Alberto Di Fabio – an artist with a quintessentially sensitive soul – always remains faithful to his way of working, methodical and like that of a monk, which he has pursued for years between Rome, New York and other places in the world. His artistic gaze is focused on cosmic, geological and biological matter in an attentive, almost surgical way, making space for himself through the layers of the invisible and bringing these to light. A shamanic process lasting more than thirty years, rooted in all those archetypal realities that man has been implementing for millennia in an attempt to communicate with the divine and mirror it. The first meeting for the interview took place in the artist’s studio April 16, 2021 during the filming of a video experiment. On that occasion, the gigantic canvases with organic and/or spatial landscapes were arranged as part of a kaleidoscopic set. We continued our conversation in the religious silence of his studio the following days.

Chiara Amici: You are currently working on a video project. Where does this need come from?

Alberto Di Fabio: I felt I needed to get out of the studio, to diversify the process and no longer focus on the exclusive relationship with colours, paper and canvases. Using different materials to talk about my stories. After many years one needs to explore and describe the world of the invisible, cinematography is another way of doing this; that’s why I asked young artists to reinterpret my works with their cameras. I’ve always been attracted by Max Ernst, Picabia, Man Ray, Salvador Dali… viewing masters from a dreamlike perspective, describing these visions in small films, short films that I would like to use in my next exhibitions alongside my iconic works – this was the natural evolution of a journey that had already began. In recent years, because of the same need to diversify my materials, I’ve created tapestries with the Pennese tapestry workshop in Abruzzo. A very interesting process. I’ve also produced mosaics and artist documentaries. I realised a dream to clean up and make a former dump in Ponza greener, where there is now a small wood. It’s important to seize the opportunity to regenerate and recharge one’s batteries, to get out of that obsessive state into which artists often fall, locked in their studios.

Many artists, quarantined all over the world, have learnt to expand their subjectivity once they found themselves locked down and are getting used to “going public” via social media, video conferencing or online exhibitions. What do you think should be the role of an artist in a context such as this? Is it a positive thing to be public?

It has been a very difficult, sad time. I cry for the new generations, for what years of dishonesty in public health and politics have brought us, making an already critical situation, such as that of the virus, much worse. We artists, who act as antennae, have suffered even more. In a way, the artist’s condition is, of itself, difficult and lonely, but when museums and galleries are also closed, the situation gets much worse. In this situation, everyone has used the media of their choice – using the virtual to recreate a positive emotion is welcome – and then, in this period, digital works have been sold for thousands of dollars and euros. Personally, I’m not very social: this year I have experienced interviews, calls and even some online group exhibitions, but I found myself declining all the requests I later received because I felt these experiences were too “ethereal”. I prefer to present my work live, to feel and experience the moment and the people. During this period I’ve been working, creating and dreaming a lot… I can see the path I should follow, a single truth made up of magnetic energy and infinite levels of frequencies – the right one should be seized. Through social media everything takes on a different perspective. I see how, for new generations, success and inner happiness is seen as something quick and immediate, and so everyone wants lots of likes and tries to satisfy an audience of strangers. To create a work of art, however, you need a slow process of gestation, reflections taking months, years. History will filter everything… even these difficult moments.

Do you think that the new generation of artists, perhaps because of this tendency to condescend to social media, are witnessing the loss of a personal philosophy?

I don’t feel it’s my place to judge. Like so many have done in the past, I too perhaps make the mistake of considering my generation better than the next one. Art changes, as does music, and the whole world is in flux. We’re all very self-centred and it’s easy to say in a simplistic way that the young people of today don’t want to work as much as people did in the past, or that they use techniques which are too simple and immediate. After all, when I was in my twenties, a seventy-year-old artist was saying the same thing about me. I’ve learnt over the years that my personal opinions have not always been correct, so it’s good to look at others, at the younger generation. Judging is easy, but creating a good intellectual philosophy that is recognised over the years is completely different. Wanting to become famous is basically just a mental masturbation of one’s ego: it’s the work that becomes important, not us. Thinking too much about success distances one from the real, authentic goal. I always say that you have to be alone in the studio working and praying while, at the same time, always keeping an eye on the art system. It’s a complex world, one day making you fall in love and the next making you sick.

Which work or series of works do you feel most attached to?

In my life I’ve researched various subjects, philosophies and ideas, but I can say that I’m very attached to some of my works from the 1990s. At that time I was concentrating on smelting processes, mountain landscapes and mountain ranges moving over metaphysical deserts. In these works I wanted to reflect on landscapes and thinking matter, in movement. They were works dedicated to Giotto, Carrá, De Chirico and Sironi. Very different from the abstract paintings of recent years where I’ve looked up at the sky, the universe and the stars, reflecting on how our synapses connect and unite with the magnetism of the cosmos. Looking back at those mountains I go back again into the earth’s crust. I feel warmth and happiness. They are iconic works of mine which I’m very attached to.

