Arshake is pleased to publish the text by Giovanni Festa that accompanies Ecce Homo, installation by Cristian Rizzuti in the spectacular frame of the Archives of Bank of Naples Foundation.

Focusing on the figure of the dead Christ by artists from all ages implies, on the one hand, dwelling on the scandalous humanity of Jesus while, on the other, emphasising how even the darkest moment is, in reality, a ritual moment of transition. The reclining figure always seems to be waiting for breath, a positive soteriological shock that will revive it, that will bring it back to life.

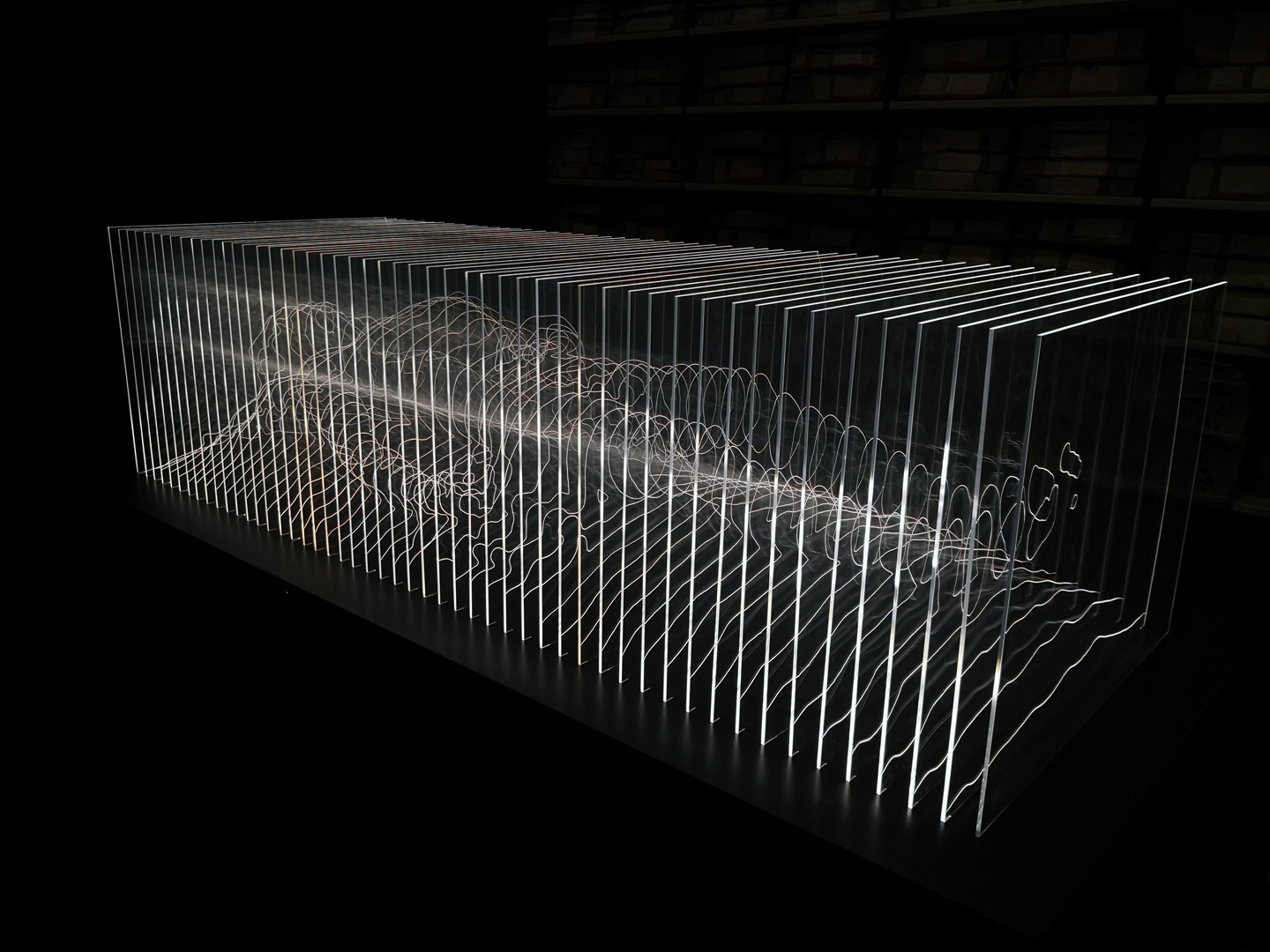

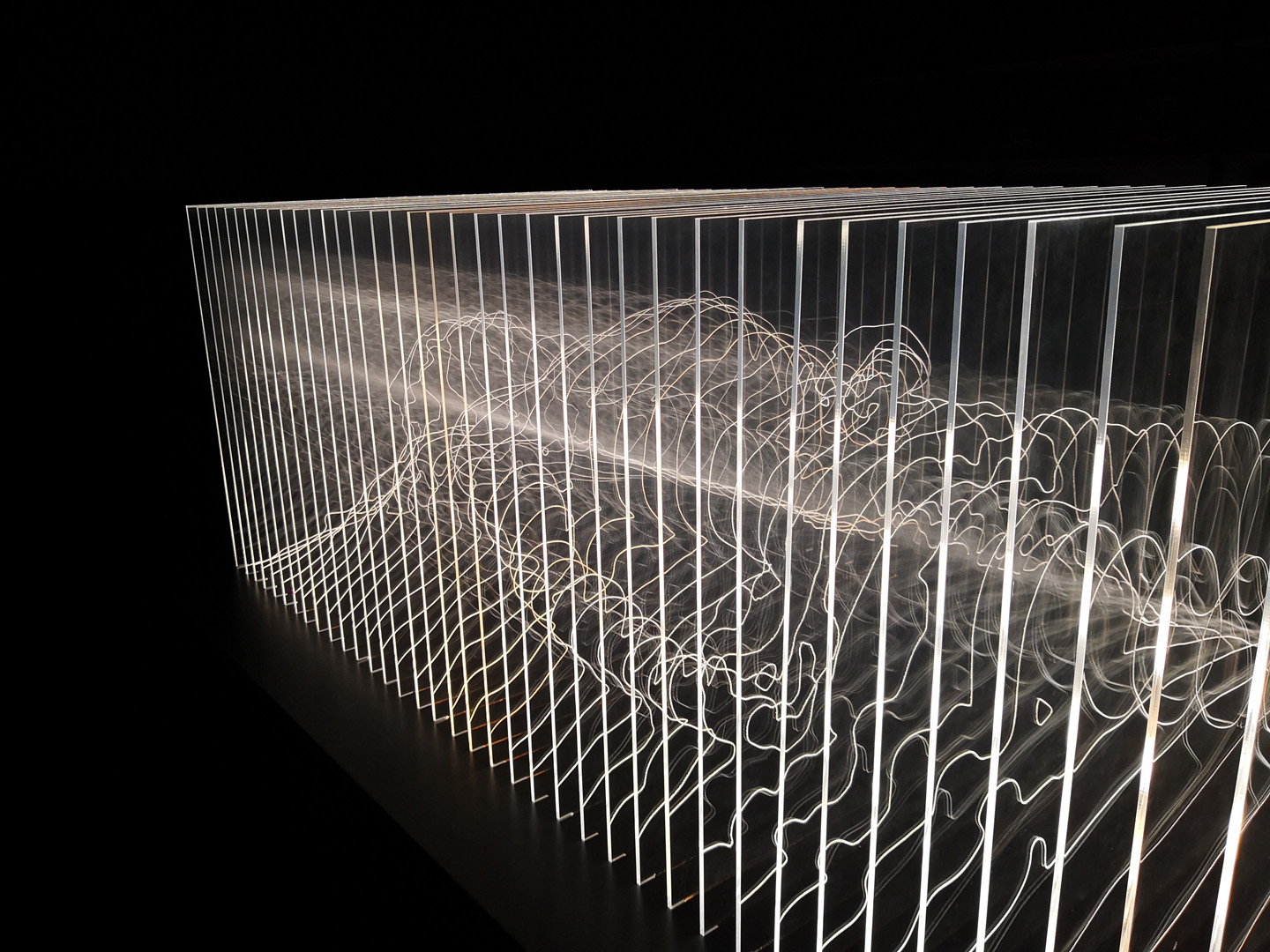

Cristian Rizzuti’s Ecce Homo is an artwork which dialectically stretches, like an arch, between the past (the history of art, the iconography of the Saviour’s reclining body, matter that becomes aura, a luminous trace) and the future (the laser engraving technique used on the support, the choice of support itself – plexiglass, LEDs and the use of light as tangible material creating and defining form, the three-dimensionality that is both tangible and completely visible). At the same time, past and future form an image that is politically present (and therefore also scandalous, if scandal is understood as what happens when sacred iconography adopts the forms of the present, appropriating them while, at the same time, remaining immersed in and contaminated by them).

The genealogy of this recumbent Christ, immersed in the parallelepiped that simultaneously imprisons him and gives him form is clear. On the one hand, there is the perspective of foreshortening in Mantegna’s Dead Christ, which places spectators before a figure that offers no point of support and seems to collapse before them or move against them, like a prow. Then, on the other, there is Sanmartino’s Veiled Christ, whose movingly clinging veil is replaced here by light which assumes the intensity of spiritual energy. Sculpting light might, first of all, represent an attempt to do this, to take an X-ray of the vital principle and try, by deconstructing the body, to show the fibres of the soul which simultaneously consist of the tangible body and its absence. As a result, past and future, cultic image and technological image are all intertwined.

