Tomorrow Arshake will relaunch an interview by Luca Zaffarano of the multi-faceted artist Bruno Munari dating back to 1987, the year after his first retrospective as an artist in Italy realized at Palazzo Reale in Milan. Today Luca Zaffarano is one of the best-qualified people to speak of Bruno Munari’s art. Over the years he has built up the munart.org website/archive, containing in-depth information on the life and oeuvre of the artist, constant updates on all presentations of his work, interesting facts, documents, information regarding collectors of his pieces and much more. Over time the archive has become a reference point for researchers, enthusiasts and experts. I met Luca Zaffarano in 2013 when I came across the site while looking for information and material for an article on Bruno Munari. At that time Zaffarano was working with the photographer Pierangelo Parimbelli on a study of Munari’s Macchine Inutili (Useless Machines), which became an essay in text and images published on Arshake in five instalments over the course of 2014 (Bruno Munari and the Useless Machines) and in concomitance of one large retrospective, Munari Politecnico, depicted at Museo del Novecento in Milan. A while back I stumbled upon a 1987 interview of Munari by Luca Zaffarano. I was immediately struck by the desire to relaunch it (in Italian and English), in order to echo the thinking of a visionary artist who is today more current than ever. I contacted him only recently, and once again my request comes at a timely moment: one of Bruno Munari’s Macchine Inutili and some of the series Forchette Parlanti, has just been acquired by the Centre Pompidou in Paris. I asked Luca Zaffarano a few questions to re-set the context of the interview, but also to frame his role and that of the archive in following the work and the fortune of Bruno Munari, shaping one of largest archive hosted in a corner of cyberspace, available to all.

You met Bruno Munari in 1987. At what stage in your research did this meeting take place? And who was Bruno Munari for the public and the art world at that point?

I met him when I was a student. At that time I was extremely interested in electronic music (I graduated in computer science several years later in Milan, with the current head of faculty, Goffredo Haus, who was then leading the digital music laboratory). For me, Munari was an interesting figure because of his ability to be interdisciplinary, and I was amazed by the fact that he had associated with people like Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna and John Cage at the legendary RAI Studio of Phonology in Milan. He broke down colours with polarisations, while they dismantled musical tones with concrete music, synthesised sound or prepared piano; all were revolutionising the language. I really liked his books: apparently simple, but in fact very theoretical. With an Anglo-Saxon talent for explanation he explained in detail how he went about his work and the results he obtained. He had an “open-source” approach ahead of his time. He was an artist who used a scientific method, enriched by imagination, but always verifiable. His research was closely linked to the work of the European avant-garde in the 1920s and 30s, which he then further developed in a kind of long-distance dialogue.

How well-known was Munari to the public and critics in Italy and abroad at that time? And how well-known is he today outside Italy?

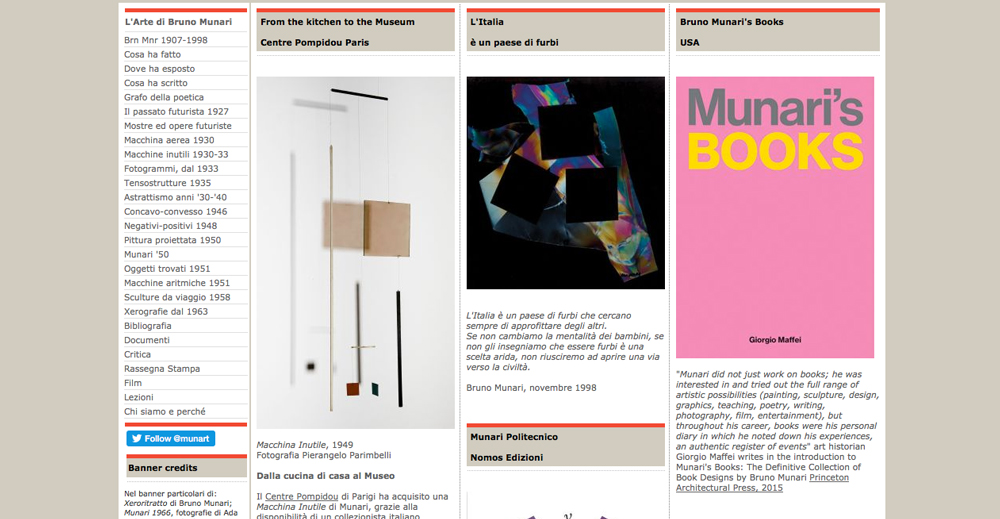

In Italy, Munari was never considered an artist, in my view, until his anthology exhibition in 1986 at Milan’s Palazzo Reale (when he was almost 80). This show was keenly desired by Enrico Baj, who found it shameful that the city of Milan had not yet dedicated a homage to such a major figure as his colleague. Further proof is that today, despite the efforts made by former director Marina Pugliese, the Museo del Novecento in Milan does not possess a Macchina Inutile by Munari. Overseas, however, there has always been a fair amount of attention paid to his work. I recently contacted a buyer at the Pompidou Centre about the possibility of acquiring a 1949 Macchina Inutile (it hung for many years in the artist’s kitchen, and was beautifully photographed by our own excellent Ada Ardessi). I emailed the curator at New Year, when she was on holiday; a few days later she had spoken to the director and by 7th February they had already put in place the procedure for the acquisition. The process has just concluded, following clearance by the Ministry of Fine Arts. This is the second Macchina Inutile to become part of a foreign museum collection; the first, in 1952, was donated by Pontus Hulten (a great admirer of Munari) to the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. A process so quick and simple that it would be unthinkable in Italy, and I haven’t even gone down that route, for lack of trust. It’s a pity, I believe that in nineteenth-century Italian art, Munari’s importance is comparable only to Marinetti; he’s our Warhol before Warhol came along, as American curator Vivien Greene put it.

You’ve been occupied by Bruno Munari for many years. Your archive is now an extremely important reference point for knowledge and circulation of Munari’s work. Can you tell us how you manage his work and his memory, as well as building an archive which you generously make available online?

The archive owes a lot to the philosophy of knowledge sharing and to certain major web-based projects (minimal in appearance yet dense in content) such as ubu.com e monoskop.org. The idea is this: the world of art is opaque, and opacity serves to confuse, to sustain actions which are halfway between indirect finance and insider trading. You may not like it, but the art world today operates in this way. Putting all the documentation about what Munari really achieved online allows people to understand whether he was really an important figure in twentieth century Italian art and on the international scene, and why. The sharing of knowledge serves to make public what has already been done, so that those who come after can start from these results and continue to new things, however minimal.

What are your aims for the future of the archive?

First of all, continue to work on the munart.org project, which has now become a kind of hub, a dispenser of free services: curators write (even important ones, such as Biennale directors) to find out where to find a work that’s on loan, scholars looking for documentary confirmation, magazines looking to publish images, etc.

Another extremely interesting project would be to hold the retrospective that no one has yet held, we could call it the Munari exhibition that I personally – and I think many people – would like to see, obviously starting in Italy; but the Italian art world is still very pre-modern, what you can do doesn’t count, only who you are or who your sponsor is.

Munart.org

images (cover 1-4) munart.com, snap shot from website (2) Bruno Munari, «Macchina Inutile. Omaggio a Calder», 1949 circa. nylon, wire, celluloid and aluminium forms private collection, Reggio Emilia, Italy (3) Munari, «Macchina Inutile», 1949, Metal, perspex, wooden rods, nylon, Centre Pompidou, Paris, photograph by Pierangelo Parimbelli (2016)