The work of Shahzia Sikander comes to the MAXXI in Rome for the artist’s first Italian retrospective, “Ectasy as Sublime, Heart as Vector“, curated by Hou Hanru and Anne Paolopoli. A selection of works, over 30 works in various media and idioms (drawing, digital animations, installations), gives a remarkable outline of her artistic journey.

Having learned the art of miniatures at a very young age at the Lahore National College of Arts in Pakistan, and having studied the culture of Indo-Persian miniature painting and understood its worth at a time when the form was completely unconsidered and misunderstood, Sikander succeeded in making the technique her own, manipulating it to draw out all its poetry and narrative power, inserting and integrating it into new forms. “My first encounter with miniature challenged my personal convictions on aesthetics. Beginning with what I imagined miniature painting to be – a kitsch form of illustration for the benefit of tourists – I came to believe that classical paintings were dense, alive and heroic. It was the eroticism in the beauty of these paintings that transformed my point of view”.[1] This, and also her continual contact with different cultures, is the source of her artworks. With her perfect mastery of drawing and miniature art, Sikander has ventured into the contemporary where she founds potentials for refining and amplifying tradition.

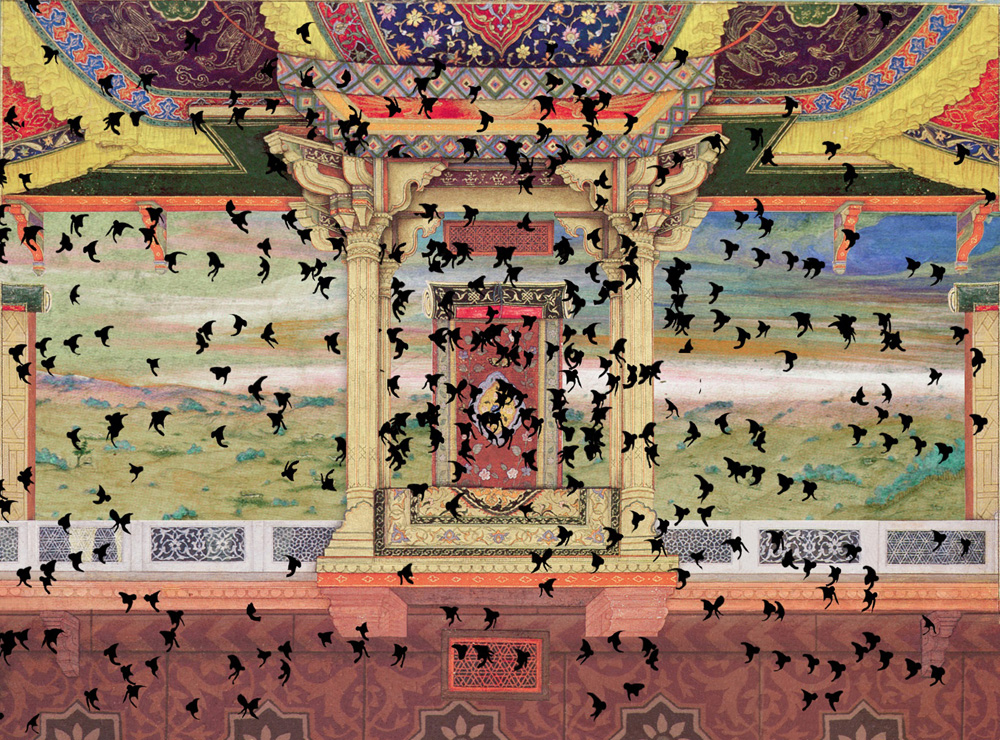

Curator Hou Hanru guides us through her work: “By superimposing real images and symbols taken from the cultures she encounters, the artist paints impure images of the world using purist techniques, drawings and watercolours animated in the usual way, and digital tools. These are splendid stories told by a maternal figure, similar to the one we knew in infancy. But this mother is nomadic and in difficulties, she is constantly wondering who she is and who she will become. And she shares with all of us her search for her roots and her desire to flee from her home to take in the world”.[2]

Content and technique journey in step with the search for constant expansion and experimentation, seeking the ideal space in which to “mount” tradition so that it becomes amplified to its fullest extent and consolidates the mystery of its narrative potential. It all hinges on the search for an interstitial space: “As with a Samuel Beckett play, in trying to capture the passage of time, the device for me is to invent the interstitial space. It is the gap, the silence, the break, the lacuna that acts as a foil to the narrative implicit in time”.[3]

Sikander’s stories swing between individual and universal experience, between technique and genre, and include poetry, opera and even contemporary hip hop. As she herself maintains: “The blurred borders between fiction and non-fiction, storytelling and historiography are all essential in the human search for truth”.[4]

In her research – sound and music play a central role, as in her early animations Nemesis (2003) and SpiNN (2003), Pursuit Curve (2004) and Dissonance to Detour (2005), featuring music by David Abir, or her later works, including the works exhibited: The Pendulum (2007 – 2009), Interstitial (2008) and Bending the Barrels (2009), with the insertion of choirs, text, songs and poetry.

