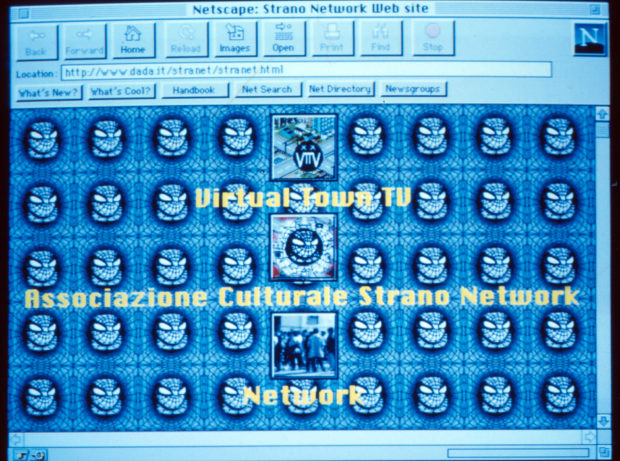

Tommaso Tozzi is an artist, activist and theorist active in the underground culture since the ’70s within the underground culture and he pioneered net activism in the pre-web era. Tozzi is among the founders of several independent artistic and social computer networks and online sites aimed at art, culture and the construction of independent virtual communities, as well as archiving and mapping projects related to alternative cultures. He is the author of er arter Art BBS (1990), cofounder of the Cyberpunk (1991) and Cybernet (1993) networks, Strano Network (1993), Virtual Town TV (1994) and the site Strano Network (1995). In 1995 he launched the first global Netstrike, a strike orchestrated ‘with’ and ‘on’ the net, organised with Strano Network to protest against the French nuclear tests in Moruroa. Tozzi created and designed theHacker Art site (2000) and the Hacker Art Archive (2002). Recently he also created and launched the project Wikiartpedia – The free online encyclopaedia of network art and culture (2004) that received the Honorary Mention Prix Ars Electronica 2009 – Digital Communities (today accessible as EdueEda). In conversation with Matteo Pompili, a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, Tommaso Tozzi retraces his artistic journey and explores possible present and future scenarios.

Matteo Pompili: You coined the term ‘Hacker Art’ and started to work productively in this field over twenty years ago. In the meantime, this field has experienced a period of natural decline. Many consider Hacker Art to be over, in the same way that everything in the field of Net Art is thought to have already been done. Do you agree with this view? In your opinion, what is or what might be the role of Net Art and Hacker Art, and their corresponding applications, in the current landscape?

Tommaso Tozzi: I have personally used the label Net Art only for reasons of convenience.

When I presented a selection of new disciplines to the Ministry, through my then Director at the Carrara Fine Arts Academy, Professor Marco Baudinelli, I proposed the disciplines “Net Art” and “Hacker Art” for these to be included in the new Ministerial statements concerning what would later be labelled as New Technologies for Art, assuming at the time that it would unlikely for Hacker Art to be accepted. This was back in 2004 and I had been working as Coordinator of the newly founded School of New Technologies for Art since 2003. At the time I had to come up with a new design for the old course in Multimedia Art established in 1999 by Professor Andrea Balzola together with the then Director, Carlo Bordoni. This was because we were transitioning from the old four-year degree to the system of 3 + 2 years. In doing this I began a long collective conversation with other lecturers working in the Multimedia sector of the Carrara Fine Arts Academy, along with other colleagues who were also coordinating the field of Multimedia in Italy. The three-year degree in Multimedia Art at Carrara was launched during the academic year 2003-2004. In 2004-2005 I set out an initial proposal for the two-year course, but this was immediately interrupted because CNAM did not give its approval. In 2007, after some essential changes to ensure the Study Plan followed ministerial guidelines, I re-proposed the project which was finally approved in November, through a Ministerial Decree, under the title Biennio in Net Art and Digital Cultures, to be taught within the School of New Technologies for Art. The disciplines I had previously suggested and that had been included in the first version of the Ministerial statements (finally formalised in 2009) became part of this course. Among these, the Net Art module was to be found. Naturally no Hacker Art discipline would have been authorised by the Ministry, so I had to accept the different label. However, I always tried to develop, both as coordinator and lecturer, the meaning that I had given to the term “Hacker Art”. In this way, over the years, I have been able – in both the three-year course in Multimedia Art and in the new two-year degree in Net Art and Digital Cultures – to include colleagues who were engaged in social hacking, self-management, auto-production and counterculture as teachers: Ermanno “Gomma” Guarneri, Maurizio Lucchini, Enrico Bisenzi, Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Stefano Bettini, Marco Cesare-Consumi, Alessandro Ludovico, Vittorio Zibordi and Arturo Di Corinto, or attentive critics like Gabriele Perretta and Pier Luigi Capucci, and many others. Since 2011 the new management has, bit by bit, successfully dismantled what had been built, leaving only a few traces of the original programme. At first meanings were given to Net Art, as practiced in Carrara, that did not always correspond to such a term: social features, struggles for a new economic model focusing on shared knowledge and goods, rejection of commercial logic, defence of oppressed social classes and citizens’ freedom and rights. All these are often left out of the poetics of so-called Net Art, at least in the way it is presented by historical scholarship. It was, therefore, a question of reinterpreting the meaning of Net Art, and taking it in other directions. Whereas the old management in Carrara favoured the figure of artists who immersed themselves in the problems and contradictions of society in order to imagine a new system of relations within it, the new management repositioned the artist on a marble pedestal.

