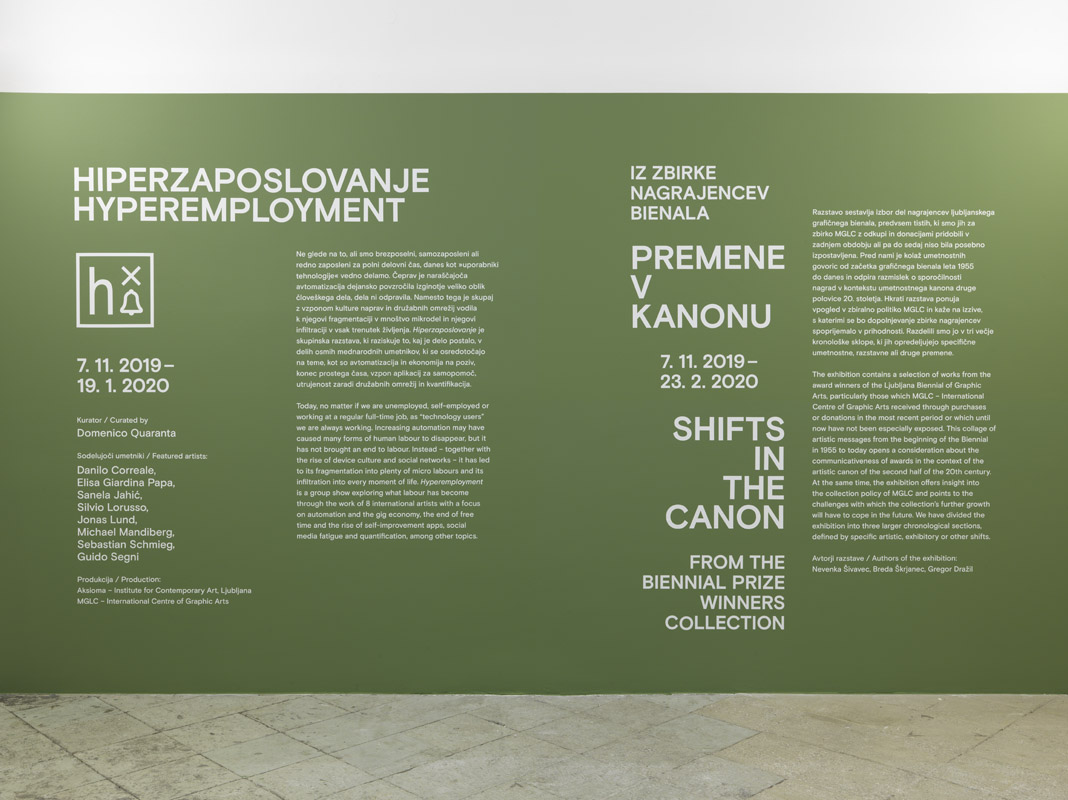

Domenico Quaranta talks about Hyperemployment, the exhibition that he curated at MGLC – International Centre of Graphic Arts in Ljubliana, dedicated to “the exhausting work of the technology”. The project is produced by Aksioma and it is part of a larger programme with the same name, focused on post-work, online labour and automation, and co-curated by Domenico Quaranta & Janez Janša.

Elena Giulia Rossi: The ‘crisis of labour’, its precariousness and fragmentation, driven – among other things – by the automation of production processes and our growing ingestion of Artificial Intelligence, is the subject of the artistic research brought together in a project which will extend for an entire year, with an exhibition, a symposium and a series of other events, from performance art to book presentations. Can you tell us how the project came about?

Domenico Quaranta: The impact of technological advancement on labor is a subject I touched upon briefly in Cyphoria, my curatorial contribution to the 2016 Rome Quadriennale, and something I felt the need to explore further, since in various ways it lies at the heart of the work of many artists I follow. I started discussing it with Aksioma over a year ago, and the outcome was the idea for a collective exhibition to be presented at MGLC, the International Centre of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana. But the more we discussed it, the more we realised two things: on the one hand, the format of a group show was not broad enough for the development of a topic that was so complex and wide-ranging; on the other, the matter had many points of consonance with Aksioma’s general programme for 2020, in part because of its collaboration with Rijeka 2020 – European Capital of Culture, which hinge around the keyword “Dopolavoro”. At a certain point it seemed natural to bring together the MGLC exhibition, its various spin-offs (like the Automate All the Things! symposium, which will take place in January) and some specific projects in a single programme extending from November 2019 to November 2020, co-curated by me and Janez Janša, Aksioma’s Artistic Director.

