…Luca Zaffarano continues his dissertation on the Projections by Bruno Munari that took place on June the 3d, within the international day-study that Museo del Novecento in Milan has dedicated to the artist within the exhibition Munari Politecnico», curated by Marco Sammicheli and Giovanni Rubino.

Continuous focus Projections.

The first exhibition at which Munari presented the continuous focus slides was held in Milan at the Galleria del Fiore in May 1955, even though (for the sake of precision) the magazine «Domus» had already published a photograph in February 1954 of a sample of a slide that had been predisposed for multi-focus projection[1]. Upon invitation of the Milan exhibit, it was announced that the artist «will project his recent compositions of fixed colours and colours as variable as day and night at two continuous focuses».

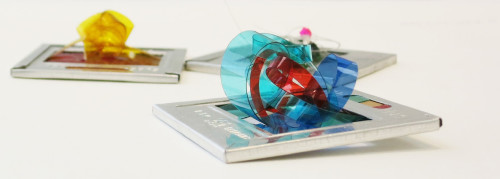

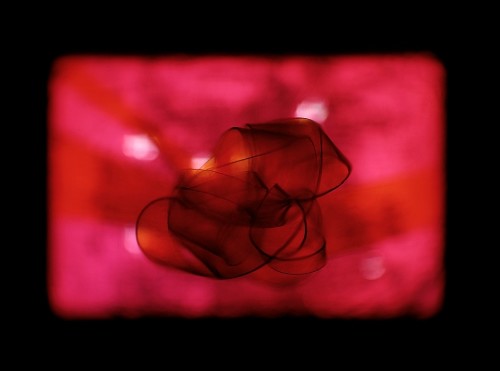

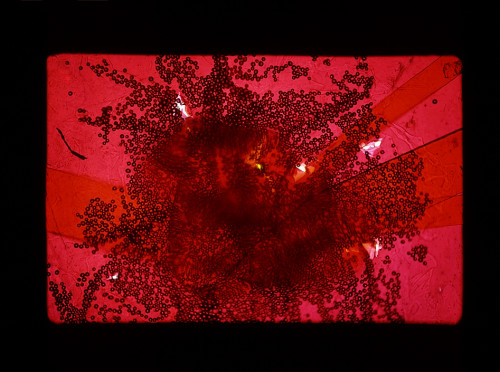

It can be observed in the double photographs of a multi-focus slide from 1952 that the composition was created with layers of yellow plastic material on a red background. A tangle of twisted film like a kind of cloud sticks out of the slide. The development in the space of the micro-composition allows for more than one single focus of the image, making it possible to create images that are quite different from one another. The gradual shift of focus allows for a virtual motion, a kinetic and chromatic effect which – even with it brief duration – can be delineated as an abstract film.

The first image directly recalled the ambiguous and mathematical shape of Concave-convex suspended in an evanescent atmosphere of an unfocused colour. The second image recalled the pattern of a very organic composition. The constant motion of the focus shifting from the first to second image made it possible for the artist to create a painting with a cinematographic system.

In 1959, Munari designed a boxed game for the Danese Milano Company which was given the title Box for direct projections. In the product’s leaflet Munari specified that the package contained: «all the necessary material to make small transparent coloured compositions to be projected (like the ones Munari had projected in New York and Stockholm, in museums and private residences) – a new visual art technique».

You can see one of these works from the Vodoz-Danese Milano in the photograph below and note how the composition obtained by overlapping the coloured and transparent material sticks out from the slide’s frame.

Cinematographic, polarized painting and luminous boxes

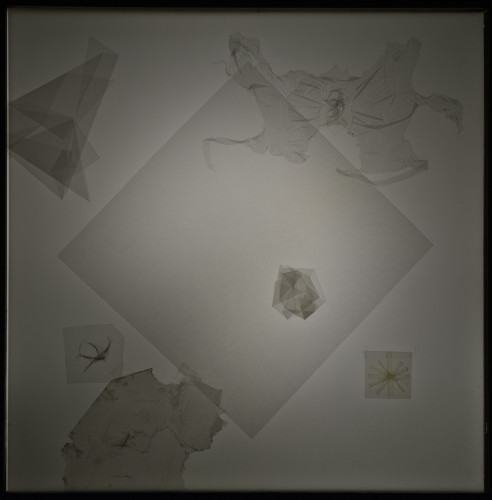

Munari created yet another variation in 1952-53 by rotating a Polaroid filter in front of a projector’s light bulb. The polarized lens has a microscopic crystal structure that functions as a filter for those frequencies that do not cross the material from a perpendicular angle. Therefore, an infinite number of continuous variants can be obtained by moving the filter in front of a projector’s light bulb.

«Painting can even disappear as long as art remains», Munari wrote in the 1961 Bompiani Literary Almanac.[2] Munari would continue with his research throughout the 1960s, by first reproducing the luminous boxes of polarized painting denominated as Polariscope and later producing short experimental films that illustrated certain results of the experimentation in the perceptive sphere.

