David Rokeby’s (1960, Tillsonburg) is an interactive sound and video installation artist based in Toronto, Canada. His early work Very Nervous System (1982-1991) was a pioneering work of interactive art, translating physical gestures into real-time interactive sound environments. It was presented at the Venice Biennale in 1986, and was awarded a Prix Ars Electronica Award of Distinction for Interactive Art in 1991. Several of his works have addressed issues of digital surveillance, including Taken (2002), and Sorting Daemon (2003). Other works engage in a critical examination of the differences between human and artificial intelligence. The Giver of Names (1991-) and N-cha(n)t (2001) are artificial subjective entities, provoked by objects or spoken words in their immediate environment to formulate sentences and speak them aloud. David Rokeby has exhibited and lectured extensively in the Americas, Europe and Asia. His awards include a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts (2002), a Prix Ars Electronica Golden Nica for Interactive Art (2002), and a British Academy of Film and Television Arts BAFTA award in Interactive art (2000). Interviewed by Eva Kekou, David Rokeby discusses the role of sound in his interactive installations, his perspective on the current state of surveillance and the influence of Marshall McLuhan.

Eva Kekou: Can you please give us some information about your work Very Nervous System (1982-1991) which is acknowledged as a pioneering work of interactive art, translating physical gestures into real-time interactive sound environments? How does sound relate to place and space in your work?

David Rokeby: Sound is immersive in a way that image can only dream about. Sound touches the skin. Subwoofers rearrange our viscera. We can take no distance from sound. I did not start working with sound in Very Nervous System for this reason. I just loved playing with sound. But sound had two distinct advantages as a medium for creating immersive interactive environments in the 80’s. One was the inherent immersive nature of sound. Second was that computers had just enough power to convincingly play and manipulate sound, but were really barely able to generate any sort of satisfying image in real-time.

Sound has both more and less place than image. Sound is a fairly transferable reality, in that a sound can take its place in many different environments or contexts without much effort. Sound collage is inherently different than image collage in that sounds mix together fluidly on a perceptual level even when the mixture is incongruous. In terms of Very Nervous System, this meant that the experience of interacting with the sounds had a seamless bleed into the sound experience outside of the installation. If you walked along a city street after interacting with Very Nervous System for 15 minutes, you found yourself adopting a relationship to the sounds of the street that assumed a level of interactivity, a lingering of the Very Nervous System Experience that was strangely natural-feeling. Visual experiences can also leave this sort of lingering resonance, but they tend to be more disruptive in my experience.

The experience of space is also different. Using sound in Very Nervous System allowed me to embed the space with invisible possibilities. These sound potentials would be drawn out by a certain quality of movement sometimes further limited to a certain part of the space. But you found unleashed these potentials by moving through space, and because sound is heard not just in the ears but by the whole body, you felt the presence of that sound as a feature of that particular chunk of space you were, say, moving your hand through. McLuhan liked to say that «space is sudden to the blind man», and this is how Very Nervous System felt: surprising and sudden, but at the same time very tangible and spatially consistent.

Interactivity (direct) is a feature of primary importance in media art. How dramatically is the change on the art scene and the audience perspective? How has your work evolved since receiving a number of awards?

I don’t think that interactivity dramatically changed the reality of the arts. But I do think that it was surprising to people because they had become accustomed to a passive role, especially in relation to recent media like television. Any decent artwork draws the audience into a sort of dialogue in which the audience is not nearly as passive as it at first may appear. The irony for me is that my initial intent in creating an interactive artwork was not to highlight how active the artwork could be, but rather to remind us of how responsible we are as the audience for bringing the artwork to completion, using our own ideas and memories and dreams and fears.