Hyper is the prefix of Hyperemployment (as mentioned in the introduction to the project, it’s a term borrowed from Ian Bogost); it also refers to everything in contemporary (Western) culture that’s reflected in its links with technology: we’re hyper-connected, hyper-busy, hyper-active…

Ian Bogost coined the term “hyperemployment” in 2013 to describe the “exhausting work of the technology user”. In particular, Bogost focuses on how the organisation of work has become work in itself: work which, in this always-on age of smartphones, creeps into our living time, eliminating any separation between working time and free time. Essentially, hyperemployment is the condition which turns us – regardless of whether we’re employed, unemployed or under-employed – into “employees” of the devices and apps we use for work and entertainment. It’s a controversial concept, and when it was first proposed it came under harsh criticism from feminists, as Bogost appears to acknowledge as “employment” a series of activities – individual management, personal care – and a time – spent in household tasks – which were absolutely not considered as such when they were perceived as strictly female pursuits, handled by secretaries and housewives. Personally, I still find the concept useful and interesting for its generality and open-endedness, which means it can encompass aspects of our current circumstances that have emerged (or have been noticed and examined in greater depth) after 2013: from online work mediated by crowdworking platforms to the monetisation of our activities on social media and of the data we casually hand over in exchange for given services, which even turns things like our sleep and our leisure time into work; or the fragmentation of work into such minuscule units we don’t recognise it, nor understand that it should be translated into a wage (whenever I complete a captcha, tag an image, underline an e-book, I’m contributing to a system that generates profit for a company which gives me nothing in return).

How do the artworks in the exhibition relate to hyperemployment? It’s really interesting to see how some of the artists venture into space and time – increasingly obsolete – that’s associated with the absence of work, such as leisure and sleep…

One of the greatest contradictions in late capitalism is that the dynamics of post-Fordism and growing automation in manufacturing are effectively eliminating work as an activity limited to a separate space-time dimension (the factory, the office, the working day); but instead of leading us towards a post work society, this is creating a situation in which working time and space is coinciding with our time and space for living. The most transparent expression of this contradiction is the situation I find myself in right now, answering your questions from my laptop at the kitchen table. When you work from a computer at home, work, leisure and entertainment interrupt each other constantly. A notification might force you to take a short break or temporarily set aside a task to deal with a more urgent one. A cigarette break becomes an opportunity to see what’s happening on Facebook, post on Instagram or check your emails. Work reaches you in the pauses of your day: at lunchtime, between one episode of your favourite series and the next one, between the shower and the hairdryer.

Silvio Lorusso’s work in the exhibition, which draws attention to the phrase with which one of the most popular self-optimisation apps – StayFocusd – interrupts “recreational” computer time, shines a light on this specific problem. The very existence of this kind of apps demonstrates that all barriers between working time and free time have broken down, and can only be rebuilt artificially (and delegated to machines, since we can’t do it ourselves). Shouldn’t you be working? Leisure and recreation are fragmented into countless tiny micro-moments and succumb to a series of dynamics which may vary but concur to cancel out their effects or contaminate their nature. Is posting on Instagram leisure or work? It can be fun and give us a distraction from a less enjoyable task, but it’s work in the sense of the self-entrepreneurial labour of building and nurturing our public image (not by chance, the results are quantifiable); and it’s work because it boosts the finances of a company which offers us a free service as long as we become its product.

As we see in The Labour of Sleep, the work by Elisa Giardina Papa which explores the world of sleep-monitoring and optimisation apps, this process does not even spare the quintessential non-working time, paradoxically “democratising” what was once the privilege of the artist and the creative worker. Artist at Work (1978), the famous series of photographs in which the Croatian artist Mladen Stilinović stigmatised the 70s capitalist obsession with production, also reclaimed leisure and sleep as the realm of thought and imagination – “productive” in and of themselves. But today sleep is indeed work, because while helping us to sleep, these apps absorb our biometric data and convert them into capital.

