Among the artists in the exhibition Il video rende felici (Video Makes You Happy). Videoarte in Italia (Videoart in Italy), curated by Valentina Valentini, divided between the spaces of Palazzo delle Esposizioni and Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Rome, there is a rather dated work, with a retro look and underground charm. This work not only reveals the absolute freedom of video art – as if any proof were needed – but also reminds us how this type of art, which is as fluid as thought itself, can be created anywhere, in any conditions and using any medium. This work is Computer Comics by Giovanotti Mondani Meccanici (GMM).

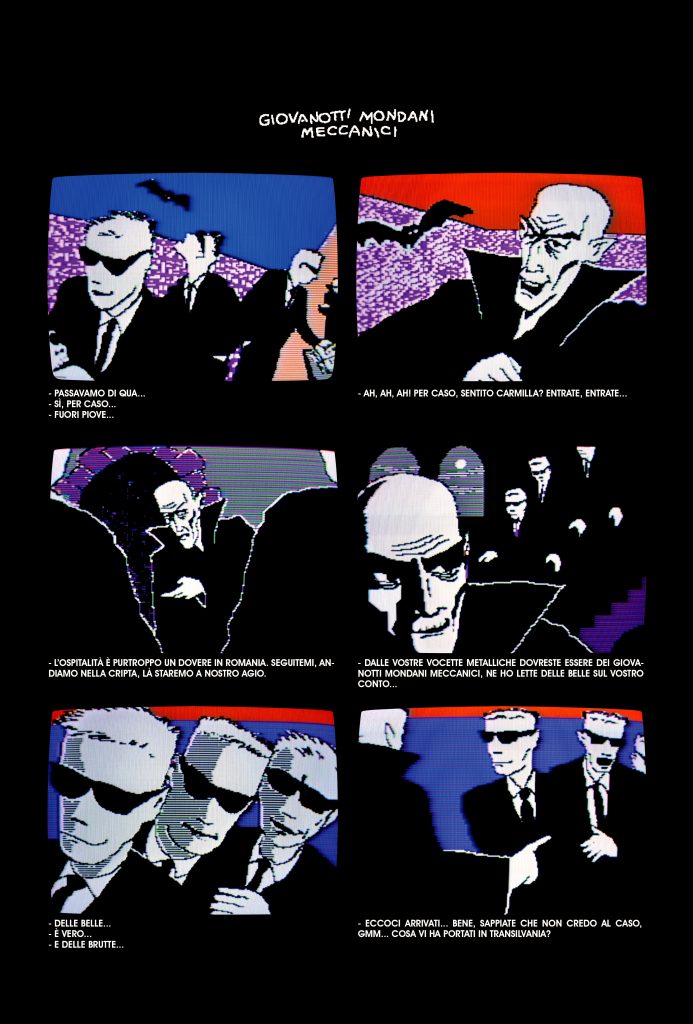

GMM are an artistic collective founded in Florence in 1984 by Antonio Glessi and Andrea Zingoni, who were subsequently joined by various other figures. They are the creators of the first ever comic strip produced in computer graphics, published in the legendary countercultural magazine Frigidaire. We are talking about the same magazine that gave birth to the equally legendary Zanardi, an imaginary character which sprung from the genius of Andrea Pazienza. These comics also immediately became video works: a video art that is atypical and cool, trash and ironic, narrative and computerised.

Computer Comics brings together the Florentine group’s first two video works: Giovanotti Mondani Meccanici (1984) and Giovanotti Mondani Meccanici contro Dracula (1984), projected in sequence in a room-environment composed of different elements. In front of the seats provided for watching the work in comfort, the projection “reverberates” on tulle before coming to a stop on the wall behind, as if to reveal the immaterial nature of the medium. Pixel-textures are simultaneously projected on the side walls while, beneath the invisible tulle wall, there is an Apple II computer (already present in the original version of the exhibition) where there is a running text written specially by Pier Vittorio Tondelli in 1984.

The narratives, always ironic, are visualised in 8-bit using large, anti-naturalistic pixels and alien, artificial, phosphorescent colours. The works depict the fictional adventures of the art collective – part mods, part neo-noir hyenas – certainly bad boys who often find themselves confronting horrific creatures, such as witches and vampires (who exceed them as ‘lords of the night’) and not only that.

The recurring elements of the 1980s underground, aestheticised through the cold but, thanks to GMM, expressive binary code are mixed with all those characteristics typical of computer art in the medium of video, representation of the natural evolution of the 1960s experiments of Whitney, Cuba and Csuri. These are developments that are still alien to the overcoming of the two-dimensional gap that goes towards making video art – purified by the filming of reality – a world apart, far more complex, immersed in kitsch, with everything to be discovered and still evolving. With the two-dimensionality dictated by the pixel grid, the computer exposes itself as such – an autonomous medium extraneous to reality and anchored in computer science, and hence mathematics which, as Gottfried Leibniz argued, is ‘the language of god’, the homogenous and all-embracing language par excellence. These operations, however, are not absolute (i.e. abstract) but, to all intents and purposes, figurative; hence they are based on mimesis, an element underlying the ontological fascination of the work, in some ways Pop. GMM, translated into bits, through their own programming action on the software – i.e. a self-portrait – reveal their antinaturalistic and cybernetic features, slaves to the protocol they themselves generated and yet apparently seen by the eyes of the machine itself, created in the processor and processed in the screen in a technologically “light” output, because they are formally linked to entertainment.

As we watch their schizophrenic comic adventures, we realise that GMM are addressing a subtext that speaks to us in the digital archaeology of almost half a century ago – a time gone by with all its mythologies. This is an electronic, at times cybernetic, niche world, in a still almost entirely analogue reality, with hindsight still very messy and unbalanced, which sees our protagonists as figures that are simultaneously analogue and digital in the space of both natural and technological reality, their own doppelgangers, simultaneously real and digitally ghost figures. But of course the laws of physics are not the same in different planes of reality: the immaterial doppelgangers meet Dracula without any short-circuits, which occur in the sequence of events, in which the three GMM are presented as the true antagonists of a Dracula who is unusually low-key. When compared to punk what is Draculean evil?

GMM’s final products (of which the first two works on display in this exhibition are the best examples of the collective’s disruptive primordial spirit) are purely postmodern in terms of media, narrative and linguistic hybridity. Focusing on shock (visual and conceptual) between counter-culture that becomes digital culture before it totally overtakes our everyday lives and punk counter-cultural overtones, GMM herald the essential characteristics of contemporary (high and low) entertainment. This aggressive and subversive collective, whose computer comics from 1984 to 1987 were reprinted in a single volume by NERO Edizioni last year, formed an interesting section to the broad narrative of Italian video art, one of the most fascinating to be honest. Even though it can be alienating to see their work alongside that of Studio Azzurro or Donato Piccolo, during the visit you can feel that they are necessary, as fundamental to the most modern hybrid digital art operations as they are to subcultural entertainment products, which about 10 years after the presentation of these works, with the birth of the World Wide Web, will lose their status of underlying popular culture, to become part of it, thanks to the massification of the Internet.

Il video rende felici. Video arte in Italia, curated by Valentina Valentini, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Galleria D’Arte Moderna, Rome, 12.04 – 04.09.2022

images: (all) Giovanotti Mondani Meccanici comics