The artistic output of Domenico Antonio Mancini (b. Napoli, 1980) is situated within a sphere of conceptual research where the precision of analysis and proof coexist with Socratic irony, the perspicacity of mind, an inclination towards paradox and the provocation with which the artist aims to draw attention to and overturn the parameters of cognizance. Such a practice tends to deconstruct cultural automatisms of attribution of significance, emptying them of common sense, stripping objects of their function to then make them function again and become traces of an artistic and political act for the purpose of producing a more elevated critical integrity.

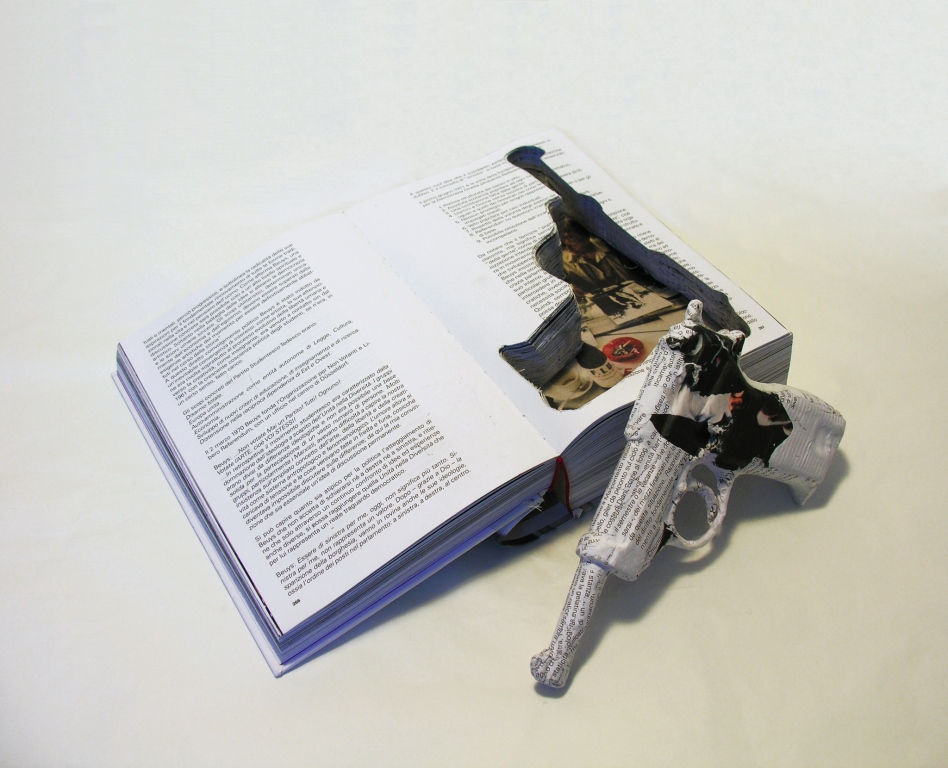

In works such as those presented at the Altre Resistenze (Other Resistances)solo exhibit in 2011 or the works from the 2012 Senza titolo (estintori) (Untitled – extinguishers), Mancini conceives tautologies and redundancies that become strategies for resistance towards the eclipsing and alteration of historic memory. The artist’s quest appears to be a battle against «the paralysis of thought» and his works are systems of opposition to the rigid structure of perception and communication, as is the case of Per una nuova teologia della liberazione (For a new theology of liberation). This work from 2011 would have the texts of Aristotle, Tolstoy or Beuys evolve into the weapons and ammunition needed to face reality with intuitiveness.

His works are aesthetically clear, sharp and unambiguous. They are presented as syntactic «stratified» structures that enclose various levels of interpretation of the work – from more obvious and concrete to deeper and more articulate ones. La ricostruzione dell’archivio di Lia Rumma – 2013 – (The reconstruction of the Lia Rumma Archives) is proof of this. In fact, it is an apparently descriptive work in which the artist uses a “mnemonic reproduction” of a real place to set up a field of exploration, allowing the public to enter into the areas of his creative process. Usually these areas are used to analyze super-temporal and multi-disciplinary issues that facilitate the formation of individual and collective identities.

You received your degree in painting but you define yourself as sculptor. How do these two aspects of your work co-exist?

To indicate an environment in reference to my way of making art, I find it using the definition Michelangelo used for sculpture very thorough. He stated that it was like «subtraction», an act of synthesis. Although my work is not necessarily sculptural, it is most definitely a work of synthesis. It is not limited to the subtraction of material, as is the case with Michelangelo’s marble, but the removal of information as well: it tends to detect the point in which a work is no longer merely a vehicle of information and becomes a producer of sense. This can be seen in my recent paintings as well. The works presented this year for MIART at the Galleria Lia Rumma booth do not develop with the additive procedure used in painting – even though they are oil on canvas. In fact, these are paintings that do not evolve from urgencies of a pictorial nature. After all, I apply a method of removal in my drawings. This practice of marking the spaces I am working on is for the purpose of understanding which elements (not necessarily of a physical nature) are essential, the space I am examining. An example of this is the works in cardboard which are the restitution of the experience of that imaginary place where the process of subtraction takes place.

