In her Catalogo storico devoted to the entire output of Giovanni and Vanni Scheiwiller (Milan, 2013), Laura Novati also gives prominence to the precious nature of the artist’s books commissioned and published by Vanni. In this respect she explains: “They are published in a period in which there’s a market for exceptional graphics, before the market is altered by inept or discreditable systems of artists and gallerists”.

Indeed, these are years in which Vanni’s catalogue includes not only the “great” engravers, starting with Bartolini and Morandi, but also, thanks to Vanni’s wife Alina Kalczynska – an accomplished artist whose own artist’s books are soon to be brought together in an exhibition – is enhanced by the presence of extremely significant items, the results of the work of chisels and burins on planks and slabs in Alina’s native country, Poland, and previously included to embellish the Scheiwiller booklets.

However, in confirmation of the fact that the graphic art in general of that period was in no way encumbered by the loss of “aura” used by Benjamin to demonise print multiples of engravings, I’d like to remember a single episode which came back to me and allowed me to recall a catalogue that was particularly dear to me.

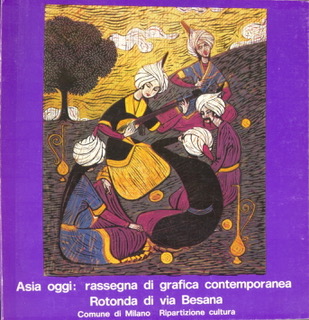

In 1974, a year before he opened his gallery La Casa dell’Arte, my father Efrem Tavoni – who had recently returned from a Grand Tour of the East lasting more than two months – curated an exhibition called Asia oggi at Milan’s Rotonda della Besana. It was a gathering of contemporary graphic art which is still relevant today, and numerous critics, including the most influential of the age, spoke extremely highly of such a memorable exhibition.

In 1974, a year before he opened his gallery La Casa dell’Arte, my father Efrem Tavoni – who had recently returned from a Grand Tour of the East lasting more than two months – curated an exhibition called Asia oggi at Milan’s Rotonda della Besana. It was a gathering of contemporary graphic art which is still relevant today, and numerous critics, including the most influential of the age, spoke extremely highly of such a memorable exhibition.

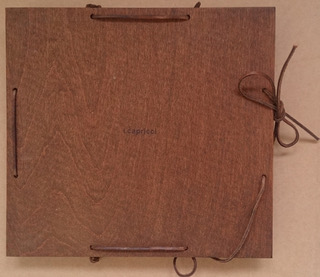

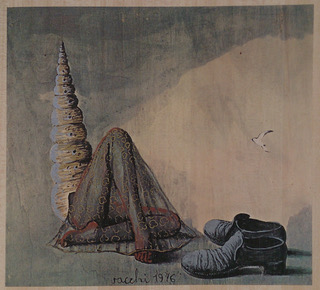

Other major additions to the aforementioned could be drawn from my native city Bologna, where an extraordinary array of artists were published during the 1970s and 80s, expressing themselves through their own gravures accompanied by texts by highly illustrious scholars. Parading through my memory and rising from my stash of paper sources are Morandi’s disciples Andrea Emiliani with Luciano de Vita, more than once; also Pirro Cuniberti with Giosetta Fioroni and various contributors, and – not directly ‘sons’ of Morandi, – first and foremost Sergio Vacchi, an exile who recently left us, and who nevertheless had time in Bologna to publish his Capricci, accompanied by critical texts from poets and scholars of the calibre of Roberto Roversi, Leonardo Sciascia, Paolo Volponi and others, and even a piece by Piera degli Esposti; and, one of the few still with us today, the maestro Concetto Pozzati, who also displayed his ingenious books from the period under discussion in the Italian Pop Art exhibition at the Fondazione Magnani Rocca, which opened in September 2016.

Rather than expending words in an attempt to shed further light on the definition of an artist’s book – a much-discussed concept which continues to invade even the internet without, it seems to me, it being possible or necessary to arrive at an unequivocal terminology to define it, or even merely to describe the form it takes – I would like to underline once again the extent to which those decades were special in every aspect of these singular artefacts, not least the perfection which they often achieved, thanks to the use of the printing press and moveable type, and – almost as the natural consequence – the intensity of the appetite to possess them.

Rather than expending words in an attempt to shed further light on the definition of an artist’s book – a much-discussed concept which continues to invade even the internet without, it seems to me, it being possible or necessary to arrive at an unequivocal terminology to define it, or even merely to describe the form it takes – I would like to underline once again the extent to which those decades were special in every aspect of these singular artefacts, not least the perfection which they often achieved, thanks to the use of the printing press and moveable type, and – almost as the natural consequence – the intensity of the appetite to possess them.

Bringing in also Novati’s assertions with regard to comparisons of the graphic art of that period with that of the present, and linking them with my father’s experience and the Bolognese masterpieces of the day, it is certain that many issues opened up for discussion by Novati have played a significant role in Italian art. One only needs to recall that graphic works by Asian artists – some of them very young – were exhibited for the first time in Asia oggi, and that some of these went on to become – and still are – among the most highly valued of their kind in international auctions.

Nevertheless, in recent years – very recent, in truth – the once depressing scenario appears at last to have opened itself to new horizons: exhibitions of books conceived by artists themselves, promotion in Bologna with the Artelibro