It is with pleasure that Arshake releases today the second of four parts of the interview between Victoria Vesna and art historian Dobrila Denegri, currently Art Director of the Torun Center of Contemporary Art (Poland). The interview has started in 2005 and continued throughout time as far as today, on different occasions, between Rome, Los Angeles and Torun. In this dialogue, Vesna recalls her pioneering projects which were carried out at a time when «database aesthetics» were pretty much a visionary phenomenon and the role of nano-technology was not as a recognized as it is today, moreover when into the artistic sphere. In the last part of the interview, she talks about some of her recent projects, such as Blue Morph and Hoz Zodiac. Her research pushes forward the analysis of organizational structure of data, examined along with the way they shape language, how they direct the communication processes. She detects morphological elements that are common to different species while monitoring and studying the metamorphosis processes. Yet, again, science and art are intertwined with cultural factors. Furthermore, Vesna recalls the beginnings of her famous collaboration with nano-systems scientist Jim Gimzewki that started back in 2001 (still in progress), as well as the ones more recently established with neuro-scientist Siddhart Ramakrishnan and evolutionary biologist Charles Taylor. The first part of the interview was published on Arshake April the 3d, 2014.

Dobrila Denegri: So through works like No Time, Datamining Bodies, Cellular Trans Actions and references to Buckminster Fuller we came closer to the issue of Nano science and your more recent work. So, how it all started, what triggered your interest in nano technology?

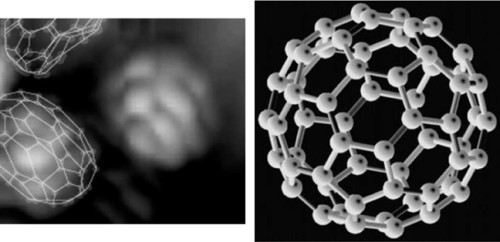

Victoria Vesna: In 2001 I was organizing a panel discussion called «From Networks to Nanosystems» that was a response not only to the idea of nanotech but also the news that the California NanoSystems Institute (CNSI) was going to be built on campus. This was a month after 9/11 and I was curious not only about the relationship between art and nano science, but also to explore the role of artists and scientists in this new era. I was excited about this idea but very few persons showed up, mainly because not too many people knew yet about nanotech and also because it is a world beyond the visual realm. Any time I would mention this, almost automatically the response was: ‘why would we make this relationship between nano science and art at all’? But, I have to say that in retrospect, the few people there were critical and understood the immense paradigmic shift that was happening due to this new science. Namely, my professor, Roy Ascott showed up with his research group and he really shared the excitement. For instance, if you try to observe relationships between art and biotechnology there is no problem, but nano? I insisted on having scientists on this panel, because to have just artists’ talking about art and nano-science would have remained in theoretical or purely speculative realm. After getting lukewarm responses from a few scientists, a friend introduced me to Jim Gimzewski who just arrived to UCLA from IBM Zürich. I was delighted to get an immediate positive response from him and was amazed to see that his research was what I was reading about and that he even had some of the same slides in his presentation – but from completely different angle! He was working with Buckyballs but never heard of Buckminster Fuller, so we immediately started with a very interesting exchange of ideas that turned into a prolific collaboration that continues to this day.

Nano, as the dimension beyond visual realm, in connection to art, what kind of paradigm shift is it announcing?

First of all, let me try to describe the proportions of nano scale which are really beyond the visual realm, or rather, beyond optical microscopy. The word «nano» comes from the Greek word for dwarf and a nanometer is one billionth of a meter, approximately 80,000 times thinner than a human hair. The way Jim described it to me was by showing a scale where an atom is like a golf ball, a human finger like Eifel tower. In order to manipulate matter this small, nanoscientists, chemists like Gimzewski but also others, use the Scanning Tunneling Microscope, or STM, that in fact he and his team built. The instrument does see the nanoparticles, it feels the surface of the molecule, and moves them around with an atomic size probe. You could imagine this as a record player moving across the grooves and sending out data of the terrain. So first thing that is important is that you are feeling the molecular surface before you are able to visualise it — this is a big difference in the way we are getting information. It represents a really important shift from seeing to feeling. Most of our culture, and certainly our art culture, is about seeing. In our daily lives, we are used to make judgments about someone’s look, clothes, cars and other commodities based on seeing, so now, to think that feeling could be the first step seems to me as a big leap. The second paradigm shift that nano brings is that it introduces principle of «bottom – up» which is exactly the principle how the nature works. It is the opposite procedure to the one we are using in our technological development, that is «top – down». We started with big computers, and tried to make them smaller and smaller until we reach ridiculously small, and than we reached the limit. But if we go «bottom up», we do not reach the point at which we are forced to stop in the same way and «top down», as dominating principle of materialistic thinking, or of our political or social systems is not functioning so well any more. We can testify that everything concerning our political or administrative systems is falling apart and getting decentralised. What functions, on the other hand, are smaller groups that are coming together and linking up in the network. So «bottom up» is another important paradigm shift.

