Bruno Munari (1907-1998), artist, designer, eclectic and visionary, but also a practical man, and an educator with a wealth of empirical experience, is, to this day, a constant source of inspiration and modernity. His methods of instruction are a point of reference. Among his many transversal and multidisciplinary interests, he dedicated much of his time and passion to the study of the intersection between art and technology. He discusses this in his book Fantasia, which is completely dedicated to the quest for fantasy, creativity and imagination in the field of visual arts. But what does fantasy have to do with technology? Evidently great deal when a visionary is capable of stripping it of its consumerist function. Munari expresses his particular fascination with cinema in Fantasia and tells the reader about how he and Marcello Piccardo filmed Tempo nel tempo in 1964 in a research lab/studio dedicated to the language of film located at Monte Olimpino (Como). This 3-minute, 16 mm film of an acrobat performing a somersault depicts the dilation of time. Using an instrument called the Temporal Microscope and shooting at 3000 frames per second to delay the gesture, the feat could easily be viewed over a period of three minutes. Seen like this, the image in motion becomes a part of sensory stimulations along with the overturning of the situation, the use of opposites, complements and the distortion of the matter and dimensions of the objects.

In his lifetime study of technological instruments, along with everything else that captured his attention, objects would lend themselves to his creative transformation of them into artistic and life experiences. Such works as his Fotogrammi/Photogrammes from the ‘30s – images impressed on the photographic support throughout the light and without the camera – and Macchine Inutili /Useless Machines (1933) – kinetic machines devoid of any consumerist intention – (to mention just a couple), freed works of their two-dimensional and static and transformed them into a spatial and temporal experiences. Munari’s creativity also persuaded major institutions to present their most experimental works very much before the time had ripened. In 1955, the MoMA in New York City displayed his Pitture proiettate / Projected Paintings and Pitture Polarizzate/Polarized Paintings – a series of abstract compositions enclosed in the transparent material of the slides whose projection on a variety of surfaces and from different distances resulted in constantly changing formats, shapes and topologies. And so, over the years Munari continued to experiment with anything and everything that piqued his imagination and curiosity.

How is it that Munari’s extraordinary ability to visualize has made it this far through time? Starting from an analysis of elementary shapes – from natural to artificial ones – he followed through to their eco-systemic organization into a single organic entity. Technology is often incorporated in his pedagogical experiments to filter nature in such a way as to create distortion and thereby prompt the imagination. Everyday items like leaves or onions filmed and filtered through the light of a projector reveal their structures as they suggest others. The light of the projector itself becomes magic when halted by the interposal of hands to create a game of shadow play. Every element is part of a learning experience connected to the relationships among the things Munari teaches us to search for in natural shapes before looking any further. «A leaf can be an object of exploration that reveals concealed relationships,» as elucidated in a chapter of Fantasia entitled Da Cosa Nasce Cosa / One Thing Leads to Another, which was soon to become an important publication regarding design. Fantasy, as intended by Munari, is an essential tool that we should call upon – now more than ever. Aside from its usefulness as a mental exercise, it also helps us to grasp the relationships linking technology to humankind in its symbiotic exchange. You can browse other experiments with technology and materials in the following years, as well as a wide range of hints of his vast production on MunArt, the website entirely dedicated to his work, including a selected bibliography and documents as well as a listing of all the current events that include his works.

Bruno Munari, Fantasia, Laterza, Rome-Bari, 1977

Images

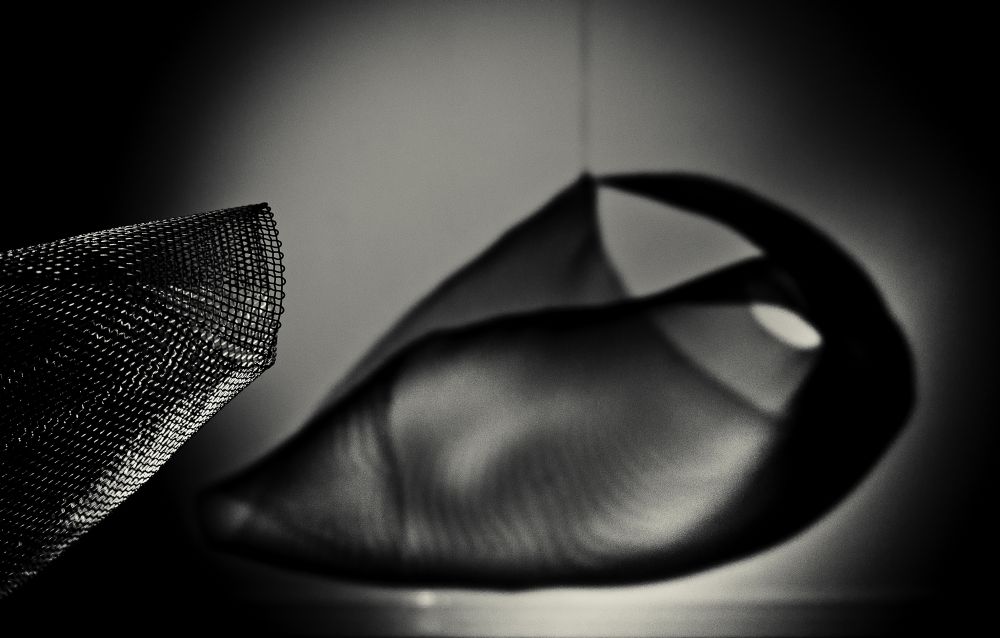

(1 cover) Bruno Munari Macchina inutile 1945-1995, Nicoletta Gradella Collection, photo ©Pierangelo Parimbelli; (2) Bruno Munari Concavo-convesso 1947, Installation at Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London, September – December 2012, photo ©Pierangelo Parimbelli; (3) Bruno Munari Macchina inutile “per Bill” 1951-1993, Zeni-Candioli Collection, photo ©Pierangelo Parimbelli