Works by Luca Vitone come into being from a wide range of cultural interests that focuses particularly on the way in which places are identified though cultural output: art, mapmaking, music, food and architecture. His works are interlaced with various fields of study (anthropology, sociology, geography, music, literature etc.) and incorporated into expressive forms which have always – since his earliest work dating back to the mid-1980s – eluded any canon. Searching the archives is an integral part of a work that sets the project’s design ahead of the finished work. Luca Vitone tells us of his first encounter with popular culture and his interest in it as well as how it has taken shape in his works and what his approach to institutions has been like.

E. G. Rossi: Could you tell us how and where your interest in popular culture began?

L. Vitone: Everything probably started in June of 1964 thanks to a studio recording of popular music taped after a show called Bella Ciao presented by «Il Nuovo Canzoniere Italiano», a musical magazine edited by Roberto Leydi and Filippo Crivelli, for the Spoleto «Festival of Two Worlds». Participating artists included Giovanna Marini, Sandra Mantovani, Il Gruppo Padano di Piàdena, Ivan della Mea, Giovanna Daffini and Michele L. Straniero. The show featured traditional popular Italian music following along a logical thread that aimed at placing emphasis on several musical forms typical of our country: from work songs, political songs, love songs to the stornello folk songs. My parents had the vinyl record album and I used to love listening to it when I was a kid. I began thinking about the relevance of location in regards to our education back in the 1980s and about terms like roots, memory, tradition and identity. I started working on cartography as an exemplary element, as a rulebook of reference for understanding a country. Popular music has always intrigued me and, starting with the aforementioned record, I became familiar with other musical sources thanks to recorded series such as «Dischi del Sole» or the ones released by «Albatros» (my personal favourite). And so I began to get to know popular Italian culture as well as those from abroad. There were ethnomusicologists travelling around the countryside, suburbs, historical town centres, workplaces and the places where people would meet to just relax. They would involve singers and musicians (most of whom were not professionals) who performed this form of essentially oral music and recorded them. I find all this to be very fascinating because it represents a world inevitably destined to vanish or to be transformed, at best. The mere fact that this knowledge is orally handed down from one generation to the next means that every new generation is influenced by their own times and change the «traditional» interpretation. Terms such as tradition, memory, roots, identity and the very same cartography represent an ideological reference of how we wish to interpret the world of yesterday and re-interpret today’s world and that of the future.

I thought this was all so interesting and it inspired me to try and tell the story of our present through mapmaking projects and, later, through music. The gallery has acted as a kind of bandstand since 1989. There used to be a small shelf with a portable cassette tape player on it that played the music. The intention was to place emphasis on how this so-called folk music could bear witness to a time linked to the past and could no longer be a part of the present. As soon as it is performed again, it undergoes inevitable changes related to present circumstances. Moreover music, like food, is an element that allows for the best possible introduction to a culture that is not our own; the approach is direct and authentic. We live with some convictions that history has always been handed down over time. Even at a time when we were speaking of how ideologies were collapsing all around us, the truth is that some were crumbling while others had the opportunity to prevail. Ideology has always involved us and, whether we were aware of it or not, it has oriented our thoughts. This work of mine was an attempt to restore awareness in order to have some control of this ideological interference and understand which our elements of interpretation were; to understand the past and the present and take on the future in a less discordant manner.

Bringing these cultural elements to life through creative forms signified using the most revolutionary exhibit techniques, especially at the beginning of your artistic career. Could you tell us about how your visionary approach met with the art circuit and its system?

I called upon the help of professionals for my projects so they could contribute to the shaping of my work from their specific fields. I have always believed that the main thing that needs to be done is to analyse a disciplinary role and the language. So yes, there was this desire to use music to tell of a culture that was going extinct but also to present a different type of sculpture into the gallery that could only be perceived through sound. Even with the maps positioned on the windows, placed on the floor or hanging in the air, the intention was to find a way of exhibiting my work that did not correspond to the standard of the times. In those days, my point of reference was the experiences of the preceding decades – those more closely linked to an analytical interpretation of art. I tried to advance an approach to exhibiting that was based on tradition and, if possible, change the devices used. I was in my twenties when I began my first professional relationship with an art gallery. Obviously, there were new galleries who dedicated a lot of space to research. I have to say that it was difficult back then to approach many institutes; contemporary art museums were practically inexistent in Italy. When I started out there were only two: the Castello di Rivoli (since 1984), which started working with my generation about ten years later, and the Peccei (since 1988). Exhibits were held at private galleries or random places, thanks to the participation of a curator of some administration or a private collector.

Your creative work is always complemented with an exchange and constant dialogue with professionals from different fields. Speaking of which, you have worked with anthropologist Franco La Cecla. Together you published a book, «Non è cosa. Vita affettiva degli oggetti – Non siamo mai stati soli» (It’s not a thing. The emotional life of objects – We have never been alone). Could you tell us about this collaboration and how this book was later converted into a workshop at the MAXXI museum?