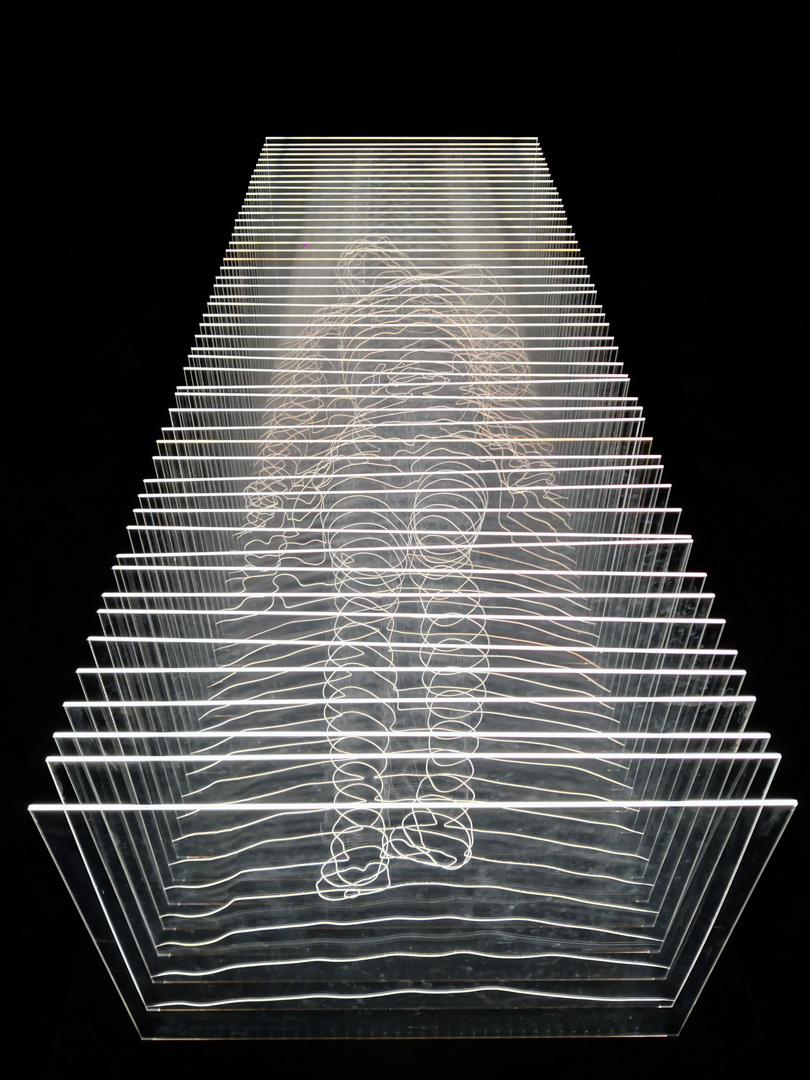

The cultic image is about making present through absence. Seeing the soul through the body signifies experiencing its aura. This is an interesting and important concept! The term derives from Greek, meaning breath or breeze, and then becomes the opportunity, on the part of a phenomenon, to be able to look at the person observing it and return their gaze. In fact, it is easy to imagine, as we walk around Ecce Homo, that this body of light is looking at us. It then becomes, in Benjamin, that singular interweaving of space-time defined as “the unique appearance of a distance however near it may be.” It is therefore linked to the cultic dimension of the image. Ecce Homo transposes the cultic characteristics of the work of art – uniqueness, authenticity, originality, transmissibility, work contemplated in situ by the viewer – into the final era of technical reproduction, spectacle and simulacra. At the same time, it turns one of the cultic images par excellence, that of the reclining Christ, into a simulacrum. Moreover, Ecce Homo, as the emanation of an aura, imprisons us, capturing our gaze as we observe it.

The technological image: the figure, and it is as well that we bear this in mind, is to be found in a case, a kind of space-time crypt-capsule. And this brings to mind a figure immersed in cryogenesis, a curious faith-based technology where the body is put to sleep, only to be awakened in the future in a labyrinthine moment of suspended time. In DeLillo’s novel on the same subject, we are invited to think of cryogenesis as a metaphysical condition of survival, suspended life, where bodies placed inside transparent uterus-sarcophagi appear to be lit from within (just like Ecce Homo), becoming idealised human beings, spiritualised images, with the human body also becoming a model for creation.