I do think that interactivity makes it easier to present active metaphors and relationships, and to turn an idea into an experience in a way that was not very easy to do previously. It allows you to give a tangible presence to an abstract idea… allowing you to live with the idea not as a maneuverable set of symbols in your head, but as something to question and confront with your body in physical space. The truth is, however, that there are very few things that have been done in interactive systems that were not previously done perhaps in a different way in other art forms, by artists who were interested in creating in this way. Interactive technologies provided an ideal medium through which to continue these explorations. And they took the ideas related to interactivity which had been lurking in various practises and brought them together into a self-conscious practise in which these issues of audience engagement were the focus in a way that they had not really been before. Unfortunately, the interactive art «movement» has been a little too tied in underlying technologies and a kind of techno-positivism. I think of my interests in interactivity as being predominantly social, political and philosophical, with the technology being a marvellous enabler for those explorations.

Surveillance seems to play a crucial role in your work. In examining Including Watch (1995), Taken ( 2002) and Sorting Daemon (2003) how do you consider current signal surveillance as an issue related to global politics, art and activism?

I think that signal surveillance is one of the most important issues confronting global politics, art and activism. As far back as my installation Guardian Angel in 2001, I was thinking that on-line surveillance was much more of a concern than video surveillance itself. The recent revelations from Edward Snowmen show us how vulnerable we are becoming as we increasingly rely on technologies that leave an instant, accessible, electronic trace. Florian Rotzer noted back in the late 1980’s that total interaction requires total surveillance. We are seeing this play out. Our highly interactive and interconnected on-line lives trade us goodies and convenience for extensive, and continuous personal data. My biggest concern is that we will wander into a state of total dependence in an atmosphere of relative political calm, but should there be any political upheaval in our particular community / city / state / country, the framework for extreme social control will be already in place. Just recently, protestors in the Ukraine were texted by their phone provider that they had been identified as being at an anti-government demonstration based on their cell-tower and GPS based location. As we have seen during the Arab Spring, these technologies can be tools for political activism, but this is only true until the powers-that-be clue in and make use of the power in their own way.

The McLuhan project has toured in major cities including Toronto, London, France and Berlin (Canadian Embassy). The importance of McLuhan is obvious. How does this relate to your sound project in particular to a digital sound installation which has successfully toured among different cities. How influential is his personality?

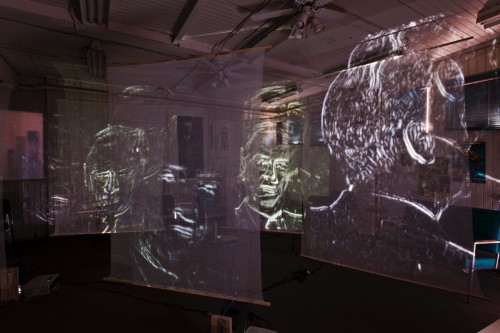

In terms of Through the Vanishing Point, my intervention was video and Lewis Kaye’s was audio. But in fact, the challenge that I faced with the challenge for presenting a video representation of McLuhan was that he hated being photographed or filmed or videotaped and was very uncomfortable with visual representation in general. I decided that I wanted to create a visual portrait that McLuhan would approve of. To do this, I looked at his writings about sound and the acoustic experience of space, and tried to apply these ideas of the images and the ways of presenting them. This felt very natural to me because I started out as a sound artist and feel that I still make visual pieces using the aesthetics and positions of sound art.

One of McLuhan’s issues with visual representation was that it presented an excessively continuous experience, in that a visual experience of space puts everything in the visual field into a clear and undisrupted continuum of spatial position and distance. The completeness of this visual experience of space removes one from one’s other senses and one’s body, and dampens the imagination. He was very fond of pre-perspective imagery in which the continuity of space is disrupted with outlines and floating figures and unrealistic changes of scale. He preferred art where the artist had painted what he or she knew rather than what he or she saw.

