Scrivere non è descrivere [Writing is not describing] is a solo exhibition by Tomaso Binga (aka Bianca Pucciarelli Menna, Salerno, 1931) at Galleria Tiziana di Caro in Naples, which focuses on a significant group of the artist’s works from the early seventies: the Scrittura vivente series, Dattilocodice and the entire series of 52 typewritten letters that are part of the performance Ti scrivo solo di domenica. These works serve as an introduction to the artist’s subsequent inventive research, which found its continuation in a cross-breeding of painting, digital art, photography and performance, all characterised by the central role of language, its new values as an icon, its resonance and its embodiment in the body of the artist herself. Letters and words (including the words of her poems) are granted their own life, and arrive in the space through the body of the artist, who delivers them in a performative act.

For some time I have had in my possession a small book which impressed me greatly and which I have been waiting for the chance to review. The title is Tomaso Binga. Scritture viventi, edited by Antonello Tolve and Stefania Zuliani and published by Plectica.

Now, the exhibition at Galleria Tiziana di Caro gives me the opportunity not so much to review it as to indirectly involve it, with its numerous voices of critics and professionals who have followed Tomaso Binga’s career over the years and experienced her work first hand. These will be my companions as we go throughout the exhibited works, while at the same time giving an idea of this choral introduction to the work of Tomaso Binga, an artist who “has made the transformation of the canon the mainspring of her undisciplined research, restless yet always recognisable in its outspokenness, its determination to construct the new, its conviction that experimentation is not merely a possibility but the very nature of artistic endeavour”[1].

Indeed, besides previously unpublished essays, the book contains a dense anthology of criticism, including texts which have accompanied some of Binga’s most important shows from the seventies to the present day[2]. I pass the microphone to them, in an operation which obviously implies a choice, in my case not conforming to the sequential order of the texts, a selection that can be overturned and reassembled differently each time by visitors of the exhibition who carry the book with them, either physically or in their heads.

The book opens with the words of Tomaso Binga belonging to the the autobiographical note she read when accepting an honorary degree from the Academy of Fine Arts at Macerata in 2013, which immediately shows her ironic tone and musicality:

“I, Tomaso Binga, was born in Salerno in the last century, but I live and work in Rome.

Drawn to literature from an early age (I started writing poetry at 10), my career in art began in the early sixties, but I didn’t stand up and be counted until 1971, in the midst of the feminist fervour, when, ironic and provocative, I took a masculine name for my art. Since then my work has developed – always with great consistency – in the fields of Verbal-Visual Writing and Sound-Performance Poetry.[3]”

“Tomaso Binga works between poetry and painting, at the edges of words and the edges of painting” wrote Trimarco in “Il Mattino“ in 1992 – edges and limits that she interrogates and coerces in order to redefine the terrain of these ancient disciplines, techniques which follow each other and intertwine, only to separate again afterwards[4]. “my extreme experiment/is to shoot down commentary/overturn conventions, risk utopias/shadow sounds and movements/weave together anomalies[5]”. These are the lines of Binga’s poetry chosen by Stefania Zuliani as a “soundtrack” to this existence of hers on the edges of things and of life, “in the certainty that it’s in mixture and hybrid, in impurity, that all real possibilities for art and for life are to be found”.[6]

But let’s take a closer look at the works on display.

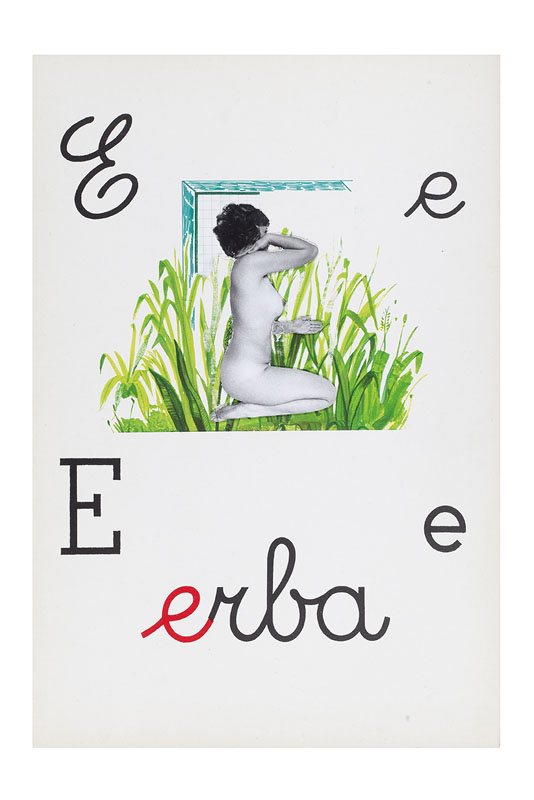

Binga’s Scrittura vivente series (1976), in which the outline of her naked body mimics the letters of the alphabet, defines her practice of writing, which “…transgresses the horizontal nature of the sheet of paper to gain embodiment, to become the body” [7]