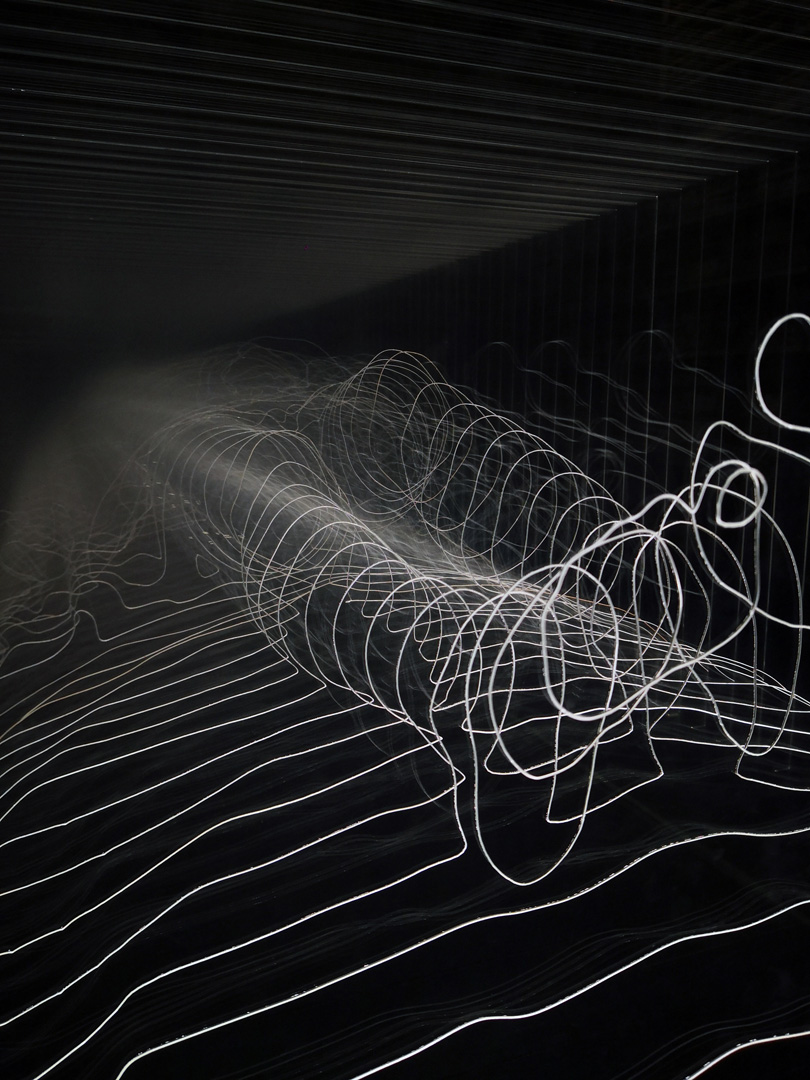

Ecce Homo takes this process of idealisation even further, the result being not a body, but a beam of light that takes on anthropomorphic form. At the same time, it is as if light embodies the idea in a form that can be perceived. This is not simply the replica of a reclining body, but its epiphany, where a figure of light that materialises acts as emanation, inserting itself into the visible world and becoming a unique representation of it. Instead of the figure, it becomes its radiance. This body, however, is not a single beam or ‘block’ of light. It is a body formed of fifty engraved plates. In a way, it works like a cinematographic image – a body in sequence, a sequence of bodies. If the moving image, in cinema, is made up of twenty-four fixed frames per second, then here the body is formed by the sum of its fragments impressed on the plate. In a similar way to cinema, where the frame is nothing more than an imprint of light, here each plate, backlit, bears an engraving with a partial outline of the body of Christ. In both cases a division is created, an invisible montage that implies the idea of having to go through a series of moments, each following the other. And if the photograms have moments of absolute unintelligibility (a halo, a sliver of light where there was previously a body), the plates bear imprinted, laser-engraved (light used to engrave light) traces that are absolutely minimal, aniconic. We are reminded of an essential aspect of vision: when we see something, we receive a limited piece of information – a feeling, a forerunner of what it could be. In a way, we see through hints, inventing everything else based on tradition and experience, because the real is always reconstructed. And Ecce Homo also suggests this: an elusive, multiform reality which comes into being and is configured a posteriori through accidents (incisions) reordered thanks to our memory. So the case, where the figure of light rests, becomes a stable surface of luminous inscription, a fluid maternal receptiveness where the reclining body attaches itself and is formed. The case represents a womb where the figure is always in the process of shaping itself.

