At the Royal Spanish Academy in Rome, from 29 May to 14 June 2020, the exhibition “Riattivando Videografie (Reactivating Videographies)” took place, curated by Estibaliz Sádaba Murguía. The event, which focused on video art, included an Italian section curated by Anita Calà, founder of Villam, and titled Speculare il Caos (Mirroring Chaos) including artists: Francesca Arri, Matteo Attruia and Lamberto Teotino who have all been active in the contemporary art scene for many years.

The Rome event, taking its cue from the complicated historical moment we are living in, gave rise to an important international project that brought together 64 video works which, over the course of a few months, merged into a dedicated online portal, becoming an important international reference point for video art.

Valeria Coratella: The project “Riattivando Videografie” developed from an idea by Estibaliz Sádaba Murguía to present three former Spanish scholarship holders from the Royal Spanish Academy wanted to pay homage to Rome by including an Italian section with as many artists. You were invited to curated this section that you titled “Speculare il Caos”.

Valeria Coratella: The project “Riattivando Videografie” developed from an idea by Estibaliz Sádaba Murguía to present three former Spanish scholarship holders from the Royal Spanish Academy wanted to pay homage to Rome by including an Italian section with as many artists. You were invited to curated this section that you titled “Speculare il Caos”.

The two sections, which were designed separately, generated a single project that soon afterwards became global, creating an important archive which is now available online. I would say that you have been far-sighted in proposing an exhibition on video art, since it is the most real and authentically employed means of expression for the viewer at a time when museums are closed. Do you think that, commercially speaking, this new period resulting from the pandemic could make collecting move towards video art in a more conscious way?

Anita Calà: I had been aware of and admired Estibaliz’s work for a long time so when I was offered a collaboration with her in an institution like the Royal Spanish Academy, I was delighted.

Working with an individual like Estibaliz in a location that, in my opinion, is one of the most beautiful places in the world, can only encourage you to do your best.

I had little time to select the artists and works to present, but if I went back and had three times as much time, I would make exactly the same choices.

There was research and attention to detail. I wanted to present a project that would please the whole organisation.

Unfortunately the event in March was eclipsed by a reality we all know about but, unlike many other situations, it wasn’t stopped. On the contrary, the event became even more powerful. In a short space of time and in the middle of a pandemic crisis it evolved into a wide exchange and collaboration between 65 artists and two collectives from 17 countries, connecting 18 cultural centres with the Royal Spanish Academy, and involving 23 curators. The strength of this combination of energies is to be found, above all, in the desire to have a common future vision.

Video art is a direct and easy-to-use virtual medium, so it’s “easier” to make a project visible and visitable even without the physical presence of the viewers. At the same time, it’s one of the most difficult forms of art for a wider audience to understand and it’s also difficult from a commercial point of view.

But I believe that for an artist it’s necessary to think about his or her work without concentrating on the aspect of collection, especially now that we live in a divided era.

The art economy has to be reviewed as in many other diverse working environments. There must be a greater commitment on the part of all of us who work in this sector to find alternative ways to just collecting and stronger foundations to ensure economic stability for the world of culture.

It will be a long search. Covid has only revealed a situation that has been brewing for a long time.

Another difficult aspect of video art is keeping viewers focused and keeping them glued to the screen until the end without getting bored. The platform that hosts the project is “cunningly” structured as a social portal; scrolling down the page automatically activates the videos. You can listen to the audio and get more details about the work simply by clicking on the video. In your opinion, what is the right way to approach a viewer who is not used to video art?

Listen Valeria… I’ll get straight to the point: art is not for everyone, and it’s my opinion – but it’s debatable – that there should be no way or method for bringing people in, when they do not even have the curiosity to understand or appreciate the work.

We know very well that the lack of ability to understand a work of art is also a consequence of a lack that begins with the school/education system where there are no teachers able to make modern and, especially contemporary art, accessible. During the exhibition I visited at the Royal Spanish Academy I noticed that in the rooms, next to each video, there were sheets of paper on the wall with excerpts of poetry and an introduction to the work; expanding on your ideas, I would like to add that maybe the work doesn’t even need to be explained… what do you think? Was this your idea or a format the Academy wanted to implement?

There is a frightening chasm in cultural education in schools. I remember that when I was in junior high school (centuries ago) art education was treated both by both students and teachers like a gym lesson in the garden, a sort of second break. Obviously, afterwards one grows up and follows one’s own inclinations, but certainly such a superficial method towards art in a “malleable” age doesn’t help even those who are not gifted to be stimulated.

Even today, talking to people of all ages, when they discover that I work in contemporary art, they insist on asking me “Yes, but what do you do?”. At first I used to get angry… now I have given up. I realise that art is not for everyone (as I said before) and this is as it should be.

This brings me back to your question as to whether a work should be explained or not.

I think it’s right to include the explanation of the poetics in an exhibition, especially when it’s an exhibition in an institution open to the public. I personally rarely look at such explanations, but it’s also right to introduce an artist to those who do not know him and are curious about his research. It also rarely happens that someone from the club of “Yes, but what do you do?” goes to see a contemporary art exhibition and asks himself whether he should or should not to read the explanations.

Collaboration with an institution plays a fundamental role in terms of prestige for a project. The event can be facilitated by the presence of sponsors who pay for expenses; communication is more targeted and makes an impact; and there are multiple resources available. Unfortunately, however, there are compromises to be made which are absent in privately organised events. During your curatorial experience, what constraints have you had to face vis-à-vis institutions?

