Invideo – International Exhibition of Video and Cinema Beyond has just concluded in Milan, after four days – 17 to 20 November – devoted to the most recent video productions. Founded in 1990, before the birth of the internet and the spread of digital media, Invideo this year reaches its 26th edition, continues to resist the mutations in visual culture generated by the web and today remains one of the most important exhibitions of audiovisual experimentation. Invideo’s strength lies in the attention paid by its directors, Romano Fattorossi and Sandra Lischi, to the most wide-ranging variants of video, from its most cinema-like forms to its fusion with internet culture; so much so that one of the foci presented this year was the relationship between art and video game, curated by Roberto Cappai.

The theme which forms the basis for the Invideo 2016 programme (curated by Elena Marcheschi) is seduction, naturally encompassing the most disparate interpretations of the word, from the seduction of a look to that of the body, as well as that most obvious of seductions: the allure of technology in the age of technoculture.

[vimeo id=”140763904″ width=”620″ height=”360″]

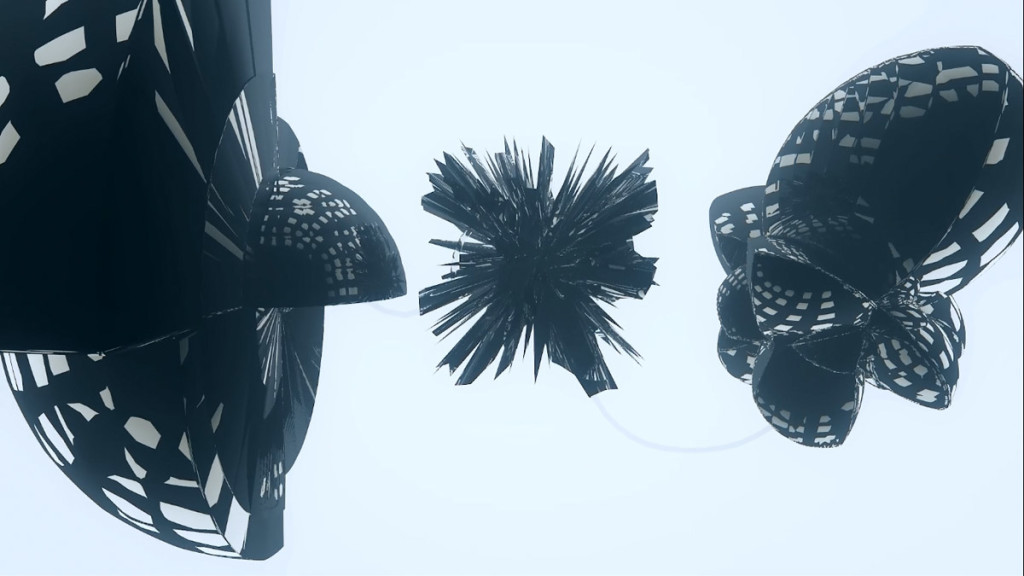

To this end the exhibition ranges from amateur videos appropriated from social networks and assembled by Wildlife Control in Particles (2015) to spectacular graphic elaborations of landscapes deconstructed by Persijn Broersen and Margit Lukács (Establishing Eden, 2016); from Tymon Albrzykowski’s painting in film (Ink Meets Blank, 2016), declared to be a homage to Arnaldo Ginna and Bruno Corra’s experiments a century ago, to the abstract brushstrokes of Daniel Iván’s 3D animation (Haiku, 2015).

There is also a more fictional strand which brings video closer to cinema, and it is no coincidence that elsewhere the talk tends rather to be of “short films”, such as the Festival International du Court Métrage in Clermont-Ferrand, to which Invideo pays tribute with a focus on founder Georges Bollon. In fact the Under 35 prize, awarded to young artists since 2007 by Invideo, this year went to a fiction-type work, Hotaru (2015) by French film-maker William Laboury: an experimental science-fiction piece which addresses a theme more or less explicitly present in many of the works seen in Milan: the transformation of human identity, its intellectual faculties and its passions, in the new technological age.

[youtube id=”nkaE62lE1GA” width=”620″ height=”360″]

The same theme is subtly alluded to again in Antoine Dalacharley’s complex animation in Ghost Cell (2015) – already a prizewinner at this year’s Clermont-Ferrand festival – which transforms Paris into a spectral city where a dense network of white lines (the web?) transfigures and dehumanises everything. Similar reflections are echoed in the work of Alessandro Amaducci, the Italian theoretician and video artist to whom Invideo dedicated a retrospective: electronic music and female bodies moving in imaginary settings incarnate a new digital identity, in precarious balance between the human and the virtual.

The variety of languages and techniques seen at Invideo reflects the enormous array of possibilities offered by current technology and outlines a scenario which would have been unthinkable until a few decades ago: on one side the fact that we can all produce a video using extremely accessible and user-friendly tools; on the other the development of highly advanced and complex software which can produce incredibly sophisticated effects. The very possibilities presented by the use of computers make animation one of the major emerging strands. Closing the international selection, before the finale dedicated to the screening of Love is All. Piergiorgio Welby, autoritratto by Francesco Andreotti and Livia Giunti (2015), there was a showing of the latest video by Alain Escalle, the great expert of computer animation and author of works nourished by art history, in which paintings are spectacularly brought to life. In Final Gathering (2016) Escalle abandons hyper-realistic settings and brings painting back to its most material aspect, creating sombre atmospheres whose only inhabitants are evanescent shadows.

To complete the Invideo programme, two video/music performances took place in Thursday and Saturday evenings, by Chilean artist Matias Guerra and the Milan design studio KARMACHINA (with music by Fernweh) respectively. Interestingly, both were inspired by historic cinema figures, Stanley Kubrik and Maya Deren; the live soundtracking of video images led the audience to an experience far more immersive than simple contemplation.

[vimeo id=”175861835″ width=”620″ height=”360″]

After four intensive days of screenings and encounters, it only remains to wonder what the future of video will be, or rather, given the certainty of its longevity and pervasiveness, it might be better to ask how channels and methods of consuming it are changing: if video today is literally within reach – indeed, within the reach of a click – the involvement of the viewer becomes increasingly urgent.

images (cover 1) Persijn Broersen, Margit Lukács, Establishing Eden, 2016 (2) Wildlife Control (Neil and Sumul Shah), Particles, 2015 (3) Daniel Iván, Haiku, 2015 (4) William Laboury, Hotaru, 2015 (5) Antoine Delacharlery, Ghost Cell, 2015 (6) Alessandro Amaducci, Pagan Inner, 2010