“I imagine their shapes, just by listening to them. Just as you hear my voice now. I can’t see them, but I hear them constantly. I recognise them by the sound they make. They seem to be playing just for us. All together, they become music, like a symphony (…)”

Is it possible to understand a machine only by listening to the noise produced by the buzzing of its blades? Becoming intimate with technology, indulging this symbiotic relationship with one’s own body? This question has become the inspiration for the creation of the show Phoenix – Process of Creation in Situation of Conflict by Éric Minh Cuong Castaing, French choreographer, and Mumen Khalifa, Palestinian dancer living in a Gaza refugee camp, presented this year at the Romaeuropa Festival.

Castaing and Khalifa began discussing the idea, leading them to develop the foundations of this show, two years ago. The delicate political situation in Palestine did not allow Castaing and Khalifa to meet in person. They opted instead – in an almost prophetic way when considering these difficult months – for an exchange via Skype, overcoming almost insurmountable geographical and cultural distances.

The sound element in Phoenix is fundamental. Whether it is silence, threatening buzzes, voices talking or the stage creaking, the sound element fills the scene and is the protagonist: it becomes a vehicle for messages that travel from one part of the world to another via the internet, and from humans to machines through a language consisting of silences and mechanisms.

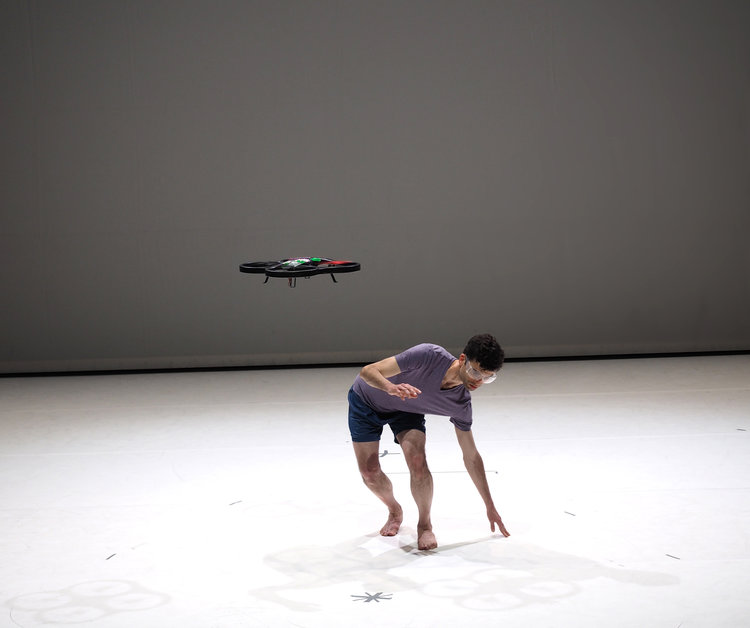

The drones are the show’s protagonists, together with the dancers: remote-controlled flying machines, similar to tiny alien spaceships, which can be experienced in various ways depending on the location – in Europe they are used as toys while in Palestine they are a means of surveillance or spell death. The show revolves around this difference in perspective – how drones can be perceived by the body and the mind. Khalifa, in Gaza, lives and sleeps with the constant buzzing of drones flying over the houses. They became his lullaby and a part of his body and mind. By only the sound they produce he knows whether they are carrying bombs, death, guarding the territory or transporting objects. In an inexorable process of humanisation of the machine, he tries to imagine their feelings: are they sad? Happy? Angry? Everything depends on their sound, which becomes a voice.

Together with Castaing, on the other side of the world, the dancers have started a very slow operation to sensitise the body to the presence of drones. Their bodies are in constant dialogue with the machines, which glide over them at close range. Paradoxically, drones and humans thus enter into an intimate relationship and become like lovers, in a constant exchange based on movement, voice, glances directed at each other and commands. In other words, the drones assume a scenic presence, a personality.

The show does not aim to stage the fear that drones can arouse in reality, but the connection established with humans through their vibrations, sound and the air that they displace. Dancers become antennae, sensitive elements that connect to the drone with all parts of their body, following minimal impulses. This produces a perceptible tension on stage and the audience, in turn, connects to the dancers’ bodies through their imagination.

The art of contemporary dance meets the art of resistance.

Individual viewer streaming gives a semblance of exclusiveness: the dialogues, the glances at the camera, the pauses of deafening silence pierce the screen and seem to be uniquely directed at the observer. The impression created is of being transported into another dimension, a room where several geographical places can be found simultaneously.

Chiara Amici

images: (cover 1-3-4) BACK ONL(Y)NE for Phoenix- Process of creation in situation of conflict by Éric Minh Cuong Castaing and Shonen, Digitalive. Romaeuropa Festival 2020, still from video (Flavia Costanzi, Francesco Pacifici, Francesca Paganelli) (2) Éric Minh Cuong Castaing(2) Phoenix shonenviadanseSL31c-1