The conversation with Delphine Valli, an artist who has always been committed to researching the tensions created between artistic intervention and space used as a plastic element, took place as part of the residency project The Impossible Present, a project reconnecting Valli’s creative research with the traditional Islamic matrix from which it originates. From the project, winner of the 10th Italian Council edition, a series of designs for Walldrawings and a series of events will be created to bring together international realities working in the artistic (FAI-AR, Mucem, Marseille), philosophical and scientific (Opera Mundi, Marseille) fields, culminating in a publication that will present Valli’s entire work for AlbumArte.

Elena Giulia Rossi: Can you tell us about your residency project? How did it come about and how far have has it taken you up to now?

Elena Giulia Rossi: Can you tell us about your residency project? How did it come about and how far have has it taken you up to now?

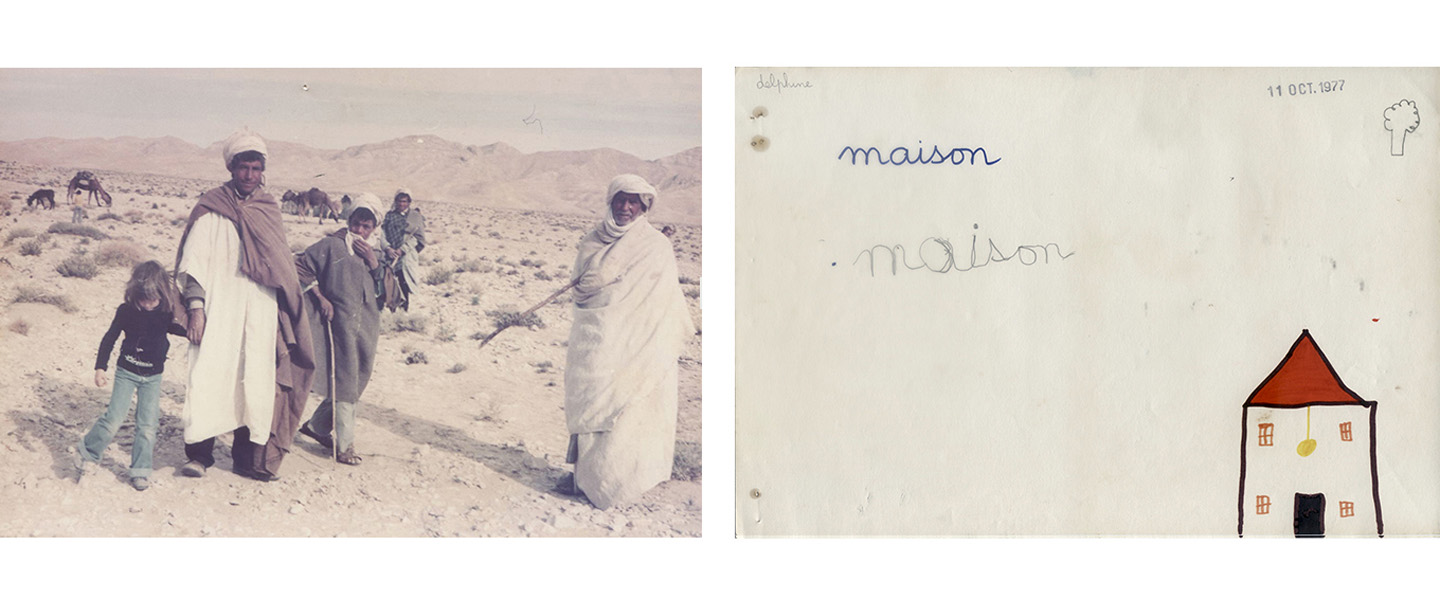

Delphine Valli: The project, which confronts the impossibilities of time and addresses personal questions, arose not only from the needs mentioned above, but also from the need to reconnect with the Islamic culture I experienced until I was 16, in Algiers. The dialogue with Melania Rossi at the time of the project’s drafting was fundamental with the relationship between Islamic art and my work becoming evident. The aim of Islamic art is to encourage an understanding of the underlying reality and, because the divine figure – invisible by nature – cannot be represented, Islamic art has internalised the spiritual.

