On the occasion of the «Munari Politecnico» exhibit hosted at Milan’s Museum of the 20th century (Museo del 900) curated by Marco Sammicheli and Giovanni Rubino, an international study day dedicated to Bruno Munari was held on 3 June 2014. This special day was sponsored by the Massimo & Sonia Cirulli Archive (New York) with the participation of Pierpaolo Antonello (University of Cambridge, UK), Zvonko Makovic (University of Zagreb, Croatia), Matilde Nardelli (UCL, UK), Maria Antonella Pelizzari (NY Hunter School, USA), Jeffrey Schnapp (MetaLAB, Harvard, USA), Margherita Zanoletti (Cattolica University, Milan, Italy). The Projections were the object of a brief conference closing the day and Arshake is pleased to published it, divided in two parts.

Bruno Munari. Painting with light.

If I have seen further, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants Isaac NewtonArtist Lazslo Moholy Nagy (1895 – 1946) published Painting Photography Film[1] in 1925, an essay that soon became famous for being the eighth volume of a series edited by the Bauhaus School founded in Weimer by architect Walter Gropius and such artists as Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. In the chapter The domestic pinacotheca, the author clearly states his opinion by hypothesizing on several possible approaches to art in the future: «It is probable that the future development will attach the greatest importance to kinetic projected composition, probably even with the interpenetrating beams and masses of light flowing freely in the room…». He adds, in his attempt to delineate the approaching future technology: «Aside from this, there is also the possibility of collecting slides just as we collect records.» Moreover, the Hungarian artist made broad reference to the possibilities offered by the latest technological development in regards to the reproduction of paintings, photographs and experimental cinema. The step towards projected painting had not yet come to pass, even though in the 1920s, authors such as Thomas Wilfred (1889-1968), Kurt Schwerdtfeger (1897 – 1966) and Lazslo Moholy Nagy (1895-1946) had created mechanical abstractions thanks to the modulation of different sources of light.

It is very probable that the theoretical essay by the Hungarian artist was a determining factor in the formation of the aesthetic thought of Bruno Munari (1907-1998) precisely because the Milan-born artist found in this essay the expression of a shared interest in a total dematerialized environmental art in which painting was no longer static, taking on shapes that were completely dynamic. Regarding the issue of installations and lighting environments, Munari gave an interview towards the end of his life in which he related the dissatisfaction with the static way in which Futurism had treated motion with the necessity to experience «a material that takes shape in space, making something that had been previously unknown visible; this could even be a beam of light.»[2]

Works by the pioneers of the European Avant-Garde movement during the 1920s and 30s were a departure point for Munari in his development of immaterial painting (Direct Projections, 1950) that was dynamic instead of static (Variable Focus Projections, 1952), interactive and without mechanical repetition (Polarized Projections, 1952 and Polariscope, 1960s). We will analyse these explorations by showing how their succession in time is linked to the development of an aesthetic and theoretical thought which, like the lighting environments, reaches one of the most innovative points of the artist’s creativity.

Direct Projections. The dynamism of portable painting.

