The American Academy in Rome will not forego the Winter Open Studios during the pandemic. We met with Tina Tallon and James Beacham, who with their interactive installation Subsumption, No. 1 combine the sounds of an ancient Roman aqueduct with data from Cern in Geneva.

In these winter months, with Covid still very much present, being able to organise cultural events open to the public is not something to be taken for granted. At the American Academy in Rome, they wanted to honour the recurring Winter Open Studios event by introducing the scholarship holders who arrived in September, with more coming soon. A choice with which the institute’s management and the new interim Andrew Heiskell Arts Director Lindsay Harris wanted to give a sense of normality and ‘openness’ to the city (See here the files of participating scholarship holders.

We spoke with Tina Tallon – artist, musician, lecturer, entrepreneur, with an engineering background – and physicist and filmmaker James Beacham from Cern in Geneva – interested in the exploration of sound and harmony – about the installation Subsumption, No. 1, the first step of a long-term work that premièred in Rome. Having met on the internet a few years ago, the pair have collaborated on various projects about sound data and our perception of and interaction with it.

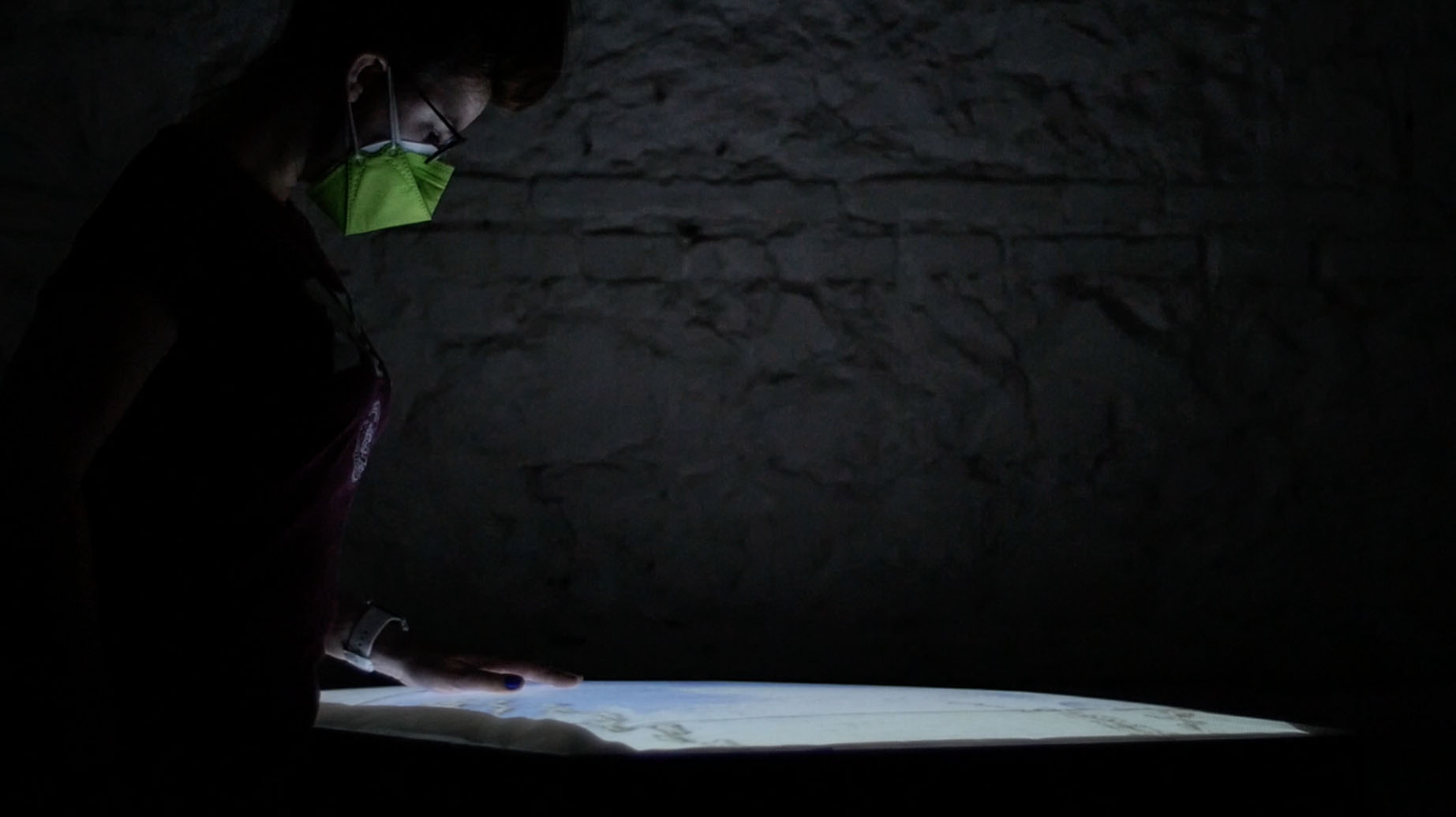

The work can be seen in the building’s cryptoporticus, an underground space that lends itself well to multimedia works. Hidden from the visitor’s view, on the lower level, a microphone records and transmits to the upper level a base frequency from the Roman aqueduct on which the academy was partially built. Water is the link with the city of Rome, which has made it an artistic material since ancient times, its murmur characterises streets and squares, as Madame de Staël wrote in front of the Trevi Fountain. And, let’s not forget, just a few metres from the Academy stands the Fontanone del Gianicolo, with whose grandeur Sorrentino began The Great Beauty. The aqueduct structure is no longer in use but Tallon was able to include it in the project thanks to a special permit.