This pressing need to reconnect with the culture in which I grew up was not just an existential necessity, but intrinsically related to my work that was, after all, taking me back to it.

In particular, the need to reconnect led me to think of a convergence of knowledge, through dialogue with my cultural partners, AlbumArte in Rome and the Mucem, Opera Mundi, FAI-AR and Les Ecrans du large in Marseille, where I lived before coming to Rome. We will perhaps have the opportunity to talk about this later, but let’s say that my centre of attention has shifted southwards, bringing together three cities in the Mediterranean basin that have links to me, shifting my gaze towards the Maghreb which, basically, has a different world view from the West.

I needed to understand more about what I had been doing for years in a way, it seemed to me, that was fundamentally intuitive, almost as if I was a part of a cryptic intention, with no distraction possible. The need to stop and think and process what has been achieved. This need was also motivated, after the shock produced by COVID, by the global crisis of which climate change is only one of the effects. We are already facing a direct existential threat, according to the UN, an organisation which is not usually particularly alarmist. A large number of living species are already dead. We are talking about the sixth mass extinction. What is killing us is our fear of imagining an alternative to the current unsustainable situation. As Aurélien Barrau, astrophysicist and philosopher, points out, stopping to think is revolutionary today.

The question is also not external at all to my personal research. I started from the invisible data, which shapes my work as much as material aspects do. The times we live in confront us with the fact that its great challenges are linked to the invisible, as art critic Nicolas Bourriaud reminds us (pollutants or the virus that has been affecting us for 2 years now are both invisible) and which have been confirmed by recent discoveries in quantum physics. It can also be said that the human psyche, like our societies, is founded on the ability to remove, thus making invisible what is disturbing.

Cultural confrontation, including the diversity of perspectives, is as crucial today as ever and provides the focus of your research, which starts with studies of Islamic culture. Perspective – here understood as viewpoint and gaze – exactly represents a possible starting point for a discussion of the relationship between the two cultures with images. Your images, those that are recomposed through the gaze, appear to be situated on the borders between several worlds: geometric patterns and lines tracing invisible spaces follow the space and the world, going beyond all that is ‘finite’, thus superseding the threshold of the possible.

As you point out, East and West stand on two distinct shores, and the adoption of perspective in the West, which places the human being and their gaze at the centre, transforming the world into an image, has radically conditioned – now on a global scale – not only the view of the world, as an anthropocentric symbolic image but also, as Hans Belting points out in Florence and Baghdad. Renaissance Art and Arab Science, ‘The globalisation of perspective, supported today by Western-model television and press, has an astonishingly long history in the West’s colonisation of other parts of the world and in its missionary activities on behalf of Christianity. In this process perspective was virtually forced on people of other cultures, who had to give up their own established modes of seeing.”

You rightly say, speaking of my geometric patterns and lines tracing invisible spaces follow the space and the world, going beyond all that is ‘finite’, thus superseding the threshold of the possible, that I could not find a better synthesis of my objectives, motivated by a sense of asphyxiation felt in the world as it presents itself to me.