This research sprung from the exploration of the possibilities offered by a Polaroid filter. The film produced by the American company is made up of transparent foils with the characteristic of filtering some components of the light spectrum based upon the light’s angle. Munari studied this material thoroughly in order to identify its characteristic properties and to understand how this industrial product could be used for visual communication and, obviously, with what kind of aesthetic results.

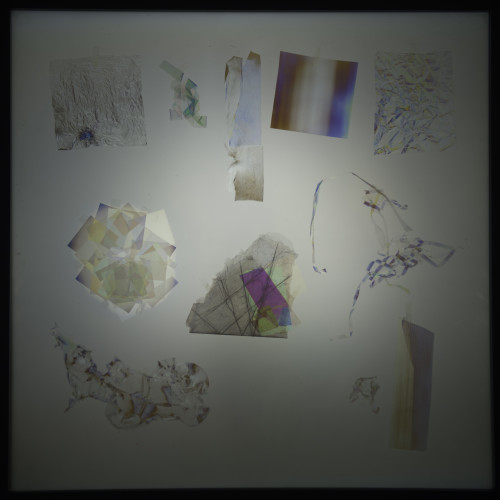

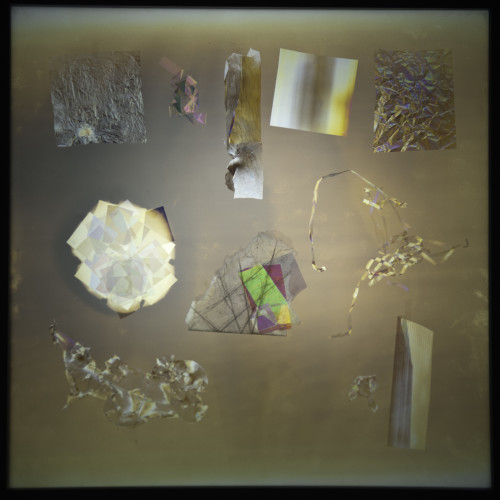

The effect of the Polaroid filter becomes visible by placing colourless material between a «sandwich» of filters, specifically through the rotation of the one closest to the observer in order to create a virtual motion of the composition created by the artist. Some of these luminous boxes denominated Polariscope have only one Polaroid filter on the bottom and a switch located within the work to turn the neon light on. The composition, realized with the material fastened onto the bottom (a bottom made with a Polaroid sheet) appears exactly like the way it is represented in image 14: rather unattractive and barely convincing. The spectators were given a transparent disc – the second Polaroid filter – and invited to bring it to their eyes, rotating it as they pleased while observing the work. The wonder was often revealed by a sudden explosion that left no room for doubt as to the pleasure of the experience.

By taking a closer look we can see that two crucial traits of the way art and its social usefulness are interpreted are found in this simple experiment. On the one hand, the surprise factor and the spectacular nature of the experiment act as a powerful stimulus for the purpose of familiarizing the public with the poetics of an extremely innovative and unconventional artist. On the other hand, the pictorial composition, made with simple material (almost from nothing) comes from the action of the spectators who are actively involved in the process of shaping the image. The artist is given the task of creating a framework, a work space and well-defined rules (a certain kind of material, a given composition, rules of use) while spectators are handed the task of creating a painting (at will or for pure aesthetic satisfaction) suited to their personal sensitivity without any pressure or imposition. By rotating the outermost filter for 360°, countless nuances of the light’s dispersion can be obtained as it crosses the colourless plastic material and the two layers of the «sandwich’s» polarizing filter.

Munari had never been a painter in the traditional sense of the word. He had always been a painter in his own way, through unusual methods and approaches with an open mindedness towards technology and novelties.

A multiplicity of images

Painting is no longer an image, but a variety of images that are no longer static. These experiences offer us a chance to reflect upon the shape of the world, a dynamic world in constant evolution that can only be represented and understood through the poetic staging of this very continuous transformation. If reality never rests, to paraphrase Futurist painter Boccioni, painting – once it has been drawn out of the frame of a painting – becomes an immaterial space that can be visited and crossed; it becomes an environment of light, a visual, spatial, total and involving experience.

In Munari’s art – as critic Carlo Belloli has pointed out – «it is rare that on object or image of his stands still for long: everything moves, or through the air, or due to the optical effect or any other possible stimuli[3]».

The idiom’s domain by definition is the triple dimension of colour-space-time. Luminous environments are created through the use of light and projection and virtual chromatic movements are created through the rotation of polarizing filter.

The re-proposal of chromo-kinetic painting, theorized as far back as the 1920s by exponents of the Bauhaus school, finds a sophisticated reinterpretation in Munari’s luminous environments from the early 1950s. Works by the Milan native artist anticipate many works which, beginning with the second half of the 1950s, were variations on a theme: from Frank Malina’s electropaintings, luminous mobiles by Italy’s Nino Calos and the chromo-kinetics of Gregorio Vardanega and Martha Boto to the recreational, civic and collective experiences of the Parisian group G.r.a.v. (Groupe de Recherce d’Art Visuel), the works of Julio Le Parc, Heinz Mack, Nicolas Schöffer and the many other international protagonists of kinetic movements.

