What does it mean to speak of Digital Humanities, Humanistic Informatics, or whatever name we assign to the encounter between the language of computer and the humanities? For quite some time literature has been accumulating on this topic. In Italy, Mondadori has just released in its Oscar collection Umanistica_Digitale [Digital_Humanities], a book published by the MIT in 2012, adapted and translated by Marco Bittanti.

This book tackles the issue of Digital Humanities presenting itself as a revolutionary approach to research, as the entrance to a new era for Academia, and also as a guide to a vision of contemporary world: «It is a global approach to knowledge—it is said in the preface—trans-historical and trans-mediatic.» Thus, five visionary academics, Anne Burdick, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner, and Jeffrey Schnapp, have climbed over the «fences» of Academia to broaden their view beyond disciplinary borders, in order to open a path for a new way of «making» culture. This volume, which follows a Manifesto published in 2009, is an experimental project, both theoretical and practical, and is also a «metalogue», that is, a dialogue taking the shape of what it is discussing. If this very discussion stems from the deep crisis affecting the humanities in the United States, such a topic is—should be—of particular interest in Italy.

Digital_Humanities offers some tools to exploit the digital world enormous potential in order to benefit the quality and the circulation of the humanistic culture, destined to be all but obsolete. For this to happen, one needs go beyond the mechanical transfer of culture into the digital dimension. Instead, it is rather necessary to adapt, interpret, elaborate, and make this culture alive through the several outputs at our disposition, so that it can establish an osmotic relation with the technological environment. We shall then be dealing with «Generative Humanities» that bring about «a mode of practice that depends on rapid cycles of prototyping and testing, a willingness to embrace productive failure, and the realization that any ‘solutions’ generated within the Digital Humanities will spawn new ‘problems’—and that this is all to the good.»

The fundamental assumption is to consider digital humanities not as a discipline but as a «convergence» of disciplines, as well as to upgrade technology from a «mere» role of supporter to that of partner in creating new modes of production of knowledge through new «creative rationals». New tasks and competences come to play. Among these: «curation», which includes the delicate selection of the data to be preserved; «computational analysis», often connected to the visualization of data; «editing», which becomes a «productive» and «generative» activity; «modeling», which is the «giving shape» to a given topic also by exploiting layout, typographic elements, and format to the content’s avail. In the title Digital_Humanities, for instance, the continuity between humanities and the digital is symbolized by the underscore («_») that constitutes a close link between the two words. Therefore design, which in this approach is understood also as project, acquires a key role. So does “gaming”, where experience contributes to the process of accumulation of knowledge.

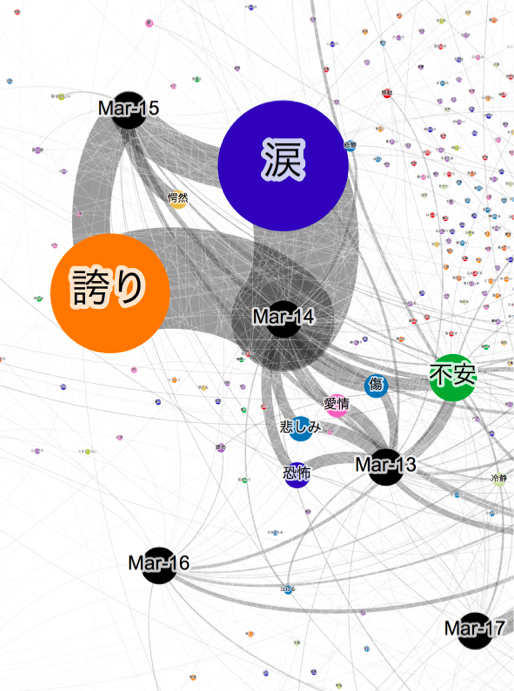

This all means to broadens one’s view and to start «perceiving» a reality where real, virtual, technology, communication, language, and anything that gets included in the new technological ecosystems interconnect. Design, for instance, with its function of data visualization, helps detect and map newly-born geographies, stemmed from the superimposition with invisible data architectures, as well as follow its continuous changing. It is through the lenses of this multiplicity of interconnections that each single discipline and technology must be understood. Print has not come to an end. Nevertheless we should relocate it within the larger network of models of communication that replace a culture that is exclusively dictated by print.