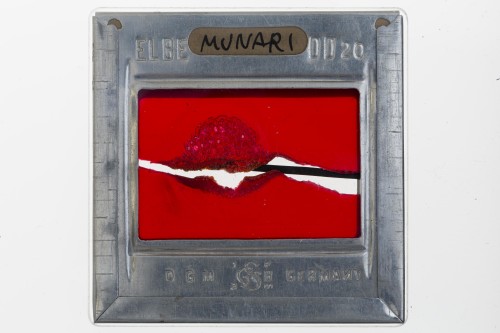

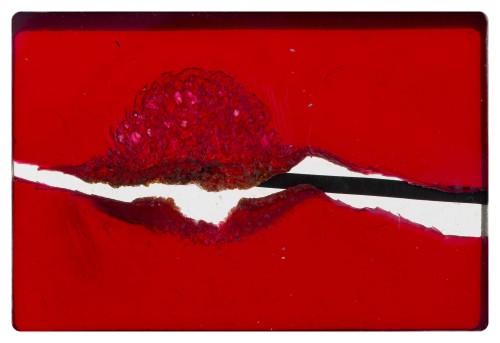

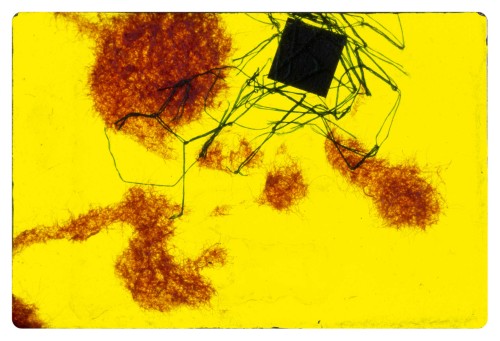

Beginning in 1950, Munari created projections of compositions built with «transparent, semi-transparent and opaque materials, violently or delicately coloured with plastic materials that are cut, ripped, burned, scratched, liquefied, engraved, pulverized; with animal and plant fabrics, artificial fibres, with chemical solutions.»[3] These materials were placed within normal slide frames. The projection obtained from micro-compositions removes the physicality of the works while light and large-scale projections restore a spectacular monumental dimension.

Munari explained that a cupola can be frescoed with a small slide or that a large exhibit can be carried in one’s pocket. The author imagined a setting for this new type of art work in the context of designing a modern home: «We can suppose that the house of the future will have minimum living space in relation to maximum comfort with minimal upkeep effort. Tape recorded music already works in this environment, but nothing has yet been done for the visual arts (except for photographic reproductions of works from the past).»[4]

These are all miniature works, micro-compositions visualized through a projector. Large luminous environments can be outfitted if the projector’s bulb is bright enough. «They are not coloured photographs, they are direct projections of material», the author clarified in the pamphlet that announced their first presentation in Milan in 1953. These pictorial compositions were projected for the first time in October 1953 at the Milan-based Studio B24 of architects Brunori, Radice and Ravignani.

In the article written in 1954 about Direct Projections for «Domus» magazine, Munari proudly observed that the obstacle of 100 paintings is only 5 cm x 5cm x 30cm and so collectors could now conveniently carry their gallery around with them, project the paintings on the walls of a hotel room in sizes that could range from a few centimetres to a few metres.

Among Munari’s various goals, there was also the one of introducing artistic production to a private cultural dimension, in an attempt to find a way to create exchanges between art, experimentation and the public that included elements of entertainment to make them fun and spectacular. This was a pre-condition for involving spectators. Munari also stated in the article: «Modern life has brought us music on records […] now it gives us projected painting[5]», emphasizing how necessary it was to find suitable solutions – even to problems of a technological nature – in order to bring art and everyday life closer together in such a way that the enjoyment of a work can take place with the means that are best suited to contemporary idioms.

After having made their debut in Milan in 1953, Munari proposed Direct Projections later that year to the large studio of Gio Ponti and associates. The following year, the artist presented his light paintings in New York; first to Leo Lionni’s studio and later at the solo exhibit in 1955 at MoMA, which he shared with American graphic artist Alvin Lustig.

[1] Laszlo Moholy Nagy, Pittura, fotografia, film [Painting Photography Film], Einaudi, Turin, 1987

[2] Interview with Bruno Munari by Miroslava Hajek, in «Bruno Munari Instalace», Catalogue of the exhibit at Klenova Castle, 1999

[3] Bruno Munari, Le proiezioni dirette di Bruno Munari [Direct projections by Bruno Munari], in «Domus», number 291, Milan, February 1954

[4] Bruno Munari, Codice Ovvio, Einaudi, Turin, 1971

[5] Bruno Munari, Op. cit., Milan, February 1954, Milan. This statement was copied by Victor Vasarely who would make reference to it in Notes for a Manifesto, written for the occasion of the historic «Le Mouvement» exhibit held at Denise Renè’s Parisian gallery in 1955.

Images

(1) Bruno Munari, slide for Proiezione diretta [Direct Projection], 1950, collection of Jacquelin Vodoz – Bruno Danese Foundation, Milan, photo by Roberto Marossi (2) image obtained by projecting the slide of fig. 1, photo by Roberto Marossi (3) Bruno Munari slide for Proiezione diretta [Direct Projection], 1950, collection of Jacquelin Vodoz – Bruno Danese Foundation, Milan, photo by Roberto Marossi (4) image obtained by projecting the slide of fig. 1, photo by Roberto Marossi (5) Bruno Munari, example of Proiezione diretta [Direct Projection], 1950, collection of Jacquelin Vodoz – Bruno Danese Foundation, Milan, photo by Roberto Marossi (7) Bruno Munari, example of Proiezione diretta [Direct Projection], 1950, collection of Jacquelin Vodoz – Bruno Danese Foundation, Milan, photo by Roberto Marossi.