«If a piece of cellophane is placed between two Polaroid discs like a sandwich and you observe it against the light, you can see that the colourless cellophane has taken on various colours. If you rotate one of the two Polaroid discs slowly, the colours change into complementary colours. This is a simple phenomenon of physics to study. It is all about knowing: how many colourless plastic materials are there that give off colour? Which colours to they give off? How can they be used? How does the colour vary? Can faded colours be obtained..or colours by geometric sectors? Which angle do you need to give a certain plastic material in order to obtain the colour you want? How can all of this become the object of visual communication, information and expression? How can these materials be altered in order to obtain light sensitivity? What kind of texture can you create? What happens with the colour?»[4]

Among the main expositions in which Munari presented his polarized projections, we would like to mention the exhibits held at the Stockholm Museum of Modern Art in 1958, at Tokyo’s National Museum of Modern Art in 1960 accompanied by electronic music composed by Toru Takemitsu, at Padua’s Teatro Ruzante and the halls of «Gruppo N» in 1961, at the 1966 Venice Biennale in a solo hall and at New York’s Howard Wise Gallery that same year, at the «Campo Urbano» group exhibition in Como in 1969, at London’s Hayward Gallery in 1970 as part of the «Kinetics» group exhibit and many more.

[1] Ibid.

[2] Achille Perilli, Fabio Mauri (edited by), Inchiesta: morte della pittura?, in «Almanacco Letterario», Bompiani, Milan 1961, Bompiani, Milan, 1960

[3] Carlo Belloli, Designers italiani. Con Bruno Munari continua la galleria dei personaggi che hanno inciso sull’evoluzione del costume artistico italiano [The gallery of characters who influenced the evolution of Italian artistic tradition continues with Bruno Munari], in «Ideal Standard», January 1965 numbers.1-2, Milan

[4] Bruno Munari, Design e comunicazione visiva [Design and visual communication], Laterza, Bari, 1968.

The international day-study dedicated to Bruno Munari, organized in concomitance with the show Munari Politecnico» was curated by Marco Sammicheli and Giovanni Rubino. The event was sponsored by the Massimo & Sonia Cirulli Archive (New York) with the participation of Pierpaolo Antonello (University of Cambridge, UK), Zvonko Makovic (University of Zagreb, Croatia), Matilde Nardelli (UCL, UK), Maria Antonella Pelizzari (NY Hunter School, USA), Jeffrey Schnapp (MetaLAB, Harvard, USA), Margherita Zanoletti (Cattolica University, Milan, Italy). The Projections were the object of a brief conference closing the day.

Images

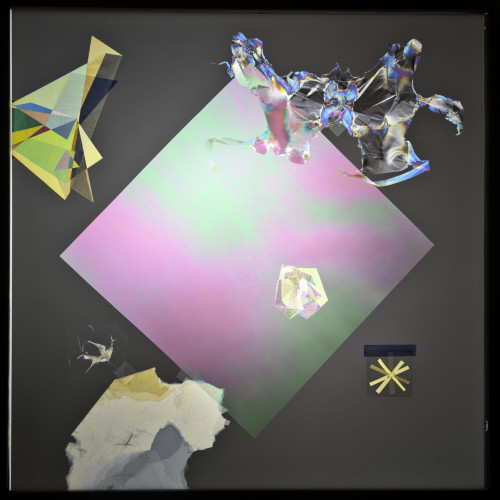

(1) Bruno Munari, slides (with extrusion of plastic material) for installation of dynamic painting throughout a projection with variable focus, 1952, collection of Jacquelin Vodoz – Bruno Danese Foundation, Milan, photo by Arttribune (2 e 3) Bruno Munari, two images obtained by the same slide for Multifocal Projection, 1952, collection of Jacquelin Vodoz – Bruno Danese Foundation, Milan, photo by Roberto Marossi (4) Bruno Munari, slide for Proiezione Multifocale [Multifocal Projection], 1952, collection of Jacquelin Vodoz – Bruno Danese Foundation, Milan, photo by Roberto Marossi (5) Bruno Munari, a moment of the polarised projection on the façade of Palazzo Ducale’s Palace in 1953 (Sassuolo, Italy) within the show «Bruno Munari. Fantasia Esatta», curated by Miroslava Hajek and Luca Panaro, Festival of Philosophy, Modena, Italy 2008 (6 e 7) Bruno Munari, two moments of a Polariscop (Sixties), collection of Colossi Brescia Gallery, Italy, photo by Pierangelo Parimbelli (8 e 9) Bruno Munari, two moments of a Polariscop (Sixties), Giancarlo Baccoli’s collection, Brescia, Italy, photo by Pierangelo Parimbelli (10) Bruno Munari, Proiezione diretta [Direct Projection], collection of Jacquelin Vodoz – Bruno Danese Foundation, Milan, photo by Roberto Marossi.