Federica Di Carlo’s work always exists at the interface of aesthetics and science. To what extent can art be said to approach experimentation and how much does (scientific?) observation underlie an artwork? Her environmental installations are characterised by an alienating dynamic, always complex but never obscure. With her we are going to try to better understand the precise relationship between contemporary art and scientific research. Listening to Di Carlo means being open to a mediation that must not be taken for granted, it means perceiving the humanistic nuances of intricately structured science, as well as tuning into the more scientific nuances that go hand in hand with ethereal aesthetic ideas.

Fabio Giagnacovo: Your works always merge aesthetics (the science of sensations, as someone said) with science (the outcome of thinking, in its most generic definition). Even so, we can see a connection between these two extensive human existential realms, often regarded as absolute opposites. It makes one think about how, on the one hand, thought becomes spirit and, on the other, matter, and that these two forms taken together give meaning to thought itself, closing the circle. The greatest scientists of the past must be called ‘artists’, just as many artists, from Leonardo to the present day, are in some way ‘scientists’. What does it mean to work simultaneously on these two conceptions of existence, so similar and yet so different? Is there a process of mediation involved? Don’t you feel overwhelmed by the complexity of things – things which aren’t pure spirit, just as they aren’t pure matter?

Federica Di Carlo: I believe the search for the absolute has always been something that both scientists and artists pursue and, perhaps, the confusion is caused by these two distinct categories.

Being overwhelmed by what we see around us is necessary and a way of expanding knowledge. It’s a vital act towards which I feel constantly drawn and towards which I see them pushing themselves as well through scientific language.

Working on these two things is actually a natural process because they coincide, they aren’t separate. They both point towards nature, towards contemplation, towards the vitality of the world, the vitality of the universe.

It’s a spark that I think we have carried within us since the birth of the human species and that we have simply anaesthetised a little, but which is fundamental to our lives.

Following on from the previous question, let’s be a bit more specific. You often work through environmental installations, with ever-changing media. They’re governed by the fascinating ‘laws of nature’, such as the secret of light but, at the same time, find meaning in the eyes and body of the visitor who experiences them, without ever being remotely didactic. Although based on scientific concepts and experiments of incredible significance, you always seem to prefer being to knowing, the purely scientific value of things dissolves into cultural value while remaining strongly characterised by it. What’s the signifying process that leads to this outcome which, while being alienating on the one hand, on the other appears incredibly natural (or perhaps it would be better to say: incredibly human)? To what extent do you think scientific progress has to do with anthropology?

I privilege experience. I prefer emotion to knowledge as it’s being put to me now.

Experiencing something around us is also an imaginative process by which we arrive at knowledge.

So I actually start from ideas related to the physics of nature, the rules of the world, but only as a starting point from which to talk about how our emotions are transformed by being in the world.

I don’t explain science. I don’t want to explain it, it’s perfectly self-explanatory.

Instead, I try to remember that we are elements united with the whole, to remember that when we stand up and walk we’re experiencing gravity and then we experience the joy of being able to run, to play with others. It’s all deeply and inextricably linked so, yes, it absolutely has to do with anthropology. Every scientific discovery, every visual discovery, even those made by artists, has created a system of interlinked changes that have led to an evolution, or sometimes involution, of society.

This has always been the story of man.

I get the impression that this new era has forgotten that actions necessarily have consequences, that every action or non-action produces change and, in this apathy, I think that both art and science still play a crucial emotional role.

And that they shouldn’t be exploited, however, by the concept of power or by the high structures that have always used them at will to exert a false dominance over their own kind.

You once said, “I think we are both on a mission – scientists and artists – with the same purpose: to understand, to know why we are here, why we feel things and what the balances are that make us exist in the world. Each of the two worlds contributes in different ways.” You have often found yourself collaborating, as an artist, with scientists, somehow making these two different worlds overlap. What is the human relationship between the proponents of these worlds? And, from your experience, how does the man of science position himself vis-à-vis contemporary art?

You once said, “I think we are both on a mission – scientists and artists – with the same purpose: to understand, to know why we are here, why we feel things and what the balances are that make us exist in the world. Each of the two worlds contributes in different ways.” You have often found yourself collaborating, as an artist, with scientists, somehow making these two different worlds overlap. What is the human relationship between the proponents of these worlds? And, from your experience, how does the man of science position himself vis-à-vis contemporary art?

My relationship with scientists and the world of science has always been for the most part very welcoming. I believe there are scientists who are more open to hybridisation, to contamination, and scientists who are locked in their watertight compartments; depending on who you meet, you can find a way forward or a dead end. When one comes across a way forward, even when one has a spiritual encounter with such people and at these moments, a fruitful exchange is truly created.

Some people believe that the exchange must have a utility immediately in terms of matter and form, and this is often the case, in the sense that scientists provide me as an artist with a technical solution to an artwork. At other times, however, an exchange without a material solution is much more important and intense.

When the conversations reach such technical possibilities, when I insist with them on something they tell me that can’t be done… we both help each other discover a new possibility that didn’t fit into the established patterns of either one of us.

