Semiconductor is a duo of young British artists, Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt, engaged in a multifaceted exploration whose starting point is the collection and processing of scientific data (regarding for example earthquakes, volcanic activity and climate data) and their transformation into visual and sound installations. The duo’s interest lies wholly in examining the various ways in which natural phenomena are filtered through the lens of science and technology. Earthworks, their most recent production, was protagonist of the Sónar Festival (16-18 June), as the 2016 project sponsored by the SonarPLANTA project, a collaboration between Sónar and the Sorigué Foundation aimed at encouraging research into creative languages involving art, science and technology. By translating scientific data into a spectacular installation, Earthworks visualises the formation of the Earth and its changes over time, increasingly determined by human and technological intervention, to the extent that a new geological age has been recognized in the term of Anthropocene. We asked them some questions about their latest work and their creative approach to art and science.

Arshake: How did the idea of Earthworks come about?

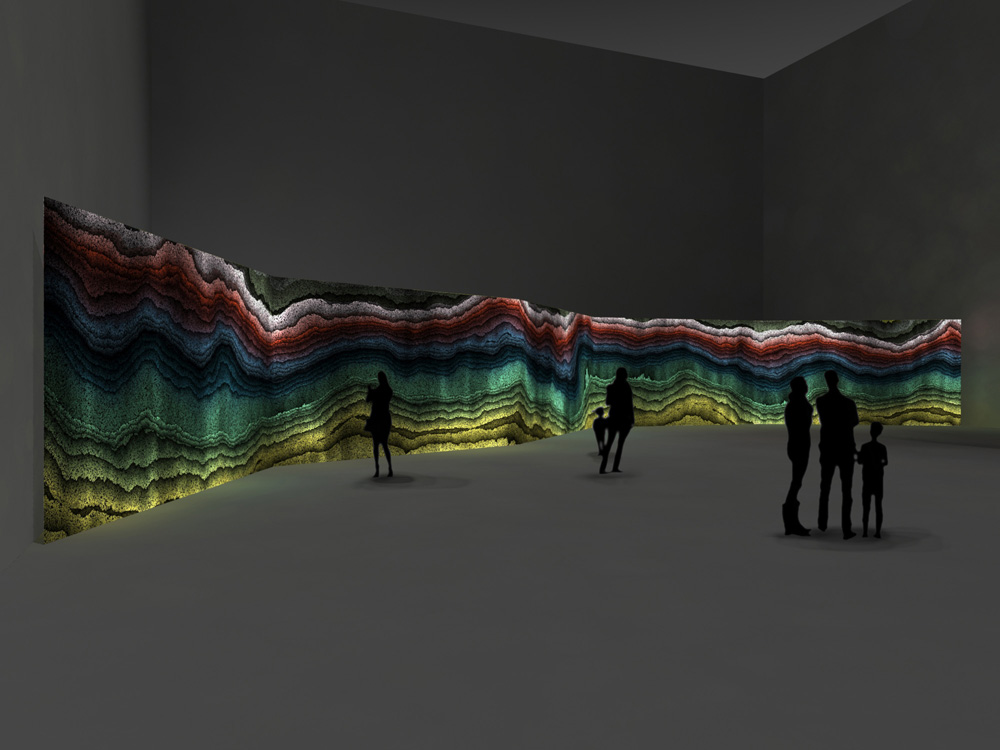

We were inspired by how you could read the layers of the landscape in the quarry face at Planta and looked into the tools that scientists develop to try and create an understanding of it. We came to Analogue Modelling through our research, and the lab at the University of Barcelona are doing some really amazing work which replicates landscape formation through these colourful layers of sand and application of pressure. The results are quite stunning. We have a history of animating landscapes with data that is captured from it and in this instance it made sense to acquire seismic data and reanimate the landscapes to suggest a kind of landscape formation time-lapse.

You usually work with data and in close contact with scientists. For Earthworks you collected seismic data from the IRIS (Incorporated Research Institution for Seismology) public archive and from the surroundings of PLANTA–the quarry of Fundació Sorigué near Balaguer (Lleida)– with assistance from experts in geotechnology from the School of Earth Sciences of the University of Barcelona.What does collecting data represent in your creative process?

The collection of data has many roles in our work, whether its data as a sequence of numbers or visual data captured through imaging technology. Man’s signature is quite dominant in the collection of data of the physical world especially phenomena that occur beyond the limits of our perceptions. Decisions made about what to capture and how to capture it come with limitations in terms of time frames and technologies and we’re interested in how this process introduces man’s signature into the observation of the natural world. Are we experiencing nature or a mediated version of it?

We treat the data in our work as a manifestation of a physical material but one that exists beyond our perceptive or physical limits. So here, with the seismic data the scientific instruments are recording the vibrations from the Earth, these vibrations occur at frequencies which are beyond our audible range and perhaps over a time-span which we cannot sense the movement. In this sense the data represents a natural order that we can sculpt with, reintroducing movement and sound and a physical sensation to our seemingly static world.