In contrast to visual space, he felt that acoustic space was very resonant, interrupted, and disrupted… open to possibilities. I tried in my part of Through the Vanishing Point, to present the imagery in a disruptive way, with 7 semi-transparent screens arrayed through the space which overlapped in the spectator’s visual field creating a discontinuous space. I also used image processing of archival film and video to present a layered field of moving outlines of his head / torso / body which created what looked a bit like a vibrating network of neurons stretching through space.

In terms of McLuhan’s influence on my early sound work, there was little direct influence at first. I think in Toronto, McLuhan is in the air… his ideas are in the drinking water. At any rate, I must have absorbed some of it by osmosis. When I first read «Understanding Media», in the late 80’s, I was stunned by how much what of I was doing was in line with his thinking. It was a really exciting read!

I got connected starting in 1985 with the McLuhan program at the University of Toronto because the co-director at the time, Derrick de Kerckhove had seen an early version of Very Nervous System at the Hart House Gallery at the University of Toronto and was very excited about it. He talked about and presented the work many times over the years and shared some of McLuhan’s ideas and some fantastic anecdotes about McLuhan. However, McLuhan thought that I was still pretty unschooled until I was invited to create Through the Vanishing Point with Lewis Kaye, which was to take place in the old coach house at the University of Toronto where McLuhan worked and taught.

I spent a lot of time watching films and videos of McLuhan, and reading more of his work, and developed a much deeper appreciation for him and a courageous, risk-taking, ground-breaking multi-disciplinary approach. I feel close to him as a fellow artist… I think he was, among other things, a brilliant performance artist disguised as a university professor.

I imagine the sound has a significant role in immateriality and that it is important to analyze the function of the connection between materiality and immateriality. More specifically in digital and media art projects, where materiality has a power over the work in the first place.

I don’t really understand the full intent of the question, so I will try to answer as best I can. Sound is immaterially material. It can be physical and visceral while still being massless and ephemeral. This makes it a special kind of «bridging» medium. On the other hand, sound is so easily edited and synthesized and manipulated that it is often added to media artworks without any real consideration for why it is there. Most of my recent pieces are silent. I promised myself 13 years ago to add sound to my pieces only where it was essential. This is because I care deeply about sound and love it as a medium and am tired of sound as a habitual addition or mere soundtrack. I have started to add sound again after this self-imposed moratorium. Some pieces I have created recently would have benefitted from sound, and I am in the process of working on this.

Can you you tell us anything about your current projects? What are your future projects and plans?

I am working on an interactive sound and video work called Hand-held, an invisible three dimensional sculpture, which is only revealed as you touch it. It reveals itself as a field of images that appear on your hands. It is a piece in which I am playing along the edge of tactility and virtuality. In a sense it is a bit like an expansion of Very Nervous System into the visual realm. The work was initiated when I was an artist-invité at Le Fresnoy in France. It originally had no sound and is one of the pieces which I am now carefully augmenting with sound. I also am interested in extending this piece into the realm of language… to create a spatial sculpture of language which you read with your hands. The text branches in space, but also contains simultaneous layers of meaning… The dimension of depth holds a space of semantic ambiguity… and these simultaneous, parallel and often contradictory texts flicker and fade into each other across your hands as you read / explore.

Images

(cover) David Rokeby, VNS in 2003 at the Ace Art gallery (Winnipeg, Manitoba), photo by William Eakin, Risa Horowitz and Liz Garlicki, courtesy of David Rokeby and Ace Art Inc. (1) David, Rokeby, Through the Vanishing Point, 2010, photo by Toni Hafkenscheid. (2) David, Rokeby, Taken, 2002, installation view at the National Art Museum of China (2008), photo by David Rokeby. (3) David, Rokeby, Through the Vanishing Point, 2010, photo by Toni Hafkenscheid. (4) David, Rokeby, the artist in Very Nervous Systems in Potsdam, 1994, photo by Lambert Blum (5) David, Rokeby, Through the Vanishing Point, 2010, photo by Toni Hafkenscheid. (6) David, Rokeby, Taken, 2002, installation view at the National Art Museum of China (2008).