When you try to see, or actually to feel these small particles, what is that we actually realise?

We have to have in mind that we are made of atoms and molecules, that all around us is also made of atoms and molecules, even the most solid matter. And when you go so deep into the structure of the matter you realise that there is nothing solid, at least not in the way we are used to think of solid, there are just electron waves. What you realise is that there is actually empty space. This is so poetic, so buddhistic! Scientists rarely perceive this poetry, but for me, as an artist, it is amazing to work with this unknown territory. Nano science is only on the beginning, so there is so much still to be discovered. But one thing is sure, that nano will revolutionise our future.

Your role, as the artist, is in a way to «translate» in visual forms what scientists are working on, since they still seem to lack verbal or visual instruments to explain it properly?

Visual and auditory too – I am interested in making the invisible visible, the inaudible audible. It is amazing to me to see that scientists often use the lexicon of science fiction movies for describing some of their research. What I realised is that we have still vocabulary of industrial age applied to the totally new age that is unfolding in front of us and for which we have to find new definitions. This new period is totally dematerialised but this whole idea about empty space is still too foreign to us.

This leads us to the «NANO» show that was held for the first time in LACMA – Los Angeles County Museum. With this show you tried to use tools of art to «visualize» some scientific concepts. How was the approach of the institution towards this collaborative project between you and nano scientist Jim Gimzewski? How you approached it’s realisation?

I should mention that this large exhibition that includes seven installations in a custom architectural space is installed until 2011 at the Singapore Science Museum and most recently was exhibited at the FAAP museum in Sao Paolo Brazil with astonishing success. This is a relatively conservative museum and they had a record number of people visit – 164,000 during the 50 days that it was on show. The installations can be shown separately and they certainly have been travelling the world, all over Europe, Korea, China, India… But it all started 5 years ago when we were given a unique opportunity by LACMA to be «experimental space» or laboratory. This was due to a programming vacuum that happened when the proposed renovation by Rem Koolhaas fell through – I really don’t think they would have ever taken this kind of risk in museum «business as usual» that plans so much in advance. So, it was probably meant to be and we put together a fantastic team from the media arts, sciences and even humanities. We worked with the architectural office of Johnston Marklee and Katherine Hayles who published a book about the subject in process and contributed text to the exhibition.

At the beginning it was not easy, we didn’t start to work in team, but soon we understood that the only way to make this exhibition properly, was to sit on the same table and work out things together. I really believe in collaboration and sort of «collective» intelligence. Exhibition, as the outcome of this process was like a collective/collaborative piece, as well as a hybrid of media arts, sculpture, architecture and science. But at the first we would explain how we imagined installations and architects would go in their studio and project the spaces. I felt quite uncomfortable with the idea of «filling» predisposed spaces with installations, projections and sounds and envisioned a more organic installation. The architects were inspired by this as well and came up with a brilliant plan to construct the show on the basis of the Buckminister Fuller’s Dymaxion Map. It is probably most precise world map ever made, because it is not just transposition of the sphere to the bidimensional rectangle which causes distortions of continents. Dymaxion Map has been realised empirically and it deconstructs the sphere of the globe in the series of triangles, leaving proportions and shapes of the continents untouched. For Buckminister Fuller was exactly the creation of this map, mathematical calculations and geometrical notions, that opened the path towards realisation of geodesic domes. The idea was fascinating for me, because we were suppose to construct the show about nano, about so small scale, using as the base map of our globe. It was good way to challenge peoples’ perception of scale. We really can’t imagine molecular world, not even scientists can; but also, we can’t imagine how big is our planet in relation to us. Both are such abstractions. But they didn’t just take the Dymaxion Map as it is, they broke it up, so it would correspond to the position of installations.

Talking about nano science, nano technology, one starts to think automatically about the technology you have been using for the show. How complex was this exhibition from the technological point of view?

