The Castle of Rivoli is hosting a project by Hito Steyerl in the Manica Lunga, a seventeenth century building that once connected the central part of the castle with the Duke’s former picture gallery.

The City of Broken Windows, the title of the installation, is a continuation of the artist’s comprehensive intellectual research, always engaged in exploring the role of media, technology and the circulation of images in the age of globalisation. Her analytical vision is materialized in a linguistic grammar shaped by different genres: from cinema to documentaries, from oral performance (Steyerl is known for her performative lectures) to the most classic forms of the written word which, in her hands, are no longer so “classic”. What is perceived as an objective reality is stripped of its media gloss.

Turning to the installation itself, Broken Windows is rooted in Steyerl’s research on the AI industry (Artificial Intelligence) and surveillance technology. The whole installation is situated inside Steyerl’s dialectic game which, in this case, ranges from high-tech (and its fallibility) to the urban scene, including the whole framework of capitalism, which is defined by the manipulation of technologies through the images that these produce.

Along the entire Manica Lunga corridor, several loudspeakers broadcast the noise of broken glass re-elaborated using Artificial Intelligence: «a discordant symphony consisting of glass shards mixed with the sound of bells[1]».

Tow videos installed on easels face each other, each one at one end of the long corridor: Broken Windows with its grey monochrome background and Unbroken Windows, with a smashed window which appears to have been hit from the outside. In the first film-documentary [Broken Windows], the testers hired to break the windows voice their opinions while, in the second [Unbroken Windows], the story of Chris Toepfer is narrated, a man involved in redeveloping entire neighbourhoods by painting abandoned homes and repairing broken windows using decorative board–up.[2]

The dialectic of the image is here broken into many other dialectic levels. In this piece, these levels intersect between the threads of an apparent technological perfection and «idealised hope and trust in technology and automated learning[2]»; that same perfection man can reach by himself, using a paintbrush, in an imaginary simulation that actually recreates reality and demonstrates the same efficiency and power as technology. The world is now trapped and embedded in this dialectic.