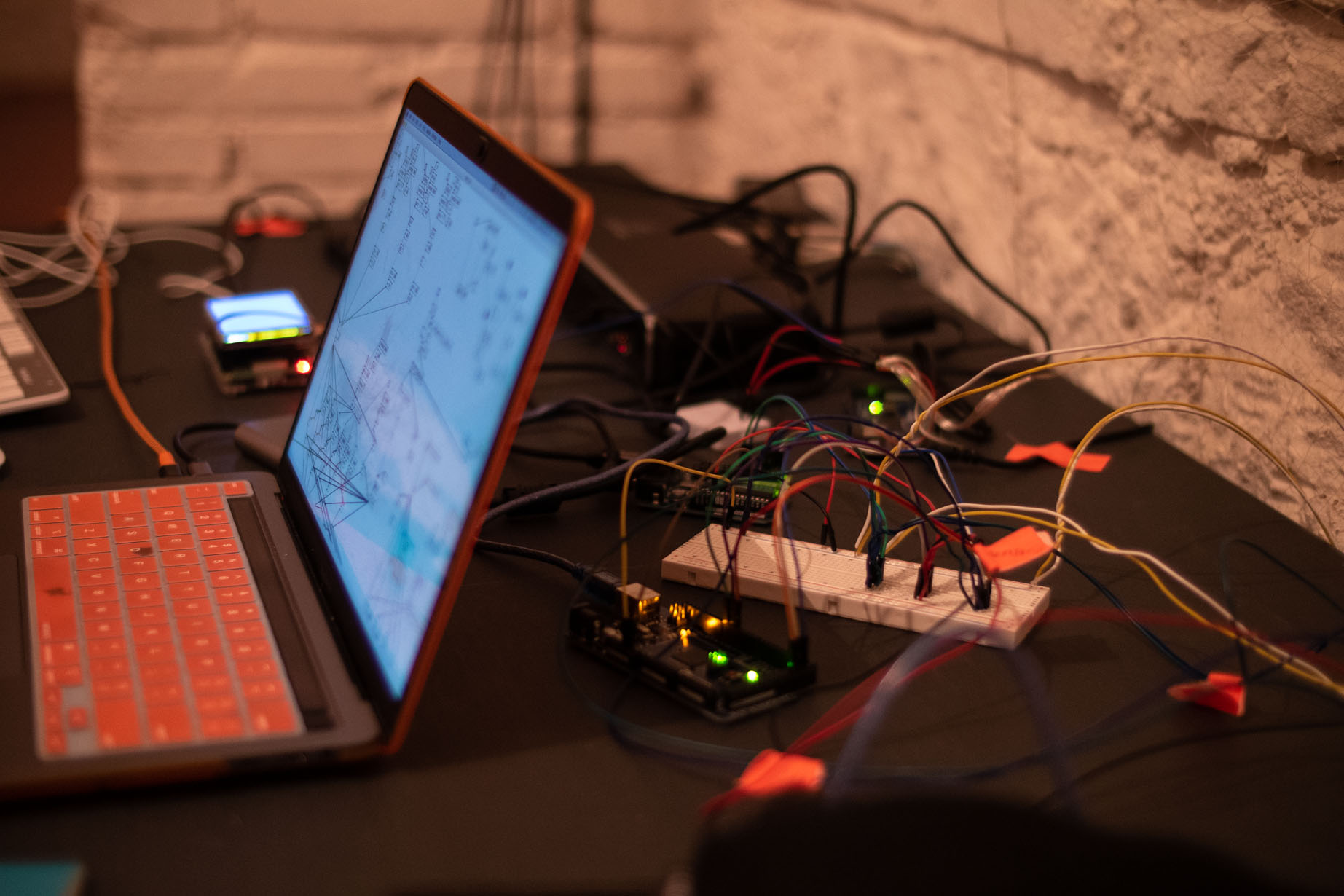

Upon entering the cryptoporticus, the darkness of one of the arms is illuminated in a constellation of LEDs that sense the movement of people walking through it. At the centre of the passageway, a screen installed on a black cube projects towards the ceiling; when touched, images and videos taken by Beacham on the premises of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at Cern in Geneva, the largest particle accelerator in existence to date (it is 27 km long) in which the state of matter immediately after the big bang is recreated.

The site-specific installation is responsive to the behaviour of the visitors, who gradually enter into the structure of the work. One is attracted by the passage through the semi-darkness, the behaviour of the lights, the bright screen, the sounds and images coming from afar. What are the sounds that overlap in real time (the frequency of the aqueduct, the film)? How are they perceived? Does the sound follow you or do you follow the sound? One of the focal points of the two artists’ research is to use unconventional stimuli to investigate our behaviour, which is not always conscious, in order to bring to light the structures of our being in the physical world, which give rise to our experiences of space and time. And analyse the resulting data on interaction with the work, which will be received differently depending on the context.

Subsumption, No. 1 is in fact also a research work on data management bias. “Here at Cern,” says James, “thanks to the collider, we have at our disposal perhaps the largest data set in the history of mankind – a huge amount of petabytes of raw data, which we must learn to read. How should we collect it, structure it, decide what to keep and what not to? Both Tina and I are interested in a more