We live in a society that, ideologically speaking, is extremely lukewarm, disinterested and levelled to an often incoherent common horizon. On some issues, however, there’s an incredible and grotesque polarisation, and here I’m thinking of science. If, on the one hand, rampant denialism goes as far as to propose a dangerous anti-scientific worldview, on the other hand, we find real faith in science, with its dogmas, forgetting that it’s fallible and always mediated by human action and though like all human practices. It’s impossible for us to reason about the pure absolute. To continue with these similarities, contemporary art also experiences this extreme polarisation. Moreover, this isn’t only in somewhat ‘theoretical’ terms, but also in practice. On the one hand we find a certain return to the origins linked to the climate crisis and, more generally, to the crisis of contemporary man but, on the other hand, to quote the experiment echoed in your project Volevo il Sole (I Wanted the Sun), the (almost divine) attempt at nuclear fusion to recreate an artificial Sun on Earth. What are your thoughts on this?

Wanting the sun, trying to break free from what keeps us alive is, in itself, an action that brings about a crisis and this is the crisis of humanity – it’s the crisis of society.

Society, art and science are just words invented by this human species to believe we are a different, separate, superior species to animals or plants and leads us to make very serious mistakes.

The fact of creating culture, producing culture, making art, creating technology and tools with ingenuity, that allow us to live increasingly better lives, and then doing science as well, has led us, at times, to get the balance, the calibration of this action wrong, and at a price.

It’s as if by trying to be God we have forgotten that if we play God, then we must be in harmony with everything else. We’re clearly facing a step in evolution or involution, a step – using maybe an extreme term – towards extinction.

This is because we’re the only species that plays with and manipulates all possible matter contained within this celestial sphere that has given us life; a species that’s also naive in some ways and doesn’t seem to learn from previous mistakes. This is the thing that has amazed me to this day and which I can also see within scientific systems, where scientists are the first to say that they don’t know everything, that they cannot be certain that when they light their ‘sun’ on earth everything will be safe.

This return to the sacralisation of science is mainly the fault of the media’s manipulation of information for the audience, to make numbers, nothing new here, and yet much more dangerous today than yesterday because of social, artificial intelligence. Covid-19 was a successful experiment, making us believe that everything was under control because science represented an extremely safe place. Nothing could be further from the truth. Science, like art, grows out of mistakes, out of repeated failures, and must make these mistakes in order to progress.

Or, like the film Oppenheimer, which reminded us that in order to make an atomic bomb, scientists like Marie Curie naively contaminated themselves with radiation which then killed them.

If it can’t be seen, this doesn’t mean that it’s not acting on us, and so to believe that culture or science is something to be used and then thrown away as needed is surely the biggest mistake of mankind at the moment.

You have attended several Fine Arts Academies (Rome, Bologna, Barcelona) and spent time in some of the most important European cities. Not long ago, in Italy, you won the Italian Council prize, research section. In your comings and goings, have you noticed any important differences between how art is taught or, more generally, in the art system, between Italy and other European countries? Is the post-graduate “salt pan” (sorry, post-diploma) an Italian prerogative or is it the way of the world?

I certainly continue to observe a distance between Italy and the rest of Europe, America or, in any case, all those countries that have always considered and still consider culture and contemporary art as an asset, as well as providing economic value for their country. We don’t do this and I don’t see any great signs of improvement at the moment, apart from small “fires” lit by artists after Covid-19. These artists realised they’re totally invisible in the eyes of the state and have no role at all in society, despite the fact that the works they produce in life, or which are recognised after their death, fill empty boxes that we call museums. Unfortunately, this is mainly an Italian problem.

But I also believe that if this has never changed, it’s because we haven’t analysed our role in this or the part we play that hasn’t generated change. I believe this is because artists are extremely subservient to all the dynamics of the art world, the ‘contemporary art’ system, but this is also true of modern museums, which are subservient to political dynamics. I see artists who don’t value themselves as they should and then, of course, others giving themselves absurd values.

But it’s incredible that today’s museums don’t have an internal regulation stating, as a matter of course, that artists should be paid when they’re hired to do an exhibition of their works. There is no register of artists, no register of curators and our ministry dedicated to this sector, now with the new government, is about to be made invisible again or merged with other ministries.

While those in show business take to the streets, we don’t do this because it’s not seen as “elegant”. What a great opportunity we’ve lost.

I think back to the Venice Biennale of 1968 when artists went on strike and covered their works. If we’re constantly afraid of not being seen enough, then we deserve this.

If we don’t change the system, the system won’t change given the current politics that is in charge and continues to have greater consensus than the previous forms which, perhaps, weren’t very effective.