Antonello Tolve begins his essay by recalling Walter Benjamin’s Alphabets of a hundred years ago (1928), whose interpretation of letters as a doorway opening onto the world of childhood gives it a balletic dimension very close to Binga. “For Tomaso Binga”, continues Tolve in his critique of the works, “writing is a useful structure for producing new meanings, works in which text – textum, in its original sense – is a fabric, a dense mesh that orders the discourse so as to enrich itself in space, time and material, to generate a poetry in sound and vision which feels the urgent need to become a lyric performance, a carnal song”. [8]

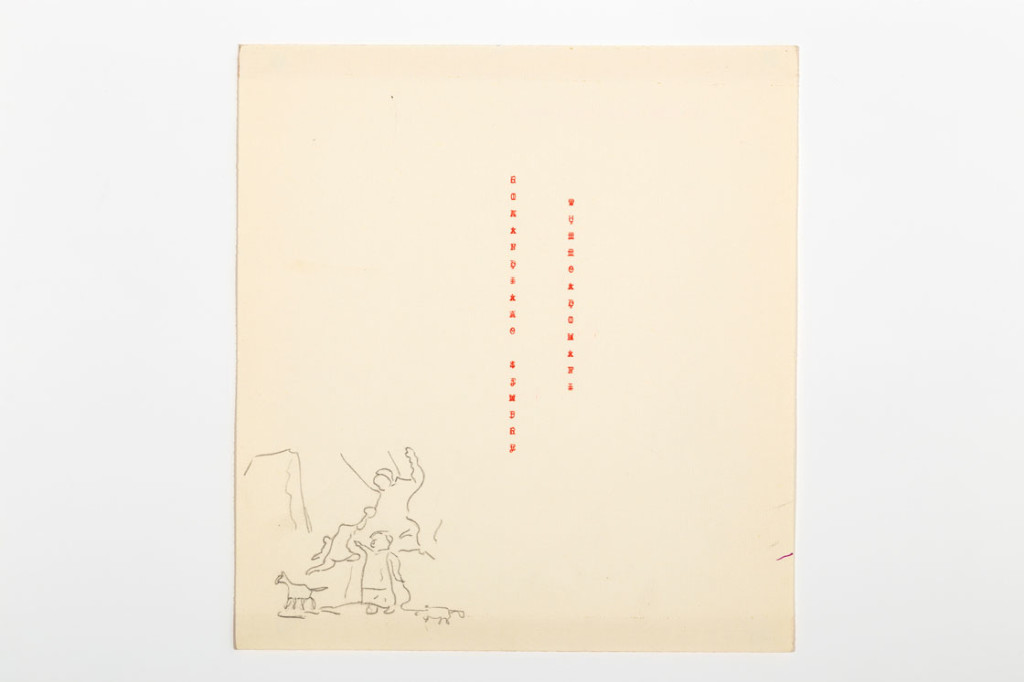

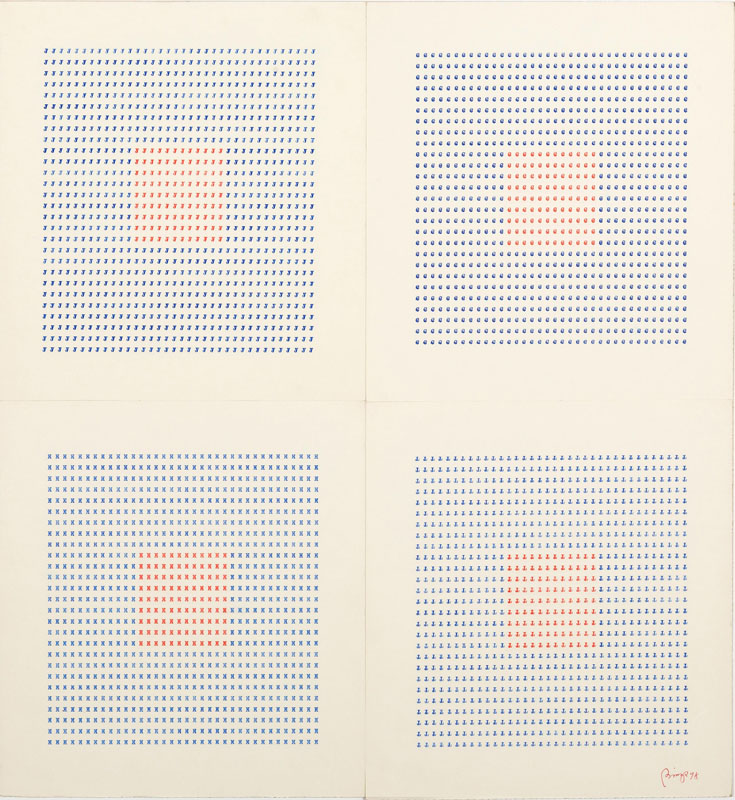

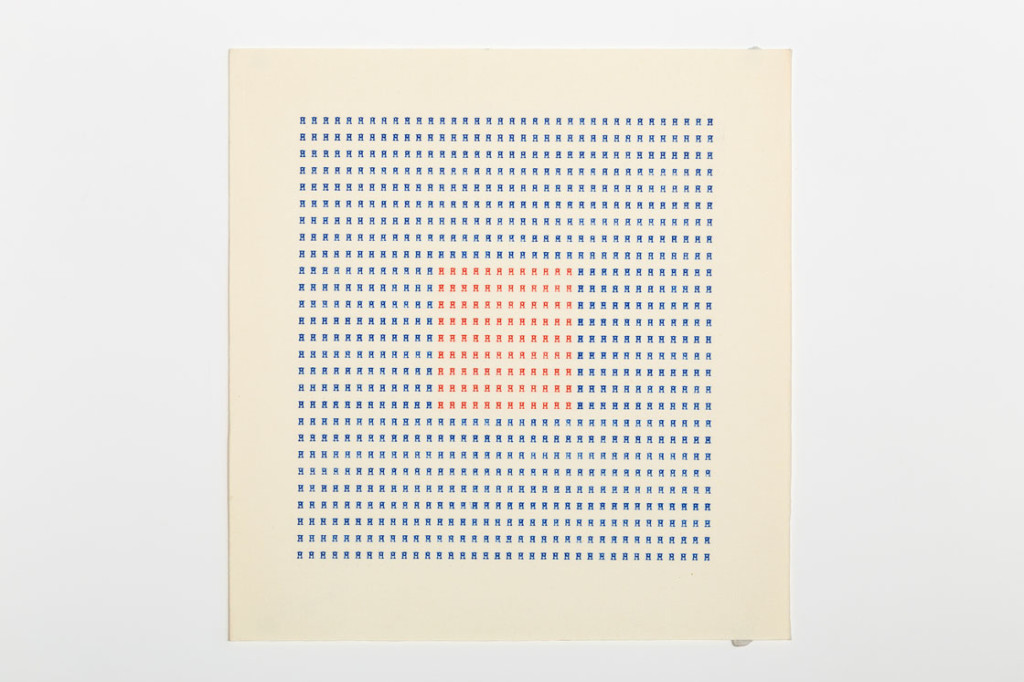