As a «Michelangelophile», do you think that the real is actually a prisoner of the superfluous? Do you tend to eliminate excess during the creative process?

I wouldn’t quite call it a prison; it’s more as if reality can be created within the superfluous. A quest for the sublime – which is the ultimate purpose of art – calls for an effort to make a critical observation of the excess manifested during the process of subtraction. It’s like needing the dark to see the stars.

What do you hope the public will understand about your work of condensation?

I usually hope that the need for critical observation conveyed in my work can be recognized and that it can lead the spectators to develop their own critical strategies for the purpose of obtaining a more insightful view of reality. I have no rules to provide, just the need to suggest a practice.

Are you a news artist? Or are you a political artist?

I am an artist. I do not particularly like prefixes and suffixes added to the word ‘art’. There is definitely a close relationship between reporting, politics and many types of art which explore issues regarding real life. However, this relationship is as tight as it is delicate and risky. Certain methods and procedures must be thoroughly observed. As an artist, I do not feel the urgency to inform. My task is to produce an experience of things, an experience that cannot disregard information and the precise methods with which it is gathered – even though it must be disengaged from it. The connection with politics is «natural» in the Aristotelian sense of the term. I am not interested in activism in the strictest sense but I lay claim to the responsibility we each have to our own civitas, for a perceptive crossing of reality.

What role does art play in the face of socio-political issues like those in the Mediterranean?

As I was telling you before, I think we all need to take our responsibilities towards the society in which we live and if we – as artists – claim to possess a distinct skill of observation or critical synthesis, then we must accept the duty to show how this is a necessary practice in everybody’s daily life.

In regards to the current situation in the Mediterranean, it is only the extreme effect of hundreds of years of colonial policies in that res nullius which has always been Africa in the minds of «first world» countries. The only perception we have of the immigration crisis is what the media feeds us of recent (and less recent) stories from Lampedusa and the tragic casualties which only make it to mainstream news coverage when the numbers are outrageously high. The fact is there have been decades and decades of departures and missed arrivals as well as hundreds of thousands of victims/ individuals .

Your new exploration focuses on the Mediterranean. How did it come about?

It is based upon, as is often the case, my personal needs which are later converted during the artistic process – eliminating the autobiographical aspect to leave room for the most objective reflection possible. The need is for recovering a cognizant relationship with the sea and to arrive at a more insightful view of «Mare Nostrum», a sea that belongs to all of the cultures who embark on it. None of these can exist without the others. They are all the results of the gradual process of exchange, fusion, collision and a natural flow that certain kinds of politics insist upon funnelling and controlling. The motivation behind my work on the Mediterranean issue can be found in that invisible dimension that people must learn to see.

For as neutral, cold and far from the ‘heat’ of reporting your work is, at times it risks becoming interwoven with the nostalgic aspect of history. What value does memory hold in regards to your research?

I think that memory is place where awareness can grow. It is not the memory of the past but the construction of our way of being in the future. Personally, I am not nostalgic and my work is not linked to recollection. I prefer the possibility of using it as an opportunity to ponder historical events from the distant past even though it is merely a way to deal with issues that are absolutely metahistorical.

You also worked on memory for the “pictorial” work presented this year at MIART…

The Landscape I proposed to MIART is a work on the mechanisms of the visual experience, the relationship between image and memory and the risk that an overproduction of images could result in a limited view of memory of reality. In essence, this is what happens when we look through a tool like a camera or video camera. We lose the experience of the real fact and produce an artificial recollection. The intention was for reflection on the landscape, on the relationship we build with the spaces we cross through. The choice of oil and canvas was the result of the relationship we have built between painting and landscape through the history of art due to the fact that I believe that landscapes find their maximum expression through painting. However, even though it presents technical coherency, the work is not based upon pictorial necessity or a need for representation through painting.

At this time, some urban landscapes are losing that sense of the facts they should be illustrating. The work for MIART refers to the Streetview image at the corner of Via De Amicis in Milan where Paolo Pedrizzetti took his photograph of the individual holding a pistol during the conflict at a 1972 demonstration. This image became symbolic of Milan during that time. The photo doesn’t only capture the moment of a criminal act. It immortalizes the extreme decision of an 18-year-old boy to risk his very life to carry out his revolution. And yet again the task of «removing», the lack of representation of the landscape is actually the denial of the landscape itself. It is an invitation to construct the scene and a plea to create an experience through the discovery of the place and the event which took place there.

Your solo exhibit is being inaugurated on 27 May at the Galleria Davide Gallo in Milan. Can you tell us a little something about it?