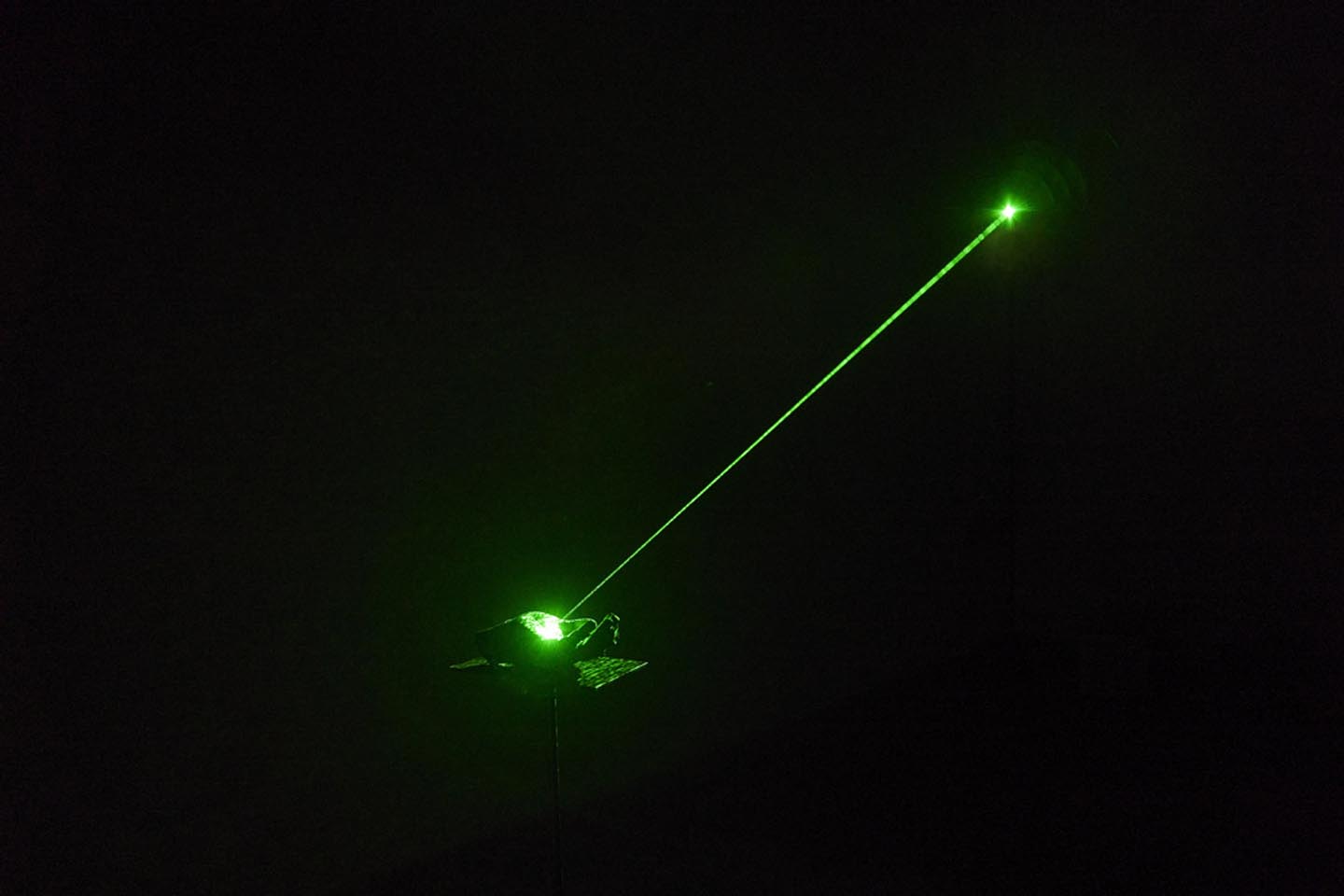

images (cover – 1) Federica Di Carlo, illustration by Nikla Cetra (2) Federica Di Carlo, «Flow», Villa Galileo, Florence, 2023, ph. Jacopo Nocentini (3) Federica Di Carlo, «We Lost The Sea, Arsenale della Marina Regia», Palermo, 2018, ph. Lorenzo Bacci (4) Federica Di Carlo, «Volevo il Sole», PostmastersROMA, ph. Giuliano Del Gatto (5) Federica Di Carlo, «Vivo alla Ceramica», Ex-fabbrica Pagnossin, Treviso, 2019, ph. Giacomo Vidoni (6) Federica Di Carlo, «Come in Cielo», Così in Terra, Serlachius Museum, Finland, 2018 (7) Federica Di Carlo, Illustration by Nikla Cetra

“Survive the Art Cube” is a series of interviews with artists from different generations. The title borrows from Brian O’Doherty’s most famous book to echo its critical slant. It aims to better understand how these artists perceive the analogue-digital space in which we are immersed and our contemporaneity, what sense and importance artistic space has today and what sense it makes in our present to make an artistic journey. Dark times call for reflection on reality and only artists, perhaps, can open our minds.

Previous Interviews:

Interview to Giuseppe Pietroniro, Arshake, 07.12.2023

Interview to Francesca Cornacchini, Arshake, 14.11.2023

Interview to Enrico Pulsoni, Arshake, 09.11.2023

Interview to Marinella Bettineschi, Arshake, 15.10.2023