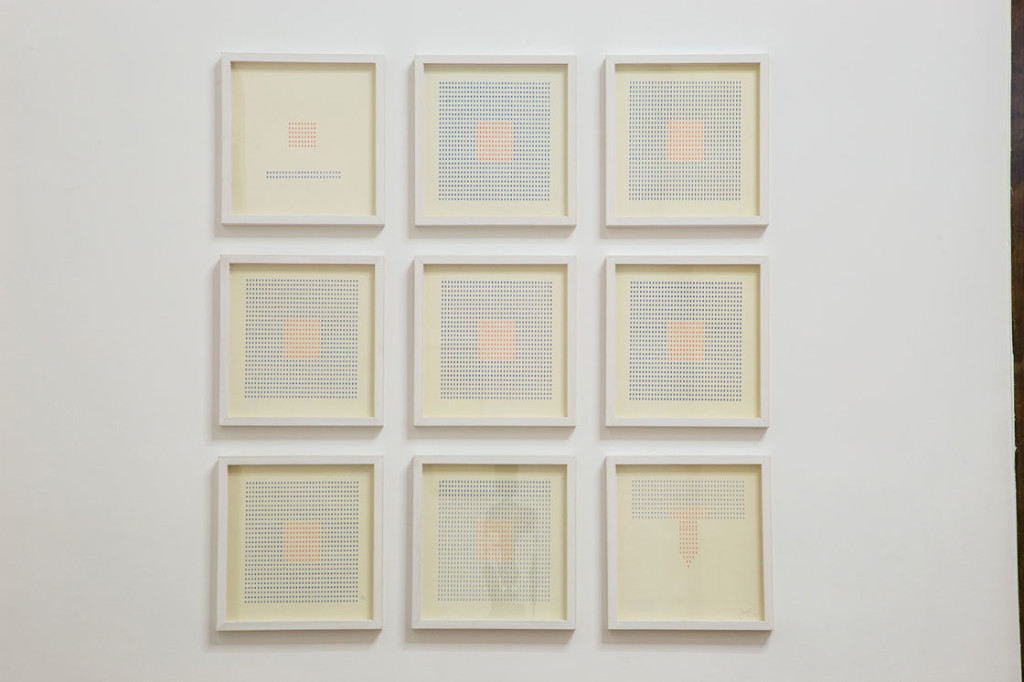

We come to 1978, when Dattilocodice is proposed as a new experience in writing. The artist presents it at the Venice Biennale as part of the “Materializzazione del Linguaggio” exhibition. In this new type of writing, a kind of “poetic-concrete syncretism”, as Dorfles describes it in 1981, the typewriter’s graphemes overlap, “with a result that is more graphics than writing”[9]

“Body and writing always coincide”, writes Moschini in the catalogue for a show in 1987, “even when they appear distant, as for example in typescript, we find them united through the words of a poem (“with a single finger/I strike a key/the same key I strike/and strike again/up to nine/new images…)”.[10]