![]()

How do you think the language of science mediates nature? And how do you apply the scientific method to your work?

A solar physicist once said to us ‘science is a human invention it’s nature that’s real’. This lead us on an interesting path of discovery, realising it was ok to query science, that it’s not providing answers but asking questions. Through the process of scientific investigation man develops technologies which interpret the natural world; these can often introduce elements whether it’s intentionally as part of the scientific language or artifacts introduced in the capturing process. As a layman it can be difficult for us to distinguish what is part of nature and was has been introduced blurring the lines between what is nature and what is mediated. We like to play with these boundaries on the one hand to question science as a process and then also to use these technological signatures to remind us of man as an observer of the natural world.

What does Earthworks represent in the path of your research?

It’s great to have the opportunity to make a work on such a large scale, so that it becomes comparable to being in the landscape. Our works often require to be seen on quite specific scales, whether it’s more intimate pieces like Magnetic Movie or larger scale works like Black Rain which takes on the scale of a waterfall. Earthworks has become truly immersive in scale.

How do you usually structure your creative process as a duo?

The structure of our creative process is different depending on how we are making a work. In this instance we spent time visiting locations and researching then developed the idea. We worked with a programmer to develop a software tool that we could animate with; this was the most time intensive part as you’re doing everything from scratch and have to make decisions about micro-details. We like to lead the software as well, so we’re constantly pushing it as far as we can. We’ve worked together for twenty years so it’s difficult to find the boundary where ones role stops and another one starts.

What stage do you prefer, creatively speaking, while putting together a project?

The best bit is always the fantasising about what a work might be, playing with ideas, taking them as far as possible and thinking what if there were no constraints. There’s a certain headspace you need to get into where the ideas start flowing and nothing else matters. You both have previously worked as residents in scientific laboratories such as CERN. What extent you were able to establish a dialogue with scientists? How was your presence perceived by them? How has this experience influenced your current work?

We always have to work hard to be accepted into the science laboratories we’ve done residencies in. There seems to be a familiar pattern where initially scientists are understandably suspicious of us, then as we spend time with them probing more about their science and relay a genuine interest we seem to build up a rapport and a trust. This certainly happened at CERN and is continuing to happen as we continue the relationships we formed. We spent a lot of time talking to theoretical physicists, I would say interviewed but we weren’t really controlling the direction of conversation! We are about to start production with our CERN work.

![]()

Your works visualize nature. Did the collected data reveal something new to your knowledge about the era we live in, recently defined as Anthropocene? Do you believe in the collaboration of art and science as a potential tool for improvement? And if so, what sort of improvement?

In Earthworks it’s interesting the physical effect the different seismic data has on both the animation and your experience of it. There are four different sources of seismic data; earthquake, glacial, volcanic and urban. Each one is quite distinct and the urban data which represents the Anthropocene is much noisier, both visually and sonically which is very interesting.We have seen how collaborations between art in science in our own work have improved the communication of science. Various artworks of ours have been adopted within the realms of scientific communication and we continue to see how they continue to influence. As a result of the internet and science papers and stories being so much more widely available these days, the science community is much more aware about public awareness and how important it is to engage visually. Of course this is not our intention as artists when making the work but it is a very positive side effect in these sort of relationships.

Earthworks by Semiconductor was depicted at Sónar Festival in Barcellona (June 16-18) as the annual project sponsored by the SonarPLANTA project, a collaboration between Sónar and the Sorigué Foundation. Sónar has just closed its doors in its native city of Barcellona, buti t continues in an increasing number of event around the world that from this year also count Sónar Hong Kong (1 of April, 2017), and Sónar Istanbul (24 and 25 of March 2017)

Semiconductor (Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt) has received numerous awards, including the Samsung Art+ Prize for New Media, the Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, the NASA Space Sciences Fellowship, and the Collide@CERN Ars Electronica Award. For the artists this has meant extending their research by spending several months in residence at the respective laboratories: the NASA Space Sciences laboratory, the Smithsonian Mineral Sciences Laboratory, the Galapagos Charles Darwin Research Centre, CERN in Geneva and the Ars Electronica Futurelab in Linz, the Ars Electronica laboratory. Their work has been presented at various prestigious institutions such as the House of Electronic Arts (Basel), FACT (Liverpool), the ArtScience Museum (Singapore), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Royal Academy of Arts (London), the Sundance Film Festival (Utah) and the International Film Festival (Rotterdam). Their works Magnetic Movie and Brilliant Noise are part of the permanent collections of the Hirshhorn Museum (Washington DC) and the Pompidou Centre (Paris).

images (cover 1) Semiconductor, Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt (2 -3) Sónar Planta, dettaglio del sismografo (4) Semiconductor, Earthworks, rendering (5) Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt a UB (6) Earthworks, video at Sónar Festival in Barcellona (16-18 June, 2016)