Spirituality is at the heart of your art. How did your particular relationship with religion begin during your life?

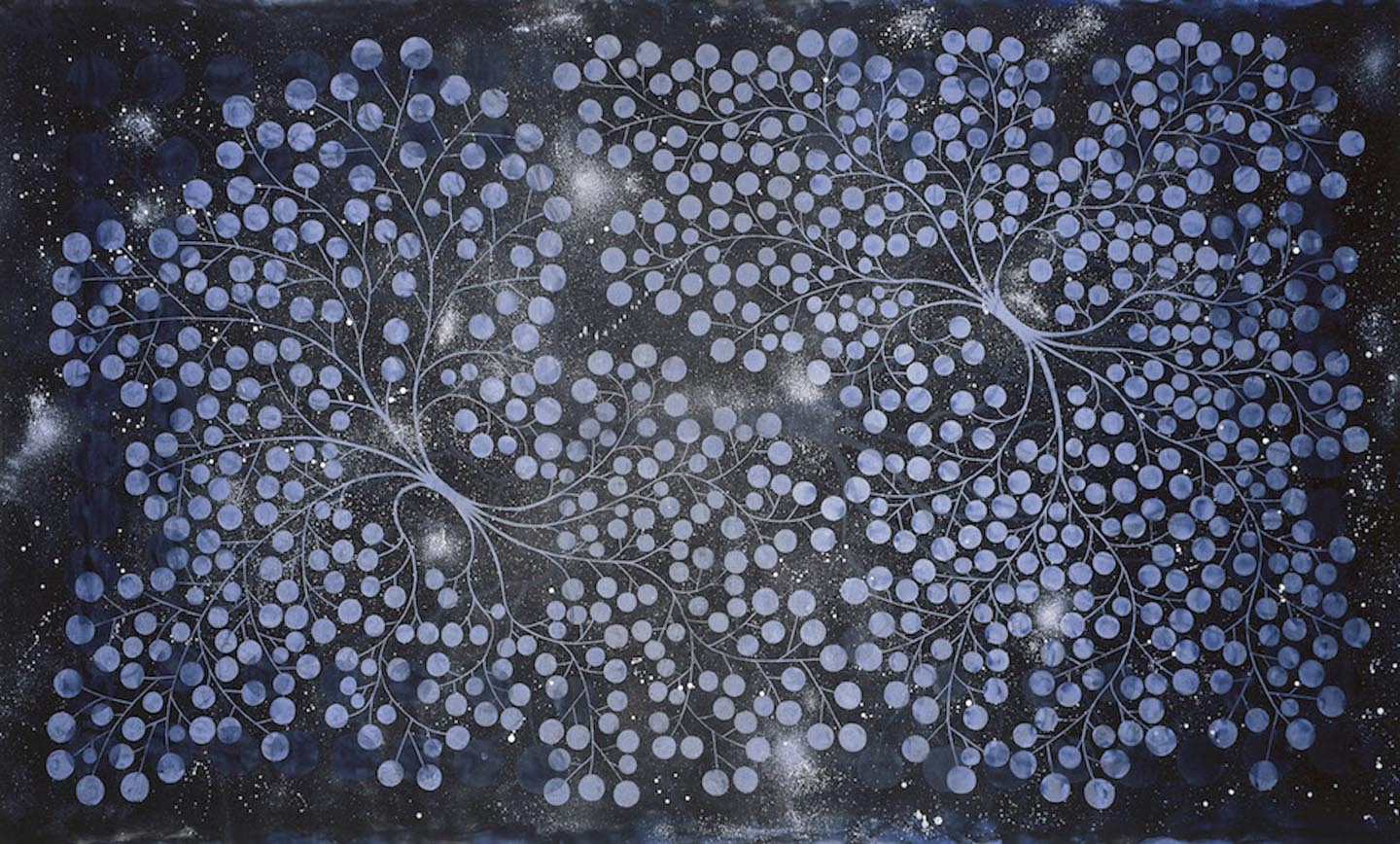

I think religion is a human attempt to understand infinite and impossible processes and our minds are drawn to it like an amulet. The very work we do – that of the artist in my case – is a religion. We humans have been aware of some enigmas for a very long time and we use various tools to answer these questions and reach a personal condition of ecstasy, contact with the world of the divine. Every time I describe my works as dedicated to science and religion, my creative acts are forms of prayer. Many works describe the human brain with the synapses and neurons that create our magnetic body. It would seem that we human beings perceive very little of what really exists and our gaze is always turned to the sky, to the indescribable horizon: from building a ladder or a wheel we have now moved on to the study of antimatter, the Higgs boson, the God particle. As Leopardi’s poem says: beyond that hedge, towards the invisible, I cannot see, but the wind that moves these cypresses makes me feel that perhaps I can perceive that “something”. Religion, science, mathematics and art… It’s a whole. A God who beats alongside us. I use every element available to talk with this being and describe it.