Net Art was the label that came closest to such objectives.

But labels are valued by historians and those who want to establish a precise theoretical objective, often including supremacy, whereas their value decreases when defining a meaning which is actually connected to people – their individual and collective action.

Since 1989 I have personally associated myself with the term Hacker Art because I saw, and still see, in its ethics an action free from the interests of the current art system. I have already tried elsewhere to explain what I meant and mean by such a term, but the ability to communicate the spiritual element that underpins my choice has always eluded me. As far as I’m concerned, Hacker Art represents an attitude emerging from the spirit, from the spirit’s desire to mix with surrounding souls. My dear friend Buonarroti taught me to appreciate the element that surrealism would later consider as the “spirit’s uprising”. A sincere Christian faith invokes, within the current Catholic landscape, the “spirit’s uprising”. Whereas the struggles of Workers’ Unions try to give a material dimension to various spiritual demands, art attempts to unite them with demands that rest on an exclusively spiritual level, invisible to us, intangible, not part of our senses but nonetheless alive. This art doesn’t remain outside the living flesh of social and material problems, but immerses itself in these and re-emerges thanks to the union of soul and spirit. The computer network has been an attempt to give a collective spirit to this dimension, the union of souls, a place to inhabit. Technology is neither a tool servicing tradition, nor the guiding light of a new form of economic and technological dominance, but a new space in which this union of people and the spirit’s uprising can live. The network space, however, is extensive, moving through minds and cables to enter our everyday lives and our physical and real daily actions.

The twentieth century clearly outlined the demand for a new art space, not only as a material object but also linked to the everyday flow of events. With this direction in mind, Hacker Art tried to identify a new place in the computer network and its encounter with real life, a new place that enabled a collective rebellion of people to emerge.

A place where love for others can be recovered and the rejection of every form of dominance, injustice and abuse of power, both material and spiritual, is nourished. An uprising that is expected and towards which we are moving.

I find it difficult to define and separate life with a word: Hacker Art. It is also difficult to differentiate between the Hacker Art I created and what emerged from simple everyday life. Consequently, I cannot say whether Hacker Art or Net Art is dead, when the people who embody this vision are still physically around. It is even harder for me to imagine a future in which their souls are not manifested in other objects and subjects. This doesn’t only apply to Hacker Art and Net Art, but to every object and aesthetic movement.

Rather, it is easier for me to image the role of Hacker Art in the present landscape as allowing every moment of our lives to become the place where our souls’ union and the spirit’s rebellion occurs.

How important is Hacker Art in the ways political action is planned?

Hacker Art helped people meet and recognise their mutual collective demands. It tried to offer tools that would enable this alternation of voices to become a single choir. It tried to advance the possibility for the network to be a new place in which induced social roles were not already predetermined, in which there were no hierarchies or masters to bow down to or norms imposed on the basis of a specific set of privileges. A horizontal web, organised bottom-up. Hacker Art tried to give visibility to a new way of political, economic and social action: a small drop in a centuries-old struggle.

What was the relationship between Hacker Art and the art system? And what is this relationship now?

I tried to give these models visibility within the official art system through solo and collective exhibitions in galleries and museums.