Collaborations with people from other professional spheres is to be considered as personal maturation and, as I mentioned earlier, a strategy for creating works and creating an exchange with the exhibit space. My collaboration with Franco La Cecla started fifteen years ago. I began reading his books in the early 90s and his first one, Perdersi. L’Uomo senza ambiente (Getting Lost. Man without Environment) is a small masterpiece in Anthropology that really captivated me. In 1994, while working on a series of fifteen works that explored the role of objects in our lives, I wanted to meet him and ask him to collaborate with me by writing a catalogue for an exhibit being hosted at a private gallery. I decided not to publish it, though. At that point, I refused to exhibit these works and they were presented in various group exhibits. During that time, for other reasons, I met the editors at Elèuthera – where Franco had already published Pensare altrimenti (Thinking otherwise) – and they put me in touch with him. After that, they invited us to resume the project and do a book together which was published for the first time in 1998. This collection of essays by Franco analyzing the role of objects in human relations is accompanied by images of my work and a brief text I wrote. It met with success and we are now in our fourth edition. For the occasion I exhibited a selection of works belonging to a project from a personal show in a gallery in Milan where, at a later date, we presented a book with Grazioli and Belpoliti and organized a concert for objects performed by a small percussion ensemble directed by Elio Marchesini. While speaking with Anna Mattirolo in Rome, the idea came up to present the book at the MAXXI as well. Thanks to Stefania Vannini, that invitation brought on an offer to present a workshop for families and since we had never done anything like that before, we accepted on the spot. I had held enough workshops for participants of many ages and types, but only on an individual basis. This idea of involving families hadn’t come along yet and it seemed to be a fantastic brainchild because objects gather intimacy and family memories. So we invited three different generations: grandparents, parents and grandchildren and they all brought items that were not precious in the monetary sense – something not to be taken lightly but it did confirm our idea. An object is a condenser of our thoughts, linked to the people who keep it and is handed down from one generation to the next or, if purchased directly, is a souvenir of an important event. It was interesting to listen to and compare the different ways the participants related to an object while talking about it – the difference in viewpoints between grandchild and grandparent, parent and child or even boy and girl. A was a day filled with stories. Franco has a lot of experience there. He’s a great storyteller and he told many fun and interesting stories, even about faraway cultures. After the workshop, the book was presented in the gallery on the top floor of the museum. With us and the representatives of the museum were the Garrera twins – Gianni and Giuseppe – who were really brilliant. It was the Giorno del Contemporaneo (Contemporary Day), the room was packed and the evening was a triumph.

Among the numerous events – going on now and planned for the future – that feature your works, there is also the exhibit in Bolzano curated by Letizia Ragaglia: Collezionare per un domani. Nuove opere a Museion (Collecting for a day in the future. New works at Museion). Could you tell us about your work for collectors? Are there any particular clauses for public or private collectors (for instance, regarding their conservation) in cases of works that include short-lived components?

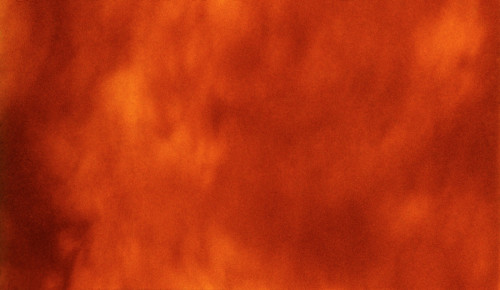

I’ve got two works as part of the collection at Museion. The first, Le ceneri di Milano [The Ashes of Milan], was purchased for the inauguration exhibit at the museum’s new location under the direction of Corinne Diserens in 2008 – part of a series of monochromatic works created with the ashes from a waste-to-energy plant in Milan for the occasion of an exhibit by Emi Fontana in 2007 – and the second, Rogo [Pyre] was produced and acquired upon Letizia Ragaglia’s request for a solo exhibit Monocromo – Variationen, held in 2012: a 16 mm film that features close-ups of the fire at the waste-to-energy plant in Bolzano. This too is a monochrome dedicated to ashes and waste. In regards to the second half of your question, I would say that the clauses for conservation are based on common sense above all else. In some cases, there are some preventative rules to follow that are agreed upon during the purchase. The safeguard of the material property of the work is entrusted to the responsibility of the institution. Museion and other public or private institutions generally adopt a very careful control system that rarely makes errors. Short-lived components are a constant in today’s artistic production and, besides the fact that the materials used will become increasingly perishable over time and will call for even closer attention, they often need some kind of maintenance in order to keep them functioning properly. In some cases the ingredients need to be integrated so that the work can be activated.

«Collezionare per un domani. Nuove opere a Museion», a cura di Letizia Ragaglia, Museion, Bolzano, group show, March 21st, 2015 – January10, 2016, this interview was translated from the original Italian version that appeared on the Italian art magazine Exibart.com on April 24, 2015

[nggallery id=69]

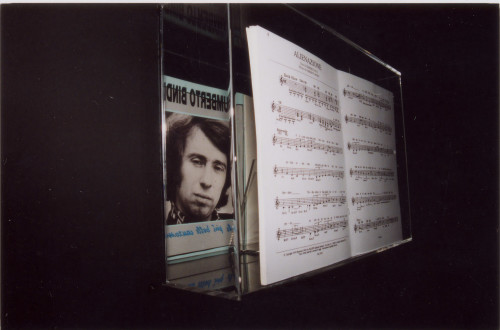

Images (cover and 1) Memorabilia (Alienazione), 2002, case in plexiglas and mirror with score, 35 x 50 x 12 cm, 1 of edition of 3, photo by Shobha, Micromuseum’s collection, Palermo, Italy, courtesy of the Artist (2) Polimnia, 2001, stool,accordion, electric wired, yellow and blue lights, variable dimensions, Renato Alpegiani’s collection, Turin, Italy (3) Eppur si muove (Cartolina), 2003, 1 of 6 postcards – 10 x 15 cm., courtesy of the Artist (4) Liberi tutti! (Elèuthera, Carrara), 1997, color photography, photo by Luca Vitone, courtesy of the Artist (5) Rogo, 2012, still from video, projection from Proiezione Super 16 mm film, 2’ 22’’ Loop, courtesy Luca Vitone and Museion Museum, Bolzano, Italy.