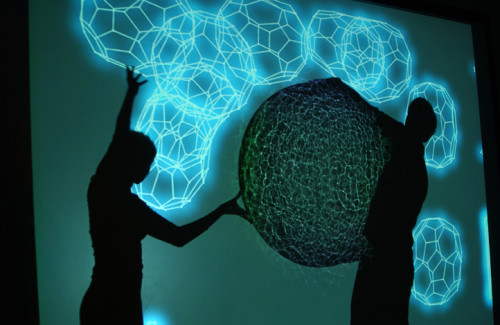

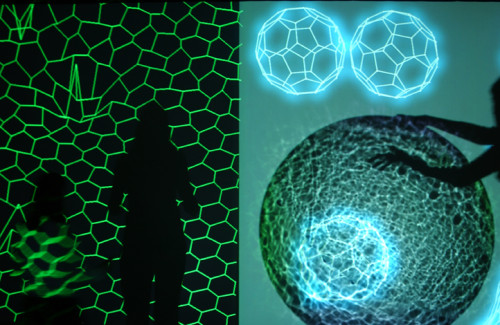

During the realisation of inner architecture of the exhibition we decided to hide all the technology, to place it behind the walls that we were constructing. Just because the exhibition was dealing with nano, with notion of advanced science and technology, and in fact, since we are living in more and more technocratic society, it seemed important to create a space, as light as possible, from the technological point of view. So we made it in a way that, when the space was empty, it would be totally silent and still. Nothing would happen until a person would step in. At that point the space would start to get animated; images and sounds would start to appear, and observer would be immersed into the world of interactive projections that would change with their behaviour. The presence of audience, or even of a single person would ‘light up’ the show, would cause the change of the space, and than would be able to continue to transform the shapes of the projections, just by moving of the body, or shadow, or by the voice. It was very important to shift the perception of the space of the public. For example, one could manipulate the shape of the Buckyballs by his or hers shadow; and it is a very interesting and strange feeling, to do something over there, to change a shape of the projected molecule with a silhouette of your body and with very slow motions.

On the other hand, in spite of the fact that the show was about science and new technology, we used a lot of very «low tech» devices, but producing effects that were very engaging, even if done in a very simple way, kaleidoscopes were very effective for example. This orientation toward some “low tech” solutions was motivated also by the practical reasons, such as duration of the show or interactivity. Exhibition was on for ten months, open six days a week, which is really long period for contemporary art show. Amount of public was huge, few hundreds of thousands of visitors, coming from really very different cultural backgrounds, professions or of different ages. Concerning interactivity, it is amazing with what kind of aggressiveness and violence people act when they think they should interact with the exhibited pieces, so we had to repair and substitute parts of installations various times. Of course for this reason, less technologically complicated solutions, worked better. Later, this entire installation was at the Singapore Science museum and it ran for a period of five years with very little technological problems so it was a good learning experience.

This work, where public was manipulating the projected shape of molecule with own shadow, was on the entrance of the museum. It was the first contact with this nano world. What molecule you used and in what kind if interaction you engaged the audience?

Since the show was in Los Angeles we thought that the molecule of carbon dioxide would be more appropriated. We wanted to visualise, as precise as possible, the procedure of manipulation of the molecule that scientists are executing in their laboratories. What we discovered is that if they push molecules with force, nothing happens. The same rule was applied for interaction with projected molecules, Buckyballs: if you wanted to play with their shape, to change them, you had to move very slowly, like in some kind of slow-motion dance. It means that if you go very, very slowly you can effect a lot of change. I think it is a big thing to shift the idea of interaction in sense that a slow movement makes things actually happen. No more fast and instant gratifications; no more violent gestures. It is interaction that you do not expect, or you are not used to. Visitors had to «learn» how to interact because we really didn’t want to explain or teach anything.

Exhibition was in permanent change during the time of its duration?

Yes, some parts we would redesign, change, transform. It was like constant work in progress. For instance, the floor projections we redesigned few times. They really were causing strange effect, almost altering the sense of orientation and gravity.

This floor projection was part of the central installation. How it functioned as a whole?

Installation was called Inner Cell and functioned as an analogy with nano space. We used pervasive computing techniques (camera tracking, floor robots, multiple projections and focused sound) to create an immersive environment that was suppose to elicit «chemistry» between the human visitors, exhibition robots and molecular representations. Inside the cell, beside large-scale projection of Buckyballs that were programmed, as I already mentioned, to respond to the touch of the visitor’s shadow, there was the large floor projection that would move under the feet of the visitors provoking a feeling of constant motion of «gravity waves» that would also set off sound effects. The main sound feature of the inner cell was a strong, rumbling bass, which was synchronized with the motion projection of the hexagonal grid onto the floor. The visitor’s movement in the cell space would influence the sound, as well as the visual grid projection on the floor. The interactive Buckyballs projected onto the cell’s walls would emit a chiming sound that complements the bass frequency. Also within the cell, the robotic, moveable balls would produce a high-pitch sound that was distinct from but complementary to the other sounds in the inner cell.