In your family, there was a common interest in an “other” dimension: from your artist father, Pasquale Di Fabio, to your sister Tiziana, a poet…

I was very lucky, but also a bit unlucky to have a family such as mine. My father was an artist and we only talked about paintings and sculptures together. He often said that we could remove the crucifix from the bedroom and replace it with a painting by Mondrian or Malevich. He loved minimalism, pure abstraction and throughout his career he continued to search for absolute light, creating infinite lines in absolute spaces, describing his divine cosmos. These were particular concepts that, as a child, I only partly understood and yet they were my “daily bread”. My mother taught me maths and science. We had bookshelves full of shells, minerals and science books. I had two sisters who were older than me: Simonetta studied medicine and immunology while Tiziana had a literary background and ran a dance theatre company. I learnt to study with my sister’s medical books and my mother’s natural science books. Dad often asked us: “Which do you prefer? Colour television or can I make another steel sculpture?” We didn’t know what to say! We wanted colour television and, at the same time, we wanted to see our father happy to produce another work. There are artists who started painting very late in life, such as Matisse, but being lucky enough to be born into a family like this facilitated many of my existential journeys, helped me to define my own path. Sometimes I wonder if maybe I could have done another job. But, after all, we’re all in this stormy sea, always full of doubts. The important thing is to follow our path of light, which leads us to peace and inner pleasure. This is the road I had to take, full stop.

Do you follow a daily routine or any rituals in your life to put you in touch with your spiritual reality?

In my studio I like to listen to classical music or jazz, and to loosen up I use dance or instinctive movements similar to Tai Chi. My amulets are the tools of the trade: my brushes, my favourite paint, which I keep near me even if I don’t use it… We artists are craftsmen, but we are also like shamans; we have our eternal symbols and hope that they help us to dream.

Your paintings show spatial landscapes, views of synapses, but also psychedelic colours and shapes. What do you think about the spiritual quest achieved through psychoactive substances?

We humans are small beings, crushed by an enormous force of gravity, subject to our bodily needs such as breathing and eating… To elevate ourselves we need that part of the sphere which belongs to the oneiric, the spiritual, and we achieve this through meditation, prayer and ritual movements, or we need wine, magic herbs and sex. Unfortunately, we are tied to a constant biological state that keeps us bound to the earth. In my works I try to describe parallel worlds, invisible matter. Like religion, mathematics and philosophy, the use of certain substances leads us to be able to see things that are beyond our normal perception. Substances, whether synthetic or those used in ancient rituals, are interesting experiments to which man has dedicated himself since the beginning of time. However, I believe that endorphins, breathing with all the energy we already possess, are all that are needed to take flight.

If you could describe your work in words, which would you choose?

It’s not easy. Some verses by Ibn Arabi, the great Arab philosopher and poet, come to mind: “I am the reality of the world, the centre of the circumference, I am the parts and the whole. I am the will established between Heaven and Earth,I have created perception in you only in order to be the object of my perception.” These words make me think of how many times we ask ourselves who we are, why art exists, what it’s for… Perception, after all, is already something wonderful, nothing else is needed, and by perceiving others we can perceive ourselves. And yet, we can never really know ourselves or others. We’re a fusion of different types of human knowledge: mathematics, space, dreams and poetry.

We’re matter destined to deteriorate. Ours is a transitory state. Are we only here because of a divine will? Just to be objects of His perception?

In one of your interviews I read that you wanted to write a great book…

I’ve written a novel and many catalogues describing my works, with contributions from many writers in different languages. I find the literary aspect a very important part of my work. I’d like to write a book of genesis (laughs), a universal book, for the future. I don’t know if I would ever be able to do something like that, so when I walk in the mountains, fall asleep under the stars or in the shade of a tree and I feel a sense of great wonder, I dream and hope, like Moses, to receive the gift of a sacred text.

Which place has inspired you the most during your travels?