evolved approach to intersonification, that idea where you take a set of data, like the noise of a telescope, that you can’t hear even though it exists, and you make it coexist with something audible and human. Often those who work on data sonification produce very interesting – even beautiful – work, but there is still a selection, a choice that can amplify the distortions of those who read them. We will work on this more in the future”.

“A common example,” Tina points out, “is when you write a composition for piano, based on data perhaps from a telescope, which you have to feed into the rigid structure of the keyboard and which doesn’t allow you to show the essential nature of that data. As an artist I try to approach data without the lens that we usually use, asking myself what is actually there. If you look honestly at what it says, you can find new things there.”

Tina Tallon is featured in the Academy’s programme as a fellow in music composition. As we say goodbye, we talk about the problem of classifications and categories, which artists like her find hard to identify with. On her website, she calls herself a creative technologist and a temporal media artist, a definition she arrived at by trying to combine scientific studies and artistic practice. “The term ‘composer’ did not seem to fit. I am personally interested in what we perceive as a signal and what as noise, what it tells us about our history, how we communicate. In my job I create software, work in teams with many people, I write, I do research and I am a historian. It is not traditionally what a composer does, at least according to our understanding of the term. The definition I have created is less restricted and allows me to experiment more freely.”

images (all): Tina Tallon and James Beacham, «Subsumption, No. 1», 2021, ph: Tina Tallon