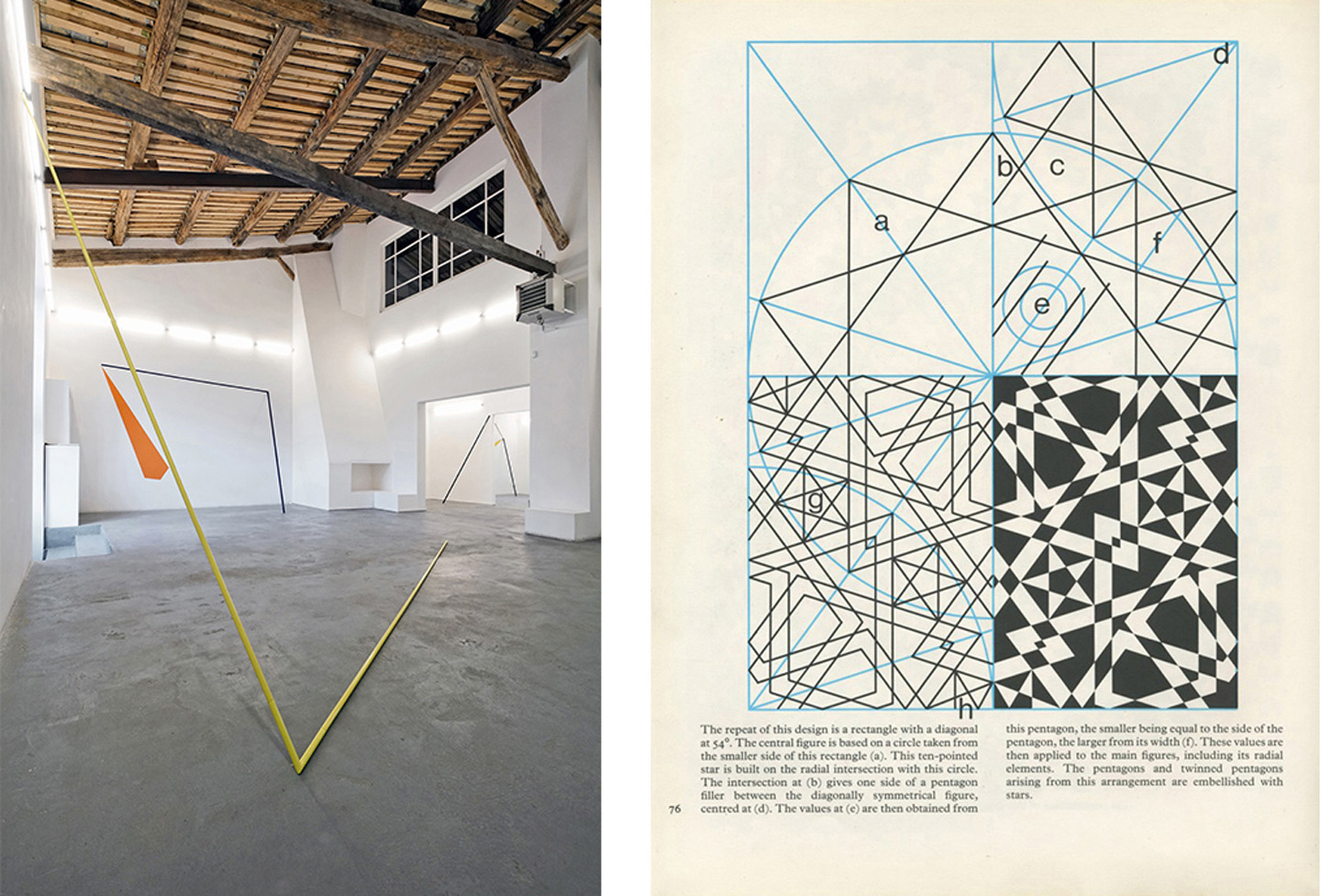

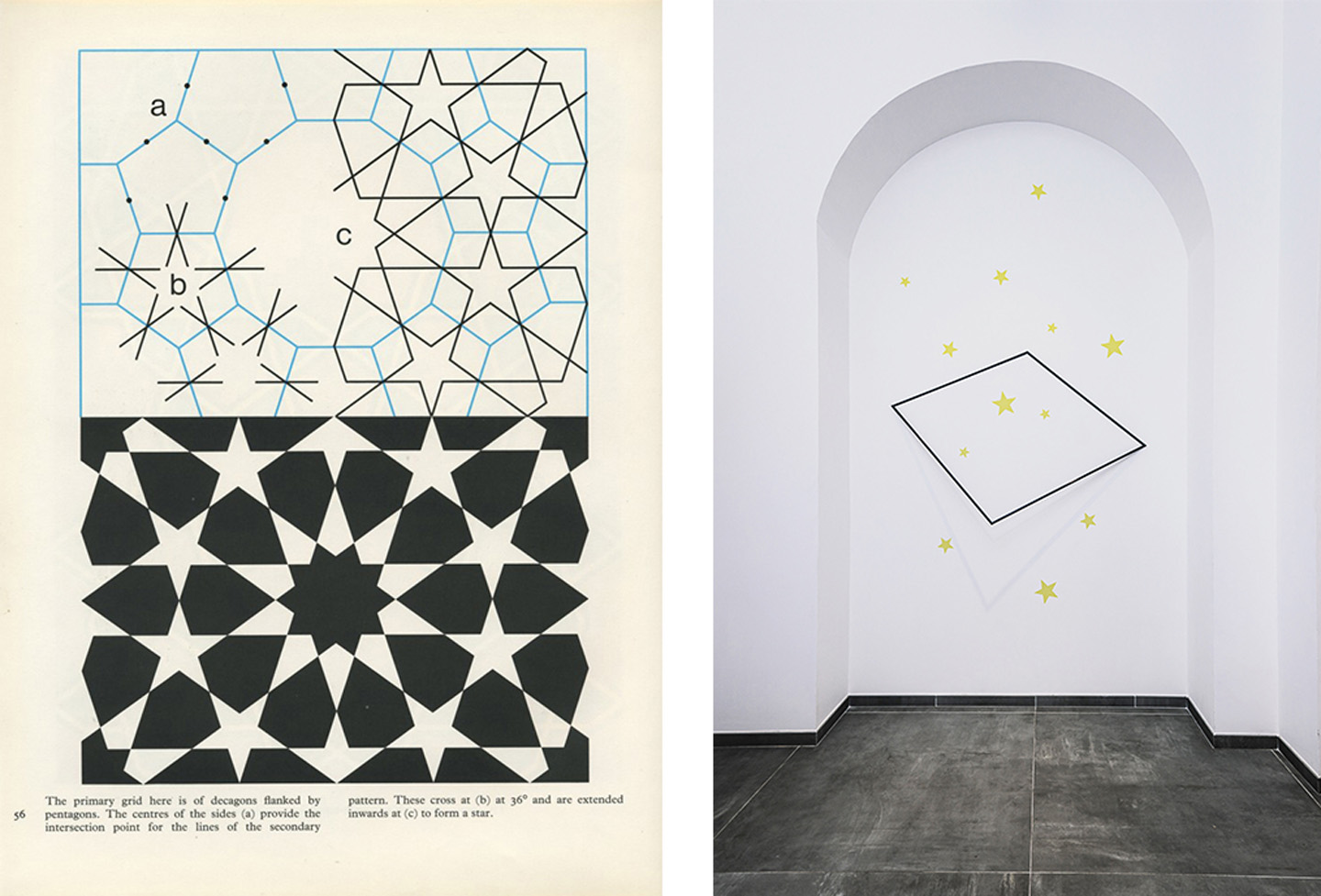

We continue our journey with Belting and his canons of the gaze. From the outset, the fundamental difference separating the Western from the Eastern image is made clear, the latter of which is based on the theory of light. I’m now thinking back to your works, such as the ones made for the AlbumArte space on the occasion of your solo exhibition ‘Climax’, curated by Claudio Libero Pisano. Your works are geometric patterns designed ‘for’ and ‘with’ space, as if tracing something invisible that connects space and the world goes beyond, as we have already said, goes beyond the ‘finite’. What role do light and space play in all this?

Space, like light, responds to physical laws. Islamic art, derived from scientific study, the observation of rays of light, particularly in Alhazen’s camera obscura, and also mathematics, is not concerned with images. If anything, it is about visual forms. To understand what this means. we can take the example of a form seen through water, which is not the same as one seen through air. I observe spaces as physical bodies that, as such, respond to physical laws. Light propagates, pervades space and, above all, can be seen by us, but this is not in relation to our gaze – light travels along its own trajectories.