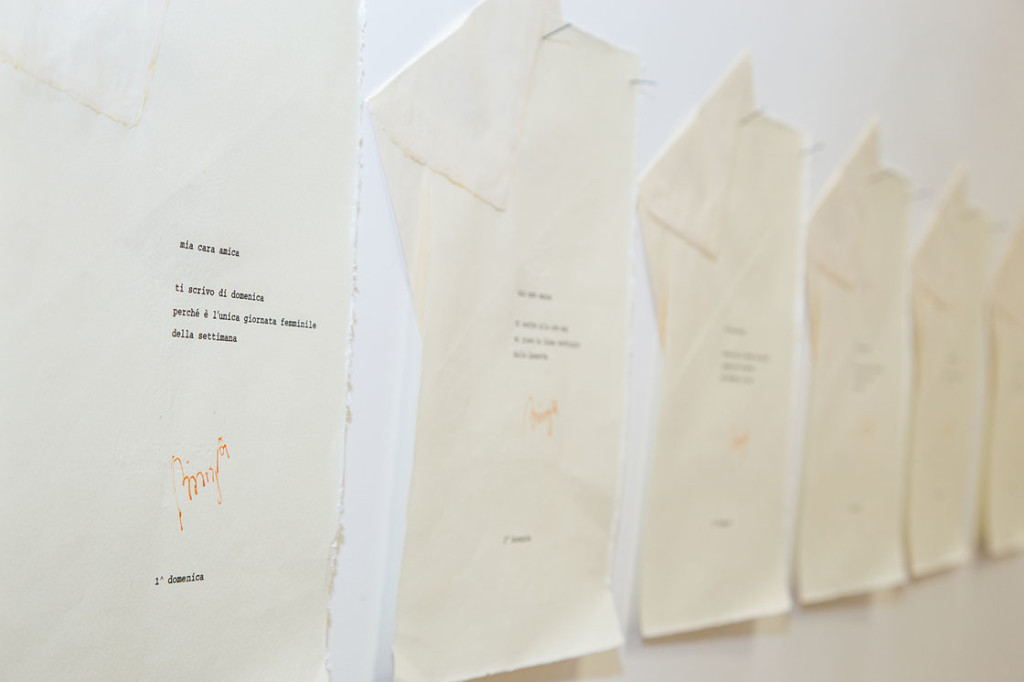

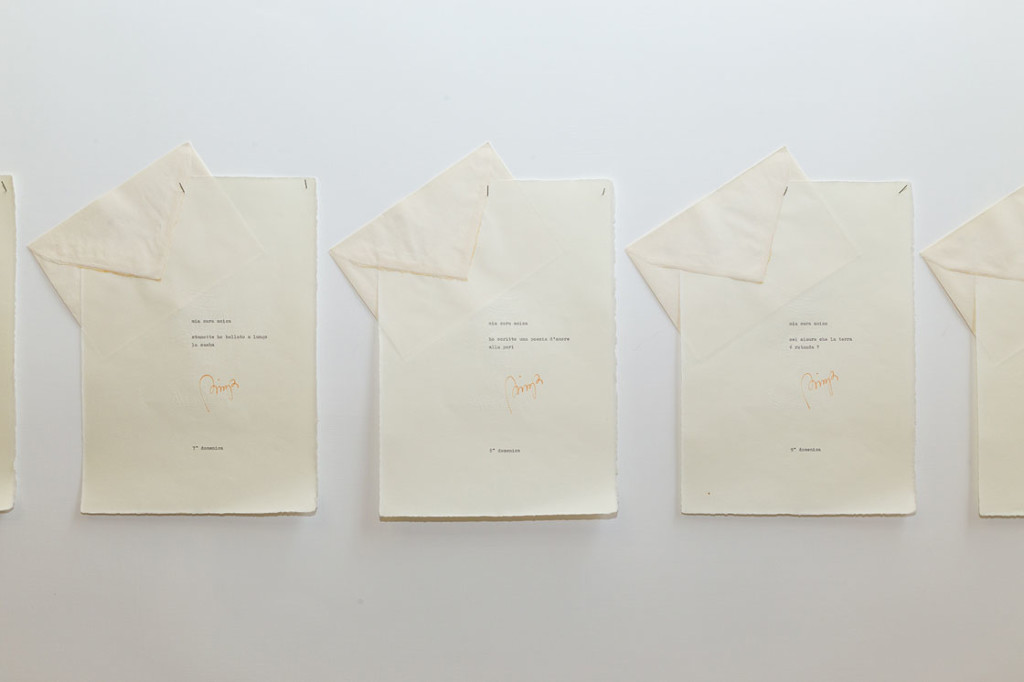

In Ti scrivo solo di domenica, this embodiment of the word rests upon the quality of the sound made by the artist as she pronounces it. The words are what Binga reads aloud in a performance, words that belong to the letters she wrote to a friend (her alter ego) every Sunday for a whole year.

“I have re-evaluated the rhythmic and tonal properties of the word in order to bring warmth and colour to the harmonies of the verse, where signifier and signified intertwine and alternate in a continual and controlled play of distortions” (T. Binga). The exhibition contains the entire series of typewritten scripts.

Thus three groups of works, viewed together and in rhythm with the space, give an all-encompassing profile of a multifaceted artist, and distinguish her also in her capacity as director of the historic Lavatoio Contumaciale art centre in Rome, run since 1971 as an interdisciplinary meeting space, “almost covering, in a sort of ideal game of combinations, the terrain of experimental synthesis between art forms (…)” [11]

Tomaso Binga, Scrivere non è descrivere, Galleria Tiziana Di Caro, Naples, Italy, 24.09 – 14.11.2015

e

A. Tolve, S. Zuliani (a cura di), Tomaso Binga, Scritture Viventi, Plectica, Salerno 2014

[1] A. Tolve e S. Zuliani (a cura di), Scritture Viventi, Plectica, 2014, (from the back cover).

[2] with contributions by Migliorini, Argan, Cortenova, Agnetti, Loda, Mussa, Bentivoglio, Dorfles, Maurizi, Moschini, Balmas, Milanese, Trimarco, Muzzioli).