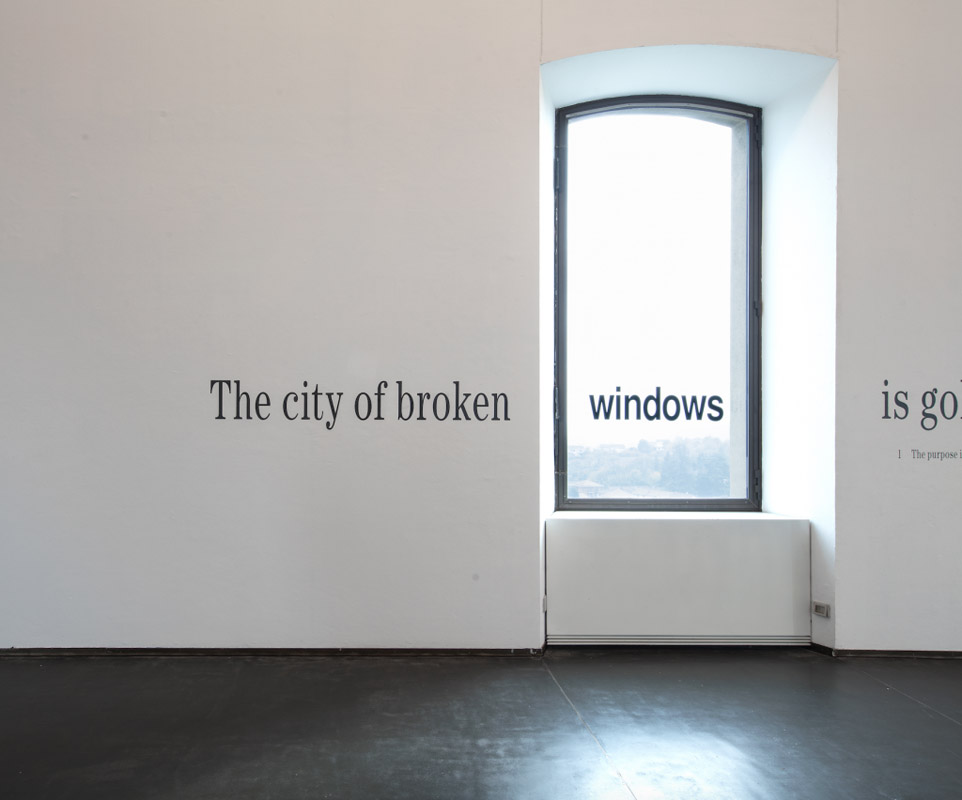

The contents of the videos facing each other in the Manica become tangible and extend through space thanks to the vinyl text that runs in a single line interspersed with notes, along the entire length of the wall, forming a circular itinerary. The right side consists of statements made by the testers mixed with utterances with no grammatical sense which have been badly developed by the AI together with extracts from Bastiat’s The Tale of a Broken Window, which appear as footnotes. Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) was an economist who focused his attention on the consequences of invisible, rather than visible aspects of the economy. The return, on the other hand, consists of the same alternation of written text and notes, the words of Unbroken Windows.

Text has always been Steyerl’s preferred medium and, through a series of essays, she has offered new perspectives and terminology to be found in significant texts.[4] In the catalogue, there is an essay by Griselda Pollock specifically dedicated to Steyerl’s writing, which Pollock defines as a «work-word, like that in an artwork» in an attempt to associate the ways in which the artwork is connected to the process of constructing meaning. More importantly «the texts elicit meaning rather than produce it. Reading Hito Steyerl’s writing makes one highly attuned to the weight of each word because the flow of her words is already a place where processes and effects, elusive but nevertheless real, are taking place, which the words are trying to somehow express [5]». Now, for the first time, this vision actually enters the installation in an incisive way. Not only do the writings become extensions of the video content, but they can be read only when visitors move, transforming the installation into an «embodied experience», as defined by Bakargiev, in «a celebration of thinking, feeling, listening, reading and walking bodies in the museum space[6]».

The installation is minimalist and, at the same time, powerful. The reduced effect of the spectacular is transformed into a powerful device. The entire installation is based on the power that fragility has to remain in equilibrium. The catalogue that accompanies the exhibition complements the installation, a bridge between this recent work and the constellation of Steyerl’s thinking; a continuity and link between past and present. The various critical analyses in the essays produced for this exhibition, alternating between Steyerl’s artistic and written production, together with a very detailed and polished chronology and anthology of her work, are collected in an extremely carefully curated volume, from content to graphic.

[notes]

[1] M. Vecellio, L’immagine infranta in: C. Christov-Bakargiev, M. Vecellio (edito da), “Hito Steyerl. The City of Broken Windows”, cat. of show, Skira, Milan 2018, p. 21

[2] These are sounds extrapolated from the testing systems of Audio Analytics, a British company that developed patented sound recognition software called ai3, supplying technology that is able to recognise context through sound input.

[3] C. Christov-Bakargiev, Dimenticano la violenza dei loro gesti. Finestre, schermi e atti pittorici in un tempo inquieto in C. Christov-Bakargiev, M. Vecellio (edited by), “Hito Steyerl. The City of Broken Windows”, cat. of show, Skira, Milan 2018, p. 41 (translated from the Italian version)

[4] Among her publications are to be mentioned: In Defence of the Poor Image in the online e-flux magazine of 2009 (later published in the anthology The Wretched of the Screen, e-flux e Sternberg Press, 2012) and the more recent Duty Free Art. Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War (Verso Press, London and New York, 2017).

[5] G. Pollock, Vedere non significa sapere. Dire ci permette di vedere. Sulle opere-parole di Hito Steyerl in C. Christov-Bakargiev, M. Vecellio (edited by), “Hito Steyerl. The City of Broken Windows”, cat. of show, Skira, Milan 2018, p. 41 (translated from the Italian version, p.46

[6] C. Christov-Bakargiev, Ibidem in “Ibidem”, Skira, Milano 2019, p. 45

Hito Steyerl. The City of Broken Windows / La città delle finestre rotte, curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev and Marianna Vecellio

Castello di Rivoli (Turin), 10.11 – 18.1.2018 – 01.09.2019

images: (all) Hito Steyerl. The City of Broken Windows, Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rivoli – Turin, 2018. Photo: Antonio Maniscalco