The humanities are historically rooted, the word speaks for itself, in man and in the human condition. Man is still at the center of everything. The point is then to understand what we mean for «center» and for the «whole». We live indeed in a space and time dimension that is polycentric and ubiquitous, where technology, from being «man’s extension» has eventually been inscribed in the genes. The empirical handbook here in review, addressed to researchers and academics, becomes a general guide, and help to tune our senses. They help us face the technological environment we live in, so that we can finally be in charge and be able to navigate it consciously, in order to attune with technology and turn it from torturer to accomplice.

Anne Burdick, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner, Jeffrey Schnapp, Digital Humanities, The MIT Press, 2012. This article is translated from Italian by Francesco Caruso and it appeared on Sole 24 ore with the title Ri_creazione digitale, on Sunday April, 27, 2014 on the occasion of the release of the Italian edition, Umanistica_Digitale, (traduz.italiana), Mondadori, Oscar saggi, Aprile 2014 (translated by Matteo Bittanti).

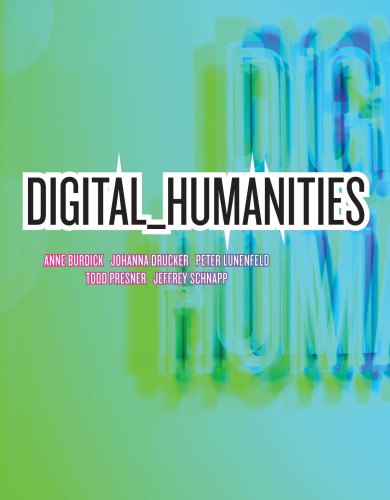

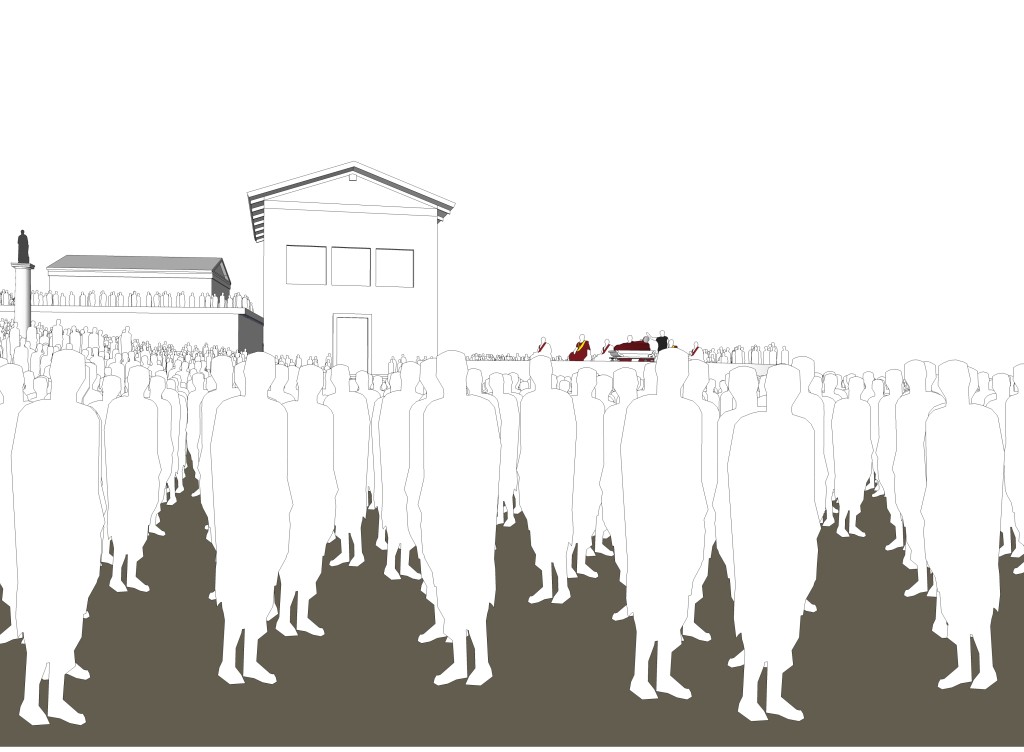

Images

(cover and 1) Image by RomeLab, a multi-disciplinary research group led by UCLA Classics and Digital Humanities faculty member Chris Johanson (2) Digital Humanities, cover of the American edition (The MIT, 2012) (3) a group led by Todd Presvner,Chair of the UCLA Digital Humanities Program, created this visualization of emotional content of 650,000 tweets over 30 days after the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster in Japan (March 11, 2011 – April 10, 2011) (4) Umanistica_Digitale, Mondadori, 2014, cover, Italian edition.