The experience with the Royal Academia of Spain has been like a beacon in the dark… I felt at ease straight away. Estibaliz left me carte blanche regarding the artistic and technical choices I made. The institution in this case has been open and available – practically a paradise.

It’s not always the case, as you said. Despite being helped with some aspects, collaborating with large institutions can sometimes make people feel bound by bureaucratic constraints.

Personally, in the course of my past experiences, I have found it more difficult when I couldn’t initiate a dialogue with the people working in bureaucratic offices. Sometimes we are faced with people coming from other sectors, not related to the cultural sector, and this creates a short circuit in communication. One must be armed with true dedication and patience.

Among the artists of Speculare il Caos we find a video performance by Francesca Arri, a work on LCD by Matteo Attruia and a video installation by Lamberto Teotino. In general, what do you think of those videos that are initially conceived only as an archive document of a live performance and that are then “used” as a video work that enters the sales circuit? Do you this it’s a commercial stunt to earn money on a job that would otherwise have no place in collecting because it’s ephemeral? Or do you think it’s an aesthetic/artistic necessity?

A work can have different types of visual support. It’s the concept that shouldn’t be fragile. Any form in which a work is presented is welcome, both for technical and commercial reasons.

Analysing the exhibition I noticed that despite the different supports and poetics there was a formal coherence in the design of the exhibition. Despite the short time you had to select the artists and the works, it seems that you already had the exhibition in mind. Could you tell me something about the three Italian artists you presented? Which of them, from a spatial point of view, has created more difficulties for you in terms of their position?

Arri and Teotino are two artists with whom I have been working for a long time. I admire their work for being so “bad” and direct. In different ways they both punch me in the stomach. Arri does it by screaming at you, seeking physical confrontation with her research. Teotino, on the other hands, divides you with a very thin blade without breathing.

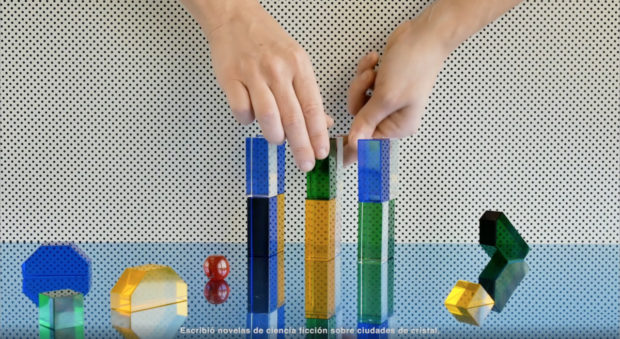

This is the first time I’ve worked with Attruia. I’ve been following his work for a long time and this seemed to be the right opportunity to test us. The world where this artist leads us has just the right destabilizing charge that I like so much… its irony attracts us but it’s actually a red herring that takes you inside a mechanism consisting of word play underlining the fragilities everyone shares.

The setting was quite simple. I had an austere exhibition in mind from an aesthetic point of view. Lamberto Teotino’s work was perhaps the most complex, as it was not only a video but a complete structure. The artist meticulously searched for the right support to perfectly match the image he had in mind. Lamberto is a master in this. His art is made up of perfect details and he doesn’t stop until his idea materialises, otherwise he divides you with a very thin blade without breathing.

«Riattivando Videografie», curated by Anita Calà, Estibaliz Sádaba Murguía

Real Accademia di Spagna, Rome ( 29.05 – 14.06.2020) is now online on a dedicated platform.

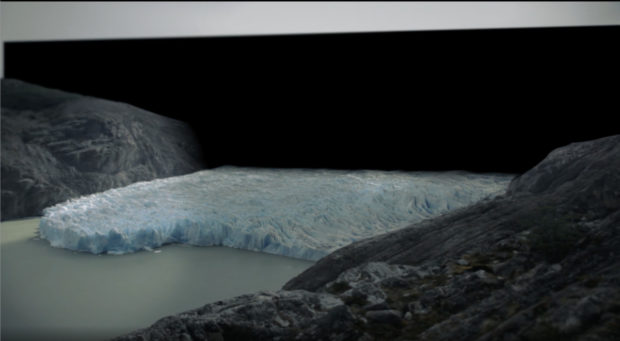

images:(cover 1) Florencia Levy, «Paisaje para una persona», 2015, Centro Cultural de España en Buenos Aires (2) Francesca Arri, «Selfportrait», videoperformance 2012 (3) Erik Tlaseca, «La noche (no) es muda», 2018-2020, Centro Cultural de España en México (4) Donna Conlon, «From the Ashes (De las cenizas)», 2019, Centro Cultural de España en Panamá (5) Susana Sánchez Carballo, «Gritos Mudos», 2017 – Centro Culturimmaginial de España en San José (6) Erik Tlaseca, «La noche (no) es muda», 2018-2020, Centro Cultural de España en México (7) Nicolás Rupcich, «EDF», 2013, Centro Cultural de España en Santiago de Chile (8) Andrea Canepa, «The tale of the mass, the grid and the mesh», 2020, Real Academia de España en Roma (9) Matteo Attruia, «All I need is all I need», 2020 (10) Lamberto Teotino, «Non-physical entities», 2020