In Demand Full Laziness, Guido Segni films himself in a pose very similar to Stilinović’s, his aim being to generate visual material to educate artificial intelligence, to which he will delegate his production in the course of a five-year programme of deliberate abstention from work. The project ironically references one of the slogans of Accelerationism (“demand full automation”), but in reality what it appears to show us is the impossibility of leisure, its evolution towards a utopian projection of oneself. From another angle, this project raises the question of the possibility of the complete automation of artistic work and subjectivity -a topic raised, in very different ways, by two of the other exhibits, by Jonas Lund andSlovenian artist Sanela Jahić. Meanwhile, the subject of leisure time is explored in a manner both paradoxical and, paradoxically, functional, by the Slovenian artist Sašo Sedlaček in his ongoing project Oblomo, which will be presented in the course of the Hyperemployment programme at various stages of its development. Combining surveillance technology, artificial intelligence and cryptocurrency, the project monitors inactivity and stasis and converts it into economic value: only complete immobility allows the process of mining the cryptocurrency to be activated and progressed.

Returning to Artist at Work, American artist Michael Mandiberg shows us an image of the artist at work that’s more apt for today’s world with Quantified Self Portrait (One Year Performance), a project created in the course of a year between 2016 and 2017 and documented on video, which uses the self-tracking technologies currently used to monitor online workers and to self-monitor one’s own physical and mental state. By juxtaposing screenshots and webcam footage, the project shows the artist as a representative of a society in which work has become an illness, reflected in the quantification and monitoring of our own performance.

What has been the impact of all this – automation, digitalisation, AI – on jobs like research and curatorship?

It’s a question I often ask myself, but it’s not an easy one to answer. I’ve always believed and said that if I’d been born just ten years earlier, I probably wouldn’t be doing this job. I grew up in the provinces, in a social class which I was in time to hear described as proletariat, before the term disappeared and was replaced by middle class. I belong to a generation that saw the impact of globalisation, communication technologies and low-cost flights at that crucial moment of passage from study to work, when we begin to trace our own course. Without internet and email, it would have been much more difficult, and financially impossible, for me to do my research and interact directly with an international community of artists, institutions and other curators. In this sense, the early stages of digitalisation had a democratising effect, at least on a profession – that of international critic and curator of contemporary art – which until then had been pretty elitist.

To a certain extent, it was electrifying. There was so much information, so many paths open for research, but without the anxiety that would later come from overload, from the impossibility of coping with a shapeless and constant flow; exchanges were intense, but not to the point of detracting from energy available for in-depth study and thinking. Gradually, over the course of the decade that’s about to end, we’ve come to this situation: one in which you’re frantically skimming emails, buying and downloading books you’ll never have time to read, you have fifteen tabs open, you’re tackling several tasks simultaneously, you start the day with a goal but then get overrun with calls and requests.

As for automation and Artificial Intelligence, there’s no doubt that over the years they’ve provided useful tools for delegating curatorship to machines, either wholly or partially. But what interests me, what worries me most is the fact that the invisible and widespread use of AI algorithms in the devices and search engines we use is imprisoning us in information bubbles that are increasingly narrow and constructed for us: suggesting content to view and read, rearranging search results according to our previous searches, adjusting themselves to our automatisms and our preferences.

You seem to be painting a bleak and hopeless picture. Do you believe it’s no longer possible to establish a balanced relationship with work?

Actually, the Hyperemployment exhibition ultimately has a positive message. The last work in the exhibition is Reverie, On the Liberation from Work (2017) by Danilo Correale: it’s an installation that invites spectators to immerse themselves in an extended hypnotherapy session, in which the voice of a professional hypnotherapist guides them to imagine a future without work. For me, this project raises a crucial question: in order to achieve something, we first need to be able to imagine it. Imagining a “post-work” society isn’t easy, because we have to discard centuries of western civilisation in which work was conceived not only as a duty and a necessity, but as a value and a virtue. “Ora et labora”, “work ennobles man”, “work sets you free”, “Italy is a republic founded on labour”: escaping from this default setting means revising our value systems and our social structures. For this reason, even those who have conceptualised a world without work have only been able to think of it as a kind of indescribable and unimaginable promised land. This is why, even though many current circumstances could take us in this direction, all we do is get “hyper-employed”. Correale gives art back one of its functions: that of providing imagination with an architecture, translating an intuition into a clear image, so that others can turn it into reality.