Belting notes that “The girih style in Abbasid culture, with its linear structures covering entire surfaces (strapwork) purifies the eye, removing impressions of the bodily world. (…) Beams of light serve as an organizing principle in interiors in the same way that patterns of lines function on the walls. Such disembodied arrangements seem to make the walls and limits of space disappear, an effect brought about by the dominance of light and pattern over all material substance.” I cannot help noticing a profound affinity with the way I understand my own artistic practice, which aims to undermine the limits of the ‘finite’.

How has your outlook changed with this awareness of your own work and how do you expect it to spill over into the journey you will take into your native culture, including a comparison of cultures and perspectives that will inevitably ensue?

Reading Hans Belting’s book is like a journey of awareness in reverse. It takes me back to the world of my childhood, to the point of feeling overcome by this gaze without limits and I retrace, alongside Alhazen’s 11th-century discoveries, the unique features of a culture that I ate raw, to borrow an expression from Picasso when he wondered if we were meant to eat the raw wonder. The anthropocentric perspective that is now demonstrating its limits infiltrates all contexts. It was illuminating when I realised how representation based on perspective may have shaped our outlook by globally imposing – through colonisation and more recently through the media – a cultural system and worldview on mankind. After this period of study and reflection, the idea of reconnecting with places steeped in Islamic culture means that I can unite with them again, both physically and spiritually, with all the memories that live within me. I imagine a readjustment as if since I left Algiers I had been living far from a terrestrial centre, where my heart continued to beat, while in my artistic work the culture which had shaped my approach to the world resurfaced.

In the construction of your project, you needed to ‘change course’. The impossibility of going to Algiers, your country of origin, and the rerouting to Morocco, and its departure from Islamic culture, represented an objective obstacle in your path. What did this mean for you and how did your research project develop as a result?