Hacker Art is made by people, not by single artists; it’s not an object created by someone, but an ongoing social model represented by a term through which its meaning is given. This isn’t my model; I only tried to give a new name to a centuries-old position which already existed. I tried to give the documents and publicity surrounding these models access to the art system in order to maintain a unique social model outside the market. The result has been more or less a failure: the product, the model hasn’t been understood, except for a small group of people who didn’t need convincing in the first place.

Hacker Art has fared better outside the art system: in moving networks, as well as education. It has spread in these fields and continues to grow through infinite currents that are completely separate from Hacker Art itself.

It’s easier to create Hacker Art through the act of embracing one’s daughter than through an exhibition in a gallery.

What has your relationship been with other artists close to Hacker Art over the years?

I found harmony with movements, intellectuals and people of sincere faith. In other words, people who didn’t define themselves as artists but who I considered to be artists more than many others.

I found myself agreeing with artists when we left our identity as artists behind us. With some I have worked as a group and these have been wonderful encounters, from which each one of us has benefitted and gained experience but, I repeat, this happened during group work outside the official art system.

It’s rare for me to meet people with whom I can collaborate within the art system who, in my opinion, express their artistic qualities in the context of Hacker Art in a dignified way. Among these there are some who I greatly admire, Giuseppe Chiari for example. They haven’t, however, become close to Hacker Art. On the contrary, it’s the term Hacker Art that has tried to expand its meaning by drawing on what was good in their creations.

In 1997 you turned down the allocated money for the Gallarate Prize, donating it instead to the activities of the website “Isole nella Rete” (“Network Islands”) in order to bolster them. On this issue, forgive my pun, how important is it to build “a network” between various projects that want to use art as a tool to organise political action?

With this donation I wanted to make clear that the official role of the artist had to change: from a producer of goods to a mediator who transfers resources.

This idea emerged from noticing that the best art proposals were taking place outside of the art system and that the official art system was only able to produce, almost exclusively, money and visibility. It was supported by a cultural system and the political management of this sector that followed customer logic, in a more or less exclusive way, and which did not favour the best potential offered in the field.

As a result I foresaw the possibility that the role of the artist could replace the political role of various cultural administrations, including museums – in other words, places able to offer resources to the art world – to become mediators able to reorientate the flow of resources towards the most deserving places.

As a form of mediation in human relationships, money represents the real problem. But mutual solidarity is the real resource, not money. At the basis of this operation, therefore, I believe weight must be given to the attempt to reconsider the need for the substitution of the production of objects/symbolic mediators, which are the material art works, with a move towards a spiritual and disinterested act of giving towards others. To try and answer your question: the need to build a network, from this point of view, has to be equated with the need for every human being to be drawn to others.

The founding principle of your work Hacker Art BBS was to make art digitally accessible. Do you think these acts are still needed today?

If by “Art” you mean the creation of relationships, the ability to give meaning and give others the possibility to make sense of reality in autonomous ways, as well as all the other things previously mentioned and many others still to be discussed, then I agree that this was the basic principle underlying Hacker Art BBS and that it is still necessary to do this today, both online and in real life.

If, on the other hand, you understand BBS as a place where an image, a sound or a musical composition can be accessed in digital format, then I would have to disagree with you that this was the founding premise for BBS. These are things that are undoubtedly necessary and useful, even with the aim of transforming the current economic and social model, but this was not the basic principle. This was simply one of the many shapes that the index finger assumed when pointing towards the moon. The moon, however, was something else entirely.

Is the idea of achieving a Net Strike feasible today?

Yes, but not online, rather in the everyday refusal to submit to any form of dominance.

We do not need to engage with broadband, but with spaces of everyday life. The more we engage with these, the more Life Strike will work.

What advice would you give young artists who want to combine their artistic journey with the world of technology?

First of all, search in your souls and those of other people. Only later can you try to see how technology can become a space which people can inhabit and the ways in which this can be achieved.