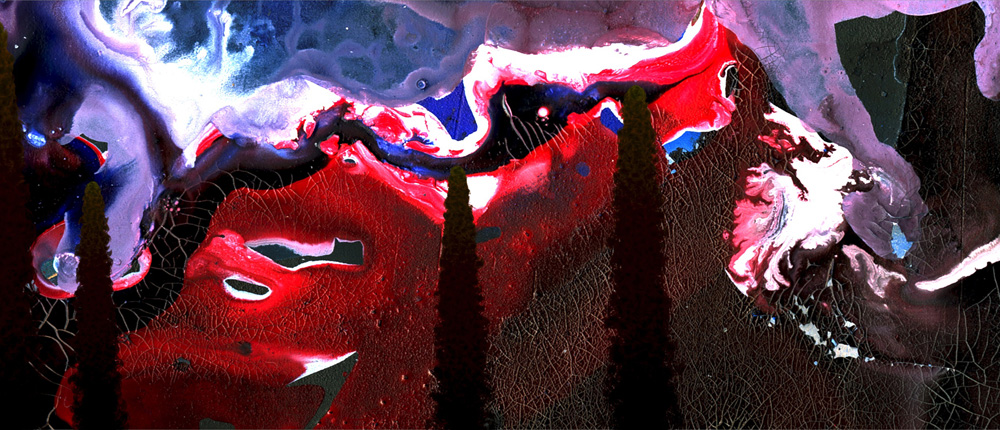

The soundtrack is also central in Parallax (2013)[5], a large-scale installation featured in the exhibition, a celebration of the power of visual-sign-sound narrative. Created by Du Yun, with whom Sikander has collaborated since 2010, it includes instrumental music and scripts recited as poetry. Here the silhouettes of the hair of Gopika (devotees of Krishna), present in many of her works, raise the curtain on the video and the exhibition: hundreds of animated drawings, metaphors, fluctuate on the screen and transform themselves to recount issues relating to conflict and control: British colonialism, the discovery of oil in the 1960s, the hegemony of the United States. Everything flows in a beguiling and poetic dimension.

For Sikander, modern technology has proved to be a medium for reinventing and enhancing an ancient technique. Craftsmanship, awareness of the mechanisms of perception combined with knowledge of materials is inherent in the magic of all her works, beginning with the pieces created in the early 90s using paper prepared with the wasli method of overlapping several sheets. Scroll, her thesis piece for the Lahore National College of Arts (1989-90), used this technique and gave rise to her idea of space “not only in the sense of scale, but in terms of possibility”, as she herself states, interviewed by Manuela de Leonardis in a wonderful article published in the pages of Pagina 99.[6]

At the MAXXI, this type of work is represented by her more recent piece Echo (2010), designed as a site-specific work and, like the others, acting as an image-creating device in the layering of images and thus of the narrative dimension. A shift in scale in terms of possibility also lies at the heart of her Meta Book, produced in 2006 in conjunction with Fabric Workshop and the Museum of Philadelphia. Here the space of the miniature becomes enormous, ferried towards a sculptural dimension.

Even the exhibition catalogue, some lines of which we have quoted, is an exquisite object, refined in form and content, a taster for the work of an artist who expresses herself through her art “in a constant negotiation with displacement and adjustment. And the artist always ends up going beyond, further away”[7].

[1] S. Sikander interview by Alvaro Rodrìguez in Ecstasy as Sublime, Heart as Vector, Bruno publisher, 2016, p.96.

[2] H. Hanrou in Ibid, p. 54

[3] S. Sikander in an interview with art historian Fereshteh Daftari, quoted in the catalogue text by Claire Brandon, Ibid, p. 70.

[4] S. Sikander interview by Alvaro Rodrìguez, Ibid, p. 92.

[5] Parallax is a 3-channel video animation 20 metres in lenght, created for the Sharjah Biennial (United Arab Emirates) and adapted to the curved space of the MAXXI Museum’s venue where it is hosted.

[6] Manuela de Leonardis, Il viaggio di Sikander tra miniature e video, “Pagina 99”, Saturday 18 June, 2016.

[7] Hou Hanrou, in Ibid, p. 50.