[3] T. Binga, in op cit, here translated from the original Italian (IO: Tomaso Binga, sono nata a Salerno nel secolo scorso, ma vivo e lavoro a Roma. Attratta fin da bambina dalla letteratura (le mie poesie risalgono all’età di dieci anni), ho iniziato a lavorare nel campo artistico fin dai primi anni sessanta, ma sono uscita allo scoperto solo nel ’71, nel pieno del fervore femminista, assumendo in arte, ironicamente e provocatoriamente, un nome maschile. Da allora la mia ricerca si è sviluppata, sempre con grande coerenza, nell’ambito della Scrittura Verbo Visiva e della Poesia sonoro-performativa)

[4] Trimarco, published as an article in «Il Mattino», 18 May 1992, with the title Tomaso Binga, in A.Trimarco, Napoli ad arte 1985/2000, Editoriale Modo Milano, re-published in A.Tolve – S Zuliani (editor), op. cit., p. 104.

[5] This is a literal translation of the original Italian, loosing the sound-play with the words: ‘il mio estremo esperimento/è sparare sul commento/rovesciare le convenzioni, azzardare le utopie/pedinare suoni e azioni/intrecciare anomalie»’

[6] S. Zuliani, Binga artista totale, op cit, p. 13

[7] S. Zuliani, Binga artista totale, in op.cit, p. 19

[8] A. Tolve, Nel corpo della parola poetica, op.cit, p. 46

[9] The text by G. Dorlfes was published as the Introduction to the exhibition catalogue Tomaso Binga. Il corpo della Scrittura, Macerata Municipal Gallery, 1981, in Tolve Zuliani, op.cit, p. 85

[10] Moschini, in op. cit., p. 95, the verses are a literal translation for the Italian loosing its play sound with works (“con un solo dito/batto un tasto/ lo stesso tasto batto/ e ribatto ancora/ fino a nove / immagini nuove…”)