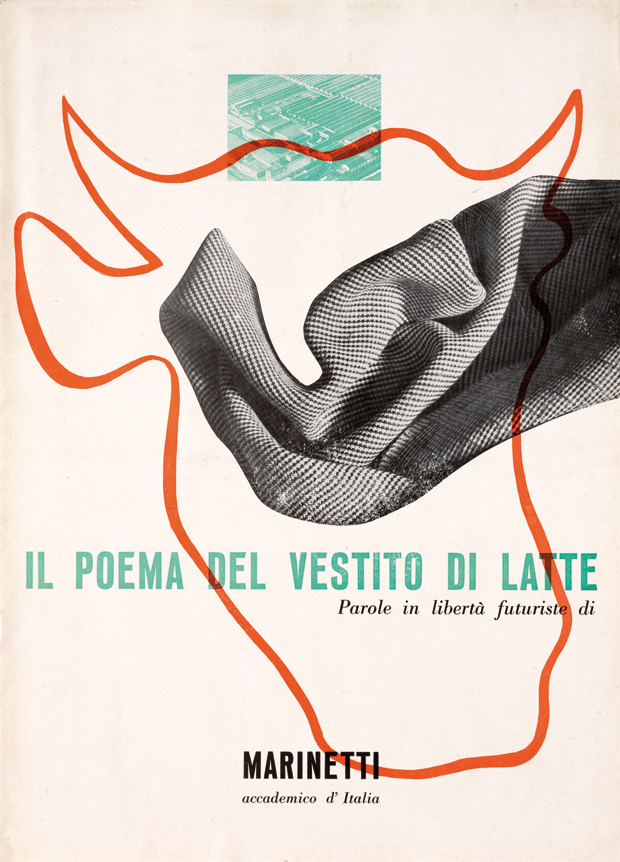

The founder of the Futurist movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, is a complex and eclectic figure of artist, poet, thinker, publisher, political agitator, and patron of the arts. His ideas were quite ahead of his times, and he was able to use mass media to turn project into artifact (Marinetti will publish his manifesto before any futurist artist produced a single work of art). He could cause scandal making a name for himself and for the movement with catchphrases that get fixated in the mind («Let’s kill the moonlight!» or «The war, world’s only hygiene»). He is the restless organizer of shows that easily become performances and demonstrative actions, some of which turning into fights that eventually hit the news. He is in touch with the great minds of the European and international cultural scene, with some of them aspiring at meeting him (from Ezra Pound to Picasso, from Majakovski to Stravinski, from Apollinaire to Borges).

Futurism has a pars destruens—certainly its best known facet—whose goal is to overthrow antiquated culture that is incapable to give form to the great ongoing transformations. Its very cult of violence mostly serves to create scandal and to make a tabula rasa of the past. Futurism’s pars costruens, instead, articulates in a copious output of inventions spanning from poetry, painting, sculpture, and architecture, to applied arts, and from music, film, and photography, and from gastronomy, flight, publishing, to theater, and much more. As the bases of futurist poetics mirror the mechanisation of the world operated by the industrial revolution, the stereotypical image of Futurism reduces it to a mere apology of ‘movement’, ‘dynamism’, and ‘speed.’ A different interpretation of futurist poetics focuses, instead,h on the instability and on the tensions of moving forms. Futurist painters aim at demonstrating that life is in constant evolution, an ever-changing process, and that «form does not exist, as form pertains to what is still, whereas reality is in movement…that is why only the continuous changing of form is real».

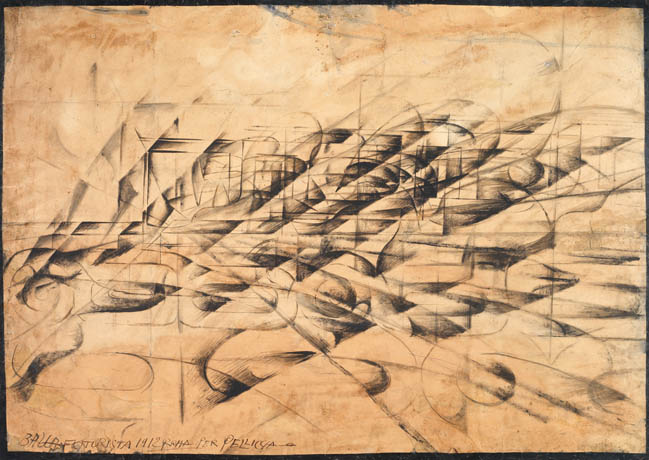

Simultaneity, fragmented reality, dynamism are all part of our visual culture. Giacomo Balla—whose art has been the protagonist of recent New York Sotheby’s auction, scoring over eleven million dollars for the painting Automobile in corsa (1913) —devoted a study, methodical and meticulous like that of a scientist, to the cars passing by via Veneto in Rome. In Balla’s studies—that in some sense can be likened to Leonardo da Vinci’s studies, the figures of cars become more and more abstract up to the point of their disappearance. Eventually they give way to the vanishing points of the movement of penetration of the space in the car. The method followed in a drawing like this is that of scientific experimental inquiry. This method is aimed at giving pictorial or sculptural shape to a concept, that of the mutability of the form of the world. In so doing, such a method provides artistic languages with aesthetic solutions that over time become part of our visual culture.

If Cubism prompts us to consider a given representation from multiple points of view, suggesting that there is no just a single reality but a multiplicity of them that depends exclusively from our point of view, Futurism, in a more advanced fashion, teaches us that reality undergoes a constant change. This change can be described only as a dynamic process in space-time, as a complex system made of fragmented images representing the granularity of such a complexity. In 1915, Balla and Depero authored the famous manifesto Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe—after which the recent New York Guggenheim exhibition is named—and pushed things forward. By designing mobile «plastic complexes» gyrating one or more pivots, and plastic complexes breaking down into volumes, layers, or by successive transformations, the two artists laid the foundations of a new art, relinquishing once and for all the traditional form of a painting and opting for the de-materialisation of its form in the space. «We will give skeleton and flesh to the invisible, the impalpable, the imponderable and the imperceptible», wrote the authors of the manifesto. Unfortunately, a notorious flaw of Futurism lies in the contradiction between its high theoretical capability and its similar inability to give visual shape to its own theories. This is the very reason why many futurists’ ideas found their actual realisation only in the decades following the age of Futurism and quite often once its experience was over. Also, this occurred thanks to those artists that were formed and reached their maturity in those years. In a sense, it is as though Futurism were partially more theoretical than practical. Still, it remains obvious that the time for actions follows the time of theory and projects.