You have been guiding us through zones of emptiness and fluidity by talking about nano, about scale beyond visible realm, about electric waves, primacy of feeling instead of seeing. What about hearing? Could you tell us more about sound, about audio effects that played equally important role as the visual part in the exhibition?

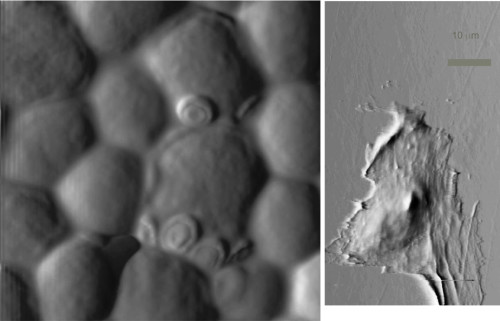

We used for the first time some of new research of Jim Gimzewski and his team to create the «sound» of the show. Jim and his group used the instruments for measurement of molecular surface to the living yeast cells, and so they detected the movement of them, which is really imperceptible, but still, possible to trace since every cell is moving on a different frequency. This research has been published in Nature and had great implications. It proves that you can hear if a cell is dead or alive or distinguish different sounds belonging to the different types of the cells. So we took some of these sounds, accelerated and amplified them so humans could hear and composed with the living cells a sort of «ambient» sound.

In this show you linked up futuristic scientific vision with eastern spirituality. How this occurred?

Nanomandala was about «bottom up» principle that is present in the process of creation of mandala. This installation showed how Eastern and Western cultures use these bottom-up building practices with very different perceptions and purposes. This installation incorporated a mandala, a cosmic diagram and ritualistic symbol of the universe, used in Hinduism and Buddhism, which can be translated from Sanskrit as «whole», «circle» or «zero».

The curator asked us to select artwork from the contemporary art collection to include in the NANO exhibition – in order to make some kind of connection. I remember going many times and looking around, not being able to really find a piece that would fit in well. Then I thought. ‘we are working with the idea of empty space, so something from the East Asian collection would work better’. As it happened, the director of the collection loved the idea and told us about the sand mandala that was going to be constructed at the same time by Tibetan monks from the Ghaden Lhopa monastery in India. We met with the monks many times before starting to work with them and realized that the one thing we shared in our intent was to show how everything is interconnected.

Creation of mandala starts with one grain of sand and than expands to very complex universe. The monks were building the Chakrasmavara mandala that was very complex and took four weeks, all day long with four monks at a time painstakingly working with the colored sand. Observing them at work was not very different from watching the scientists working with the molecules and I was very inspired. Of course the real challenge was how to make sure that this does not simply take advantage of their work but is an actual art /science/monk collaboration. There are three views of the mandala that is projected on a bed of white sand – photographic, optical and beyond visual with the scanning electron microscope. All together we took 300,000 individual frames that resulted in a zoom from inside a grain of sand to the entire complex image that was the same size as the original mandala.

This is all to illustrate that at every stage, from the grain of sand to the entire complex mandala, the images contained the same amount of information in order to create a visual effect of ascending up and zooming all the way in, beyond the powers of ten. The nanomandala zoom is projected on a round bed of sand that is same size as the original sand mandala and the piece becomes a meditation on the importance of every particle and wave, of the interconnectivity of all of us, and everything surrounding us, and on our amazing ability to take huge data-sets of information and reduce them to the essential truth in the blink of an eye. It took billions of sand grains to construct the complex sand mandala but now we know and can see that each grain of sand has many billions of molecules in its’ composition. After a certain amount of time, the sand mandala was swept away by the monks and ceremoniously thrown into the ocean. In the case of the nanomandala, the computer and projector are shut off and only the memory in our minds remains.

images

(cover) Victoria Vesna, Nanomandala, snap shot (1) «From Networks to Nanosystems 9/11-N2N: Art, Science and Technology in Times of Crisis», UCDARNet Conference. University of California, Los Angeles. November 28, poster, 2001 (2) Bucky Balls (3) yeast cells (4) Victoria Vesna, Quantum Tunneling, Media Art Laboratory, Graz, Austria, 2008 (5-6-7) Victoria Vesna and James Gimzewski, Zero @Wavefunction, «NANO» exhibition at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2003-2004 (8) Victoria Vesna, Nanomandala, 2005 (9) monk at work for the Chakrasmavara mandala (9) Victoria Vesna, Nanomandala, Studio Stefania Miscetti, Roma 2005.