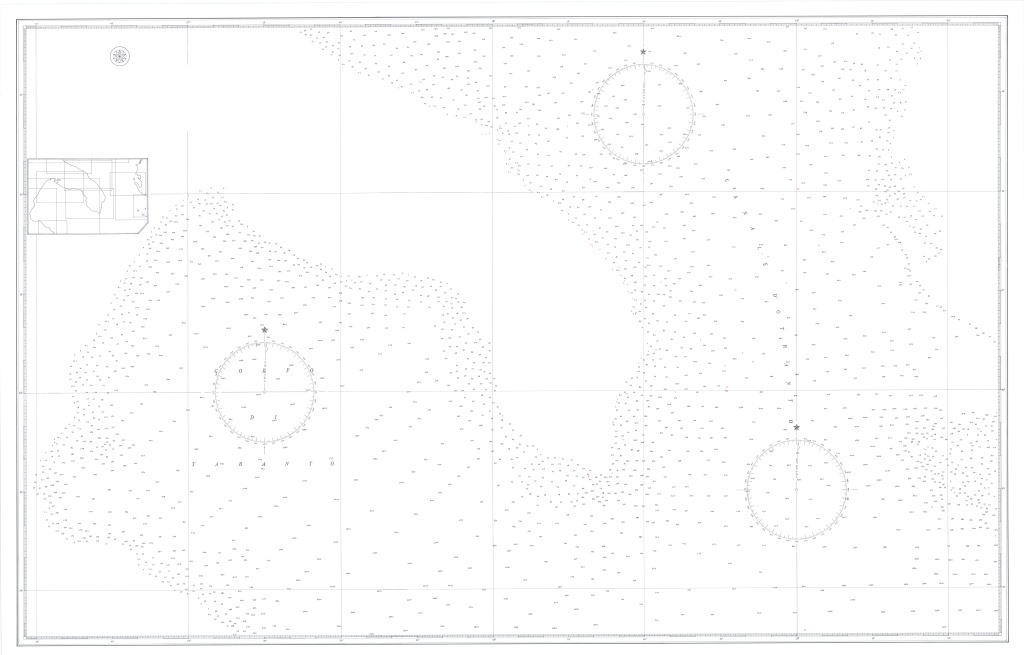

It is an environmental installation about the boats that were lost or sunk in the Mediterranean – another example of large-scale trafficking we know so little about. A hidden story that is apparently no longer newsworthy. It is the story of the relationship between large business groups and criminal organizations regarding the disposal of enormous quantities of radioactive material and toxic waste between the late 1970s and the 1990s. It is obviously a pretext to tackle the issue of the Mediterranean. It is an ecological piece in the literal sense (a debate on the environment), a study that begins with Avviso ai naviganti (Notice to sailors), the first system I adopted to learn more about the area I had decided to work on. In that case I used nautical charts from different areas of the Mediterranean as tools and I redesigned them – keeping only the frames and the depths of the water, the authentic representation of the sea on paper. I then inserted the verified information regarding the shipwrecks dating back to the 1980s.

Which area of the Mediterranean did you focus upon this time?

Southern Calabria between Sicily and the coasts of Albania and Greece starting with the investigation of the «Ships of Poison», material (which has disappeared, in part) that tells the story of complex inquests and suspicious deaths. There are traces as uncertain as those loads buried at sea. Based upon this documentation, obviously, the issue I examined is an incentive to begin a series of reflections on broader topics; I am referring to the Mediterranean because it is the area I know best although the issue is most definitely global.

Domenico Antonio Mancino, Gallo Gallery, Milan (Via Farini, 6), May 27, 2015 (opening) – July 15, 2015

images (cover 1) Domenico Antonio Mancini, Avviso ai Naviganti, ink on paper, detail, courtesy Galleria Lia Rumma, Milan/Naples (02) Domenico Antonio Mancini, landscape 57.31h,79.89t, 2015, oil on canvas, 92 x 130 cm. courtesy Galleria Lia Rumma, Milan/Naples (03)Domenico Antonio Mancini – Ricostruzione dell’archivio di Lia Rumma (faldoni, mensole, sculture in carta), 2013, drawing on paper, environmental dimensions: 386x627x393 cm, edition of 1, photocredit Giusva Cennamo Studio Fotografico Primo Piano. courtesy Galleria Lia Rumma, Milan/Naples (4) Domenico Antonio Mancini, Per una Nuova Teologia della Liberazione, 2011, book and papier-mache (5) Domenico Antonio Mancini, Altre Resistenze, 2011, papier-mache, Costituzione Italiana, wood, lamps, sound, variabile dimensione. photocredit Danilo Donzelli, courtesy Galleria Lia Rumma, Milan/Naples (6) Domenico Antonio Mancini, Avviso ai Naviganti # 08 (Canale d’Otranto), 2014, ink on paper, 92 x 142,5 cm. courtesy Galleria Lia Rumma, Milan/Naples