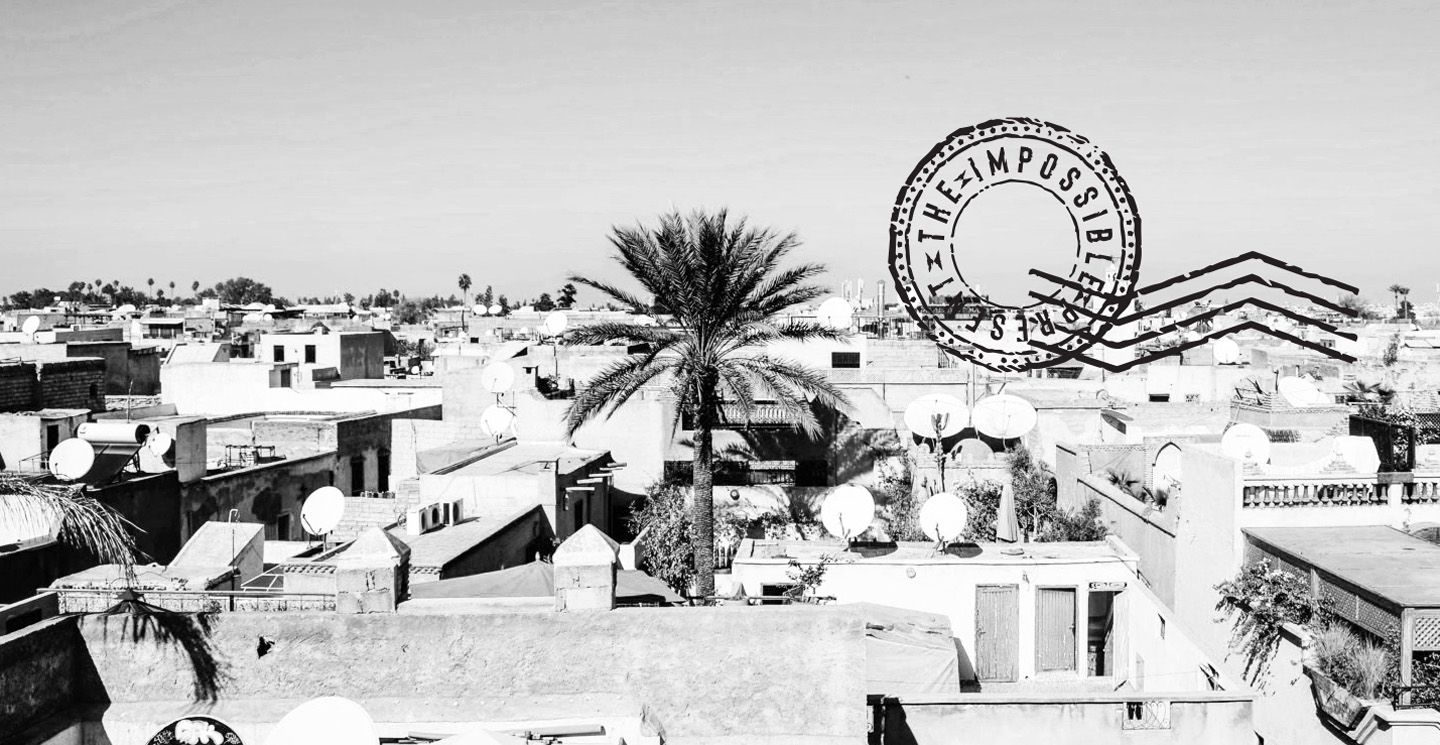

Yes, in fact, my return to Algiers was revealed to be impossible. For political and administrative reasons. Usually, a return is conceptually impossible, utopian: there is no going back in time. This is a theme I have been discussing since 2019 with Giulia Fabbiano, an anthropologist and co-curator with Camille Faucourt of a forthcoming exhibition at Mucem, to be held in 2023, on this very subject – Rêvenir. Expérience du retour en Méditerranée. I also discussed this in Real Utopias at Manifesta, in Marseille, with Melania Rossi and Bianca Cerrina Feroni. I came across an impossibility shared by many people who cannot go where they want. An experience always needs to be shared because you only really understand it first hand. This experience taught me a form of detachment, how to overcome tension. With Cristina Cobianchi we “hijacked” the residence at LE 18 Derb el Ferrane, in the Medina of Marrakech. As one of my most cherished wishes evaporated, a new possibility emerged, free from the difficulties of months tied up in Algiers. This openness seemed consonant with the project, which seeks a viable way forward in a contrasting present. I am in contact with La MaisonDAR, which could host me in Algiers, and something may come out of our dialogue to be included in the book I intend to produce with Parallelo42 Contemporary Art, a cultural sponsor, representing the culmination of my project.

Delphine Valli, The Impossible Present, Le 18 Derb el Ferrane, Marrakech, Marocco

Curatorial support: Melania Rossi | Cultural Partners. Marseille: Mucem, Department of Research, Opera Mundi, FAI-AR at Cité des arts de la rue, Les Ecrans du Large at La Friche Belle de Mai; Rome: AlbumArte | Cultural sponsor: Parallelo42 Contemporary Art

Project supported by the Italian Council (10th edition, 2021), program to promote Italian contemporary art in the world by the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity of the Italian Ministry of Culture

images: (cover 1) Algeri, view of La MaisonDAR, ph. Abed Abidat, Logo Parallelo42 Contemporary Art (2) Portrait of the artist, drawing by the artist, Algeri, 1977 (3) Delphine Valli, «Ciò che si oppone, converge», iron, Ex Elettrofonica, Rome, 2009, ph. Ramy Leon Lorenco, Scheme by David Wade (4) Schema di David Wade, Delphine Valli, «Tensioni in superficie», AlbumArte, Rome, 2019, ph. Luis Do Rosario (5) Delphine Valli, «Tensioni in superficie», AlbumArte, Rome, 2019 – ph. Luis Do Rosario, Scheme by David Wade (6) Marrakech ph Giulia Maio, Logo Parallelo42 Contemporary Art (7 )Scheme by David Wade, Delphine Valli, «Real Return From Utopia», painted iron and tempera walldrawing, Real Utopias, MANIFESTA13, Marsiglia, 2020 ph. Guido Mencari