«For you can tie me up if you wish/but there is nothing more useless than an organ/When you will have made him a body without organs/then you will have delivered him from all his automatic reactions/and restored him to his true freedom (…)». These words were spoken by Antonin Artaud during the radio broadcast To Have Done with the Judgment of God on 28 November 1947.

Seized upon and re-interpreted philosophically by Deleuze and Guattari in the 70s and 80s, the concept of Body Without Organs shifted in subsequent decades to the world of the visual arts, particularly in the work of second-generation body artists. A case in point is the famous triad consisting of Orlan, Stelarc and Marcel Lì Antunez Roca who, in their performances, brought the hybrid onto the stage, the post-human body that does without its organs, substituting them with prosthetic technologies made of inorganic matter; a mutant body reconnected to practices of virtual and simulated reality, scientific experiments in robotics, biogenetics, etc. This move from the field of natural to cultural evolution has required new trans-disciplinary devices to visualise corporeal themes. These devices can still be seen today in the work of many artists whose poetics focuses on the post-human, that is on the strengthening of the human, or in other words staging the primordial obsession with the overcoming of death.

Seventy years have passed since the Artaudian claim concerning the Body Without Organs, a time-span that allows us to ascertain the longevity and the relevance of a concept that is still a metaphor for the body/a fragmented individual and social language, split and disconnected from any syntactical rules while, at the same time, not entirely liberated from this obsession.

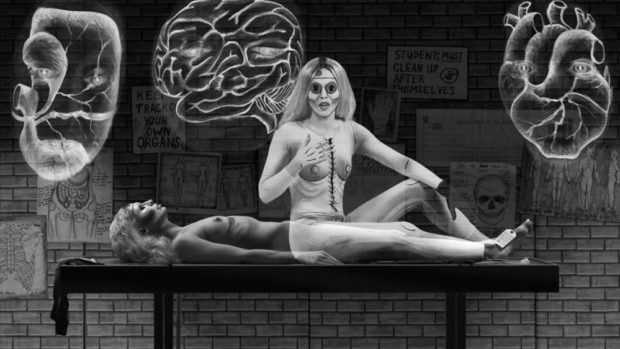

The video This Is Offal (2016) by Mary Reid Kelley is an example of how such questions are still deeply rooted in the contemporary artistic imaginary and is simultaneously witness to the emotional detachment originating from the very concept of the Body Without Organs, its existence as a ‘transitional’ entity and nature as defined and definite as death itself. The American artist, in fact, reinstates a grotesque vision, not without an element of black humour deriving from Artaud’s thought, through a “literal” citation of the body and its existence without organs post-death. The title is a play on the words offal/awful, which can both be traced in the theme around which the entire narrative of the film is centred: suicide and the awful, irrevocabile nature of such an act. On the subject of “offal” – to be precise the liver, heart, stomach, intestine and brain, to which a hand and a foot are added in the second part of the video – the artist devotes a unique dialogue, which takes place in a morgue, where the body of a young woman who committed suicide is prepared for autopsy. In this surreal and grotesque Theatre of Cruelty the various organs take on the features and expressions of a human face, in this case those of Mary Reid herself, accusing each other of being the trigger of the woman’s suicide, performing a dialogue that is both tragicomic and absurd.

Each of these organs, in the dock, accuses the others and defends its reasons with force, banalising and ridiculing the suicidal act which remains to this day “the only and truly serious philosophical problem”, as Albert Camus noted and whose writings are often cited by Mary Reid with reference to This Is Offal. In the essay The Myth of Sisyphus, however, as the artist herself underlines, Camus’ thought is lost in a simplified logic that is inclined to dismiss suicide as an attempted escape from reality. This line of thought, therefore, excludes the fact that suicide can be an act of free will without being necessarily liberating, as with the protagonist of the video.

Extreme vanitas is the matrix of pain which appears to have led the woman to put an end to her own existence. It is clear from the arguments put forward by her alter ego, materialising as a spectre which, at a certain point in the story, detaches itself from her body and takes centre stage: «Oh yes, my arms and legs will be remembered Now that I’ve joined the club of the dismembered (…) For me, there’ll be no sunset ride, My heaven is formaldehyde!».

Proud of having become an object of study and scientific observation and, thus, displaying its “offal”, the body becomes an open container, initiating its self-determination and infinite fields of possibilities (as evidenced by the scar/zip drawn at the centre of the woman’s bust and which she herself controls to allow various “animated” objects to exit). The “desiring-machine” – one of the definitions that Deleuze and Guattari gave the Body Without Organs – far from searching the satisfaction of a desire, even as a desire for death expressed in suicide, lives in its constant reproduction. This is a subversive, anarchic, dis-organic and dis-organised body insofar as its organs, deprived of their systemic functions, turn into prevaricating, slandering, judgmental and deceiving individuals. The same poetic dispute in rhyme that sees them protagonists makes extensive use of double entendres (a reference to the artist and critic Dennis Kardon who, in a recent article published in Art in America, speaks of “pun-ography”, where “pun” means a “play on words” in English), staging an endless betrayal of language. Freeing oneself from one’s own offal means, to be precise, liberating oneself from this type of judgement or, rather, “to be done with the judgment of God”, as the title of the aforementioned radio broadcast states, alluding to a possible emancipation of genetic and cultural norms imposed on each individual from birth.

It is interesting how, in representing the concept of Body Without Organs, Kelley uses film language that is intentionally obsolete. This language is, in reality, the outcome of a very sophisticated operation of digital editing – developed by her husband Patrick, who co-authored a large part of her work – and craft animations that are, in some respects, close to the “tricks” of the cinema d’antan. The use of highly contrasting black and white, the characters’s faces covered in heavy make-up to recreate extreme expressions and the use of painted backdrops taken from the theatre aim to resurrect an atmosphere suspended between hallucination and reality, worthy of the best The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the masterpiece of German expressionist cinema. However, on closer inspection, even the temporal inadequacy of the images, which is reconstructed through technical artefice that is far removed from the cold aesthetics of the body and technological devices distinctive of 90s cyber-culture, serves to underline the violent rendition of a scene in which the body, once again, is at the centre of a struggle taking place between two poles: on the one hand, the body’s resistance to the natural process of obsolescence and, hence, its obedience to the laws of umana vanitas is expressed; on the other hand, the fluidity that is connected to the body’s own desiring nature and free from any category of judgment is shown. The protagonist in This Is Offal, as a desiring-machine, silences her organs and pacifies their accusatory rage while, at the same time, representing voluptas in the sensuality of her features and gestures, making her desiring even in death and thus a victim of her own corporeal limits. From this cacophony of images, dialogues, techniques and visions, the absurd emerges as the natural dimension of an existence that, despite the progress of technical, scientific and philosophical theories and practices connected to the body, remains, from a Heiddegerian perspective, a “being for death”; irony emerges as an effective instrument for overcoming such unresolved meaninglessness.

This Is Offal is part of the solo exhibition of Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley, «We are Ghost», Tate Liverpool, until March 2018

images: (all) Mary Reid Kelley, This Is Offal, 2016, Single channel HD video with sound, made with Patrick Kelley, 12’51”. Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London. [film still]