Tommaso Tozzi

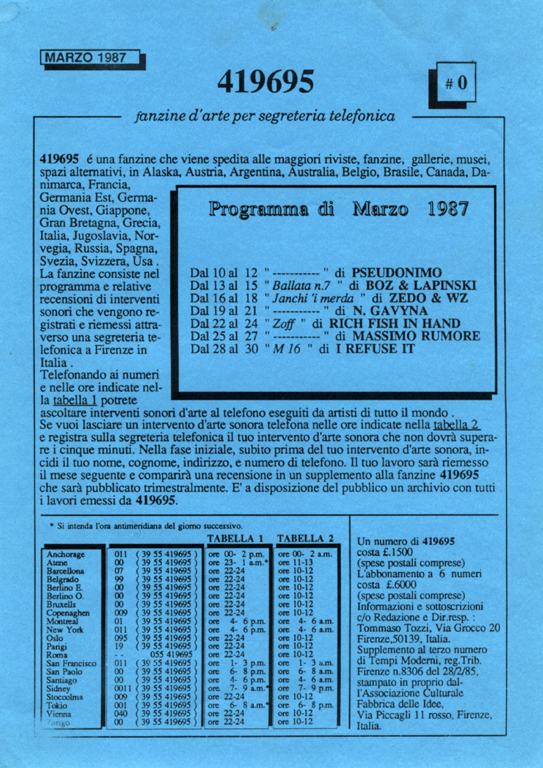

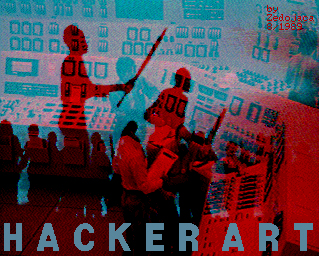

images: (cover 1) Adesivo ‘Hacker Art’ with subliminal writing “Rebel!” by Tommaso Tozzi, within a mail art collettive work realized by another artist (2) Tommaso Tozzi, 419695 – art fanzine for telephonic machine, 1987 (3) Tommaso Tozzi, «Hacker art», 1989 (4) Tommaso Tozzi, multimedia installation inside the elevator, collettive exhibition «Soggetto Soggetto», curated by Francesca Pasini and Giorgio Verzotti, Castello di Rivoli, Torino, 1994 (5) Tommaso Tozzi, «Hacker Art BBS», 1990, presentation at C.S.A. Ex-Emerson in 1993, video documentation from youtube (6) Tommaso Tozzi (conceived and coordinated by), «Happening digitali interattivi», 1992; Collective music by: Giuseppe Chiari, Tommaso Tozzi, Ludus Pinsky, Messina (Radio Gladio), Lion Horse Posse, Tax (Negazione), FM (Pankow), Simonetta Fadda, Roberto Costantino “Le Role”, M.G.Z. (Far), Alessia/Andrea Avanzini, Helena Velena (Cybercore), Gaiani, Trans xxx, Marco Cesare (Juggernaut), De Luca, Fantin, Denni (Gronge), Michele Mariano, Mercuri, R.N., Steve Rozz, “Chip” Boni, Massimo Cittadini, Mikeletron, gli utenti di Hacker Art BBS, Bertoni & Serotti, Le Forbici di Manitù, Luca Pangrazzi, Pedro Riz a Porta, Nannelli, Andrea Marescalchi, Carlo Nati, Maurizio Montini, Antonio Glessi (Giovanotti Mondani Meccanici), Musica & Immagine, Leddi (Stormy Six); Collective texts by: Agenzia di comunicazione antagonista, Vittore Baroni (Rumore), Bedini (Gronge), Carlo Branzaglia, Tsche@Streik (Officine Schwartz), Mace (Trap magazine), Roberto Marchioro (Amen), Luigi and Oliver (Nautilus – Lega dei Furiosi), Gabriele Perretta, Marco Philopat (Decoder), Roberto Pinto, Spalck (Pankow), Francesca Storai, Angela Valcavi (Informe), Paolo Vitolo, Gabriele Bramante (Wide Records), Andrea Zingoni (Giovanotti Mondani Meccanici) Self-produced by Tommaso Tozzi in collaboration with Leonardi V-idea, Neon, Silab, Paolo Vitolo, Wide Records; essays by: Tommaso Tozzi, Vittore Baroni, Giuseppe Chiari, Jumpy Velena, Gabriele Bramante, Raf Valvola, Damsterdammned, Centro di Comunicazione Antagonista, Gabriele Perretta, SolowMace – Trap Magazine, Paolo Vitolo, Marco Bedini, Per Nautilus: Luigi and Oliver, Massimo Cittadini, Marco Philopat for Cox 18 (7) Tommaso Tozzi, «Strano Network», website, 1994 (8) Tomaso Tozzi, «La politica si fa anche senza armi, L’arte si fa anche senza le gallerie», Florence, 1990 (9) Tommaso Tozzi, «Cellule sociali», 2008