Why is the image of a reclining body called Ecce Homo if the words refer to another moment in the Gospels, when Pilate shows Jesus, standing up, to the people, just after he has been beaten?

Because this body on the ground, which we have described as a radiant epiphany is, at the same time, the embodiment of all the forgotten, marginalised, humiliated and offended bodies in the world. An astral body is also the most material of bodies, reminding us of those who find themselves on the margins, shunned, without shelter (the case thus becomes a park bench, a pavement in the shade, a corner under an abandoned building), left on the margins of history. Ecce Homo is the body that sooner or later rises up, asking us to explain the reasons for its misery and our indifference.

In a final twist of thought, however, we see how the title, Ecce Homo, instead of being the presentation, the exhibition of a beaten and outraged body, becomes an exclamation when faced with a redeemed blow, meaning liberated: There you are, Man! And it is also the revelation of the other to ourselves and the other that can be found in each of us – torn, exposed, naked, alone, abandoned. He is a fellow man, our companion, our brother.

But this reclining figure is also beyond misery and turmoil, beyond abandonment and resistance, beyond defeat and victory. And the words of Revelation (21:4) come to mind: “And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain.”

Giovanni Festa

(this is an extract of the text that accompanies the installation at the Bank of Naples Foundation)

Cristian Rizzuti. Ecce Homo, Fondazione Banco di Napoli, Napoli, 09.04 – 15.05.2022