For me every place is geographically undefinable and nameless. I have a strong inner drive to travel and learn about cultures, to be nourished by images of the world. I’ve been to Nepal, North America and Mexico several times and can’t forget the magnificent views I was able to see. My best memories are in the Alps, the Pyrenees, the Colorado mountains and the Himalayas. The mountains, the rock formations, are wonderful sights for me.

You are currently one of the most international Italian artists. Is there something you dream of achieving in your artistic career?

I don’t see an end point. I don’t feel I’ve “arrived” yet and I’m never fully satisfied with what I do, just like everyone else. I feel small and would like to grow up. I often tell myself that one lifetime is not enough… when I listen to Bach, read Shakespeare or see a film by Antonioni I feel like a grain of sand in an infinite desert. My willpower keeps me going in this dark tunnel where there never seems to be any light to signal the end. I think the important thing is to keep believing, desiring and always striving towards something great, an unreachable dream for an infinite verb.

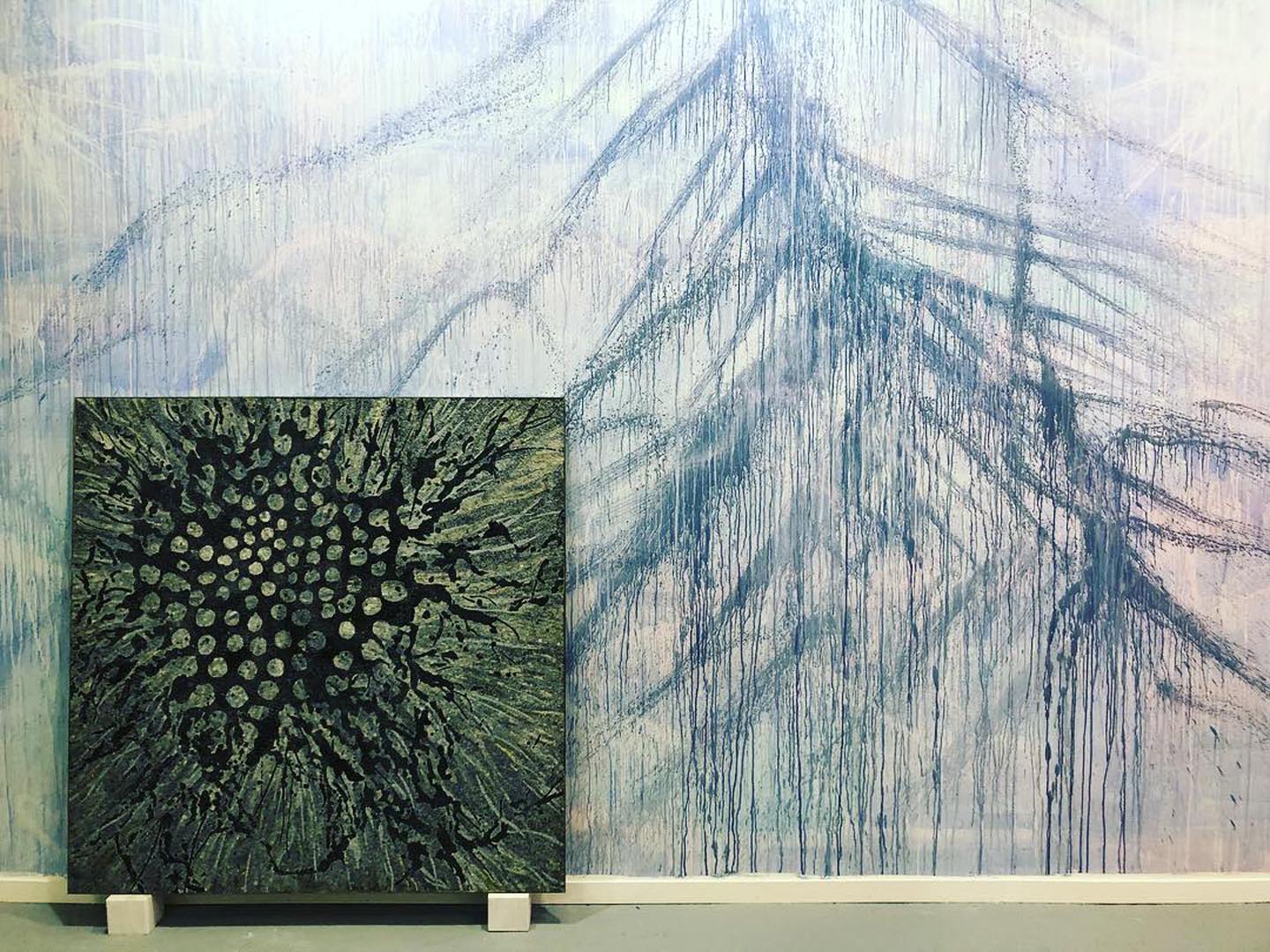

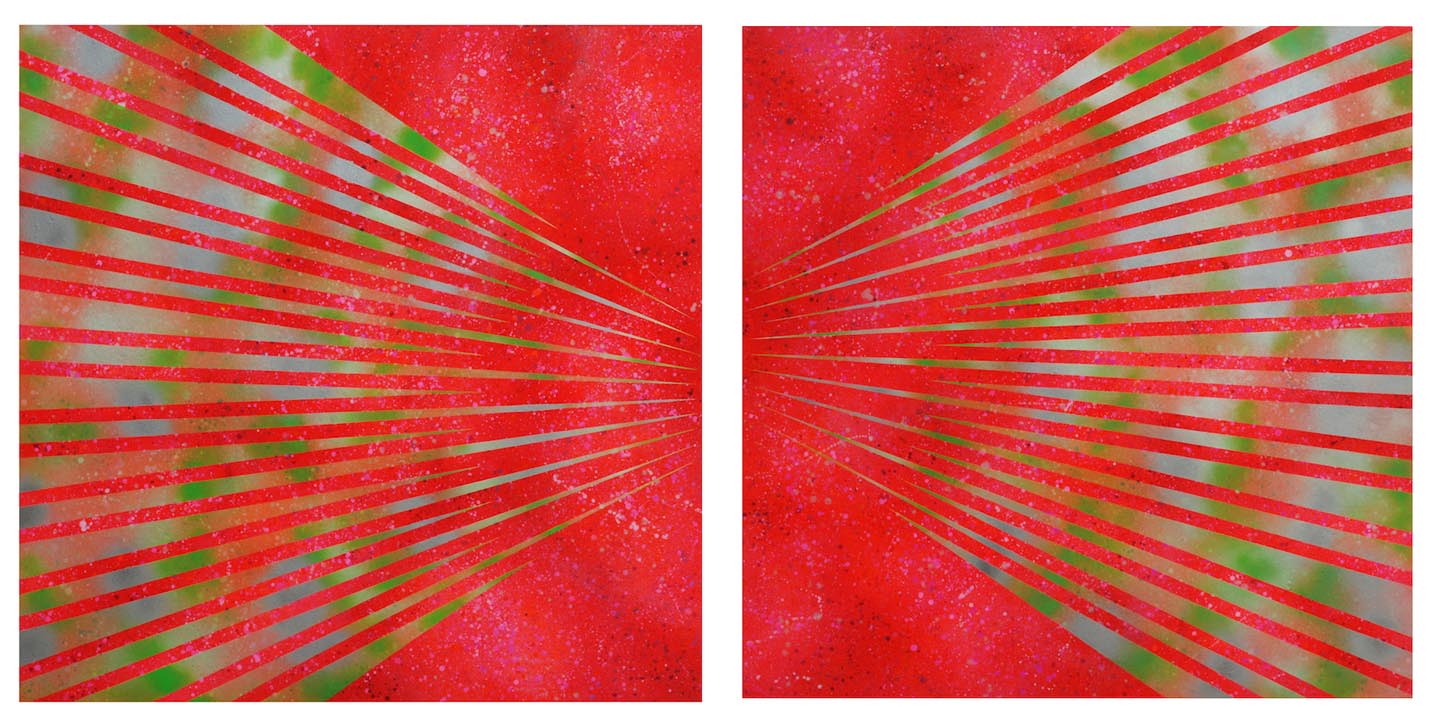

images: (cover 1) Alberto Di Fabio, «Paesaggi della mente», Museo Macro, Rome 2015, photo: skino ricci quinta studio (2) Alberto Di Fabio, «Illuminazione, Paesaggi di una materia invisibile», 2020, wall painting, Luca Tommasi Gallery, Milan (3) Alberto Di Fabio,«Copia di Realtà Paralle», 2012, installation at Galleria Nazionale D’Arte Moderna, Rome (4) Alberto Di Fabio, «Materia pensante», mosaic and wall painting, Artefiera Bologna 2018 (5) Alberto Di Fabio, «Realta’ Parallele», 2011, acrylic and lacquers on canvas, diptych, each 120 x120 cm (6) Alberto Di Fabio, «Sinapsi + Cosmo», 2006, acrylic on canvas, 200 x335 cm. courtesy Gagosian Gallery (7) Alberto Di Fabio, «Un mare di atomi», 2007, Galleria Pack, Milan