Hyperemployment, curated by Domenico Quaranta, MGLC – International Centre of Graphic Arts, Ljubliana, 07.11.2019 – 19.01.2020

Artisti: Danilo Correale, Elisa Giardina Papa, Sanela Jahić, Silvio Lorusso, Jonas Lund, Michael Mandiberg, Sebastian Schmieg, Guido Segni. The exhibition is produced by Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana as part of a larger programme with the same name, focused on post-work, online labour and automation.

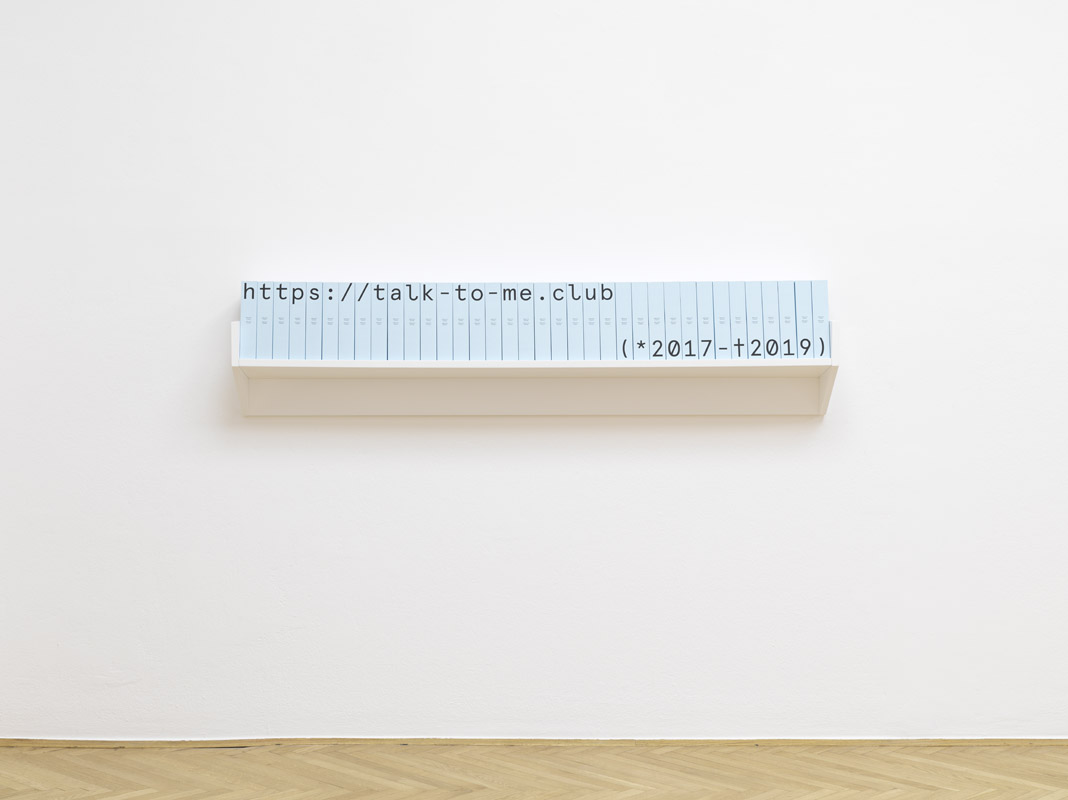

images: (cover 1) Sebastian Schmieg, «Hopes and Deliveries (Survival Creativity)», 2017–2018 (2) Aksioma «Hyperemployment», Poster (3) Silvio Lorusso, «Shouldn’t You Be Working?», 2016 (4) Aksioma,«Hyperemployment», Exhibition view (5) Guido Segni, «Demand Full Laziness», 2018–2023 (6) Aksioma,«Hyperemployment», Exhibition view (7) Jonas Lund, « Talk To Me», 2017–2019 (8) Danilo Correale, «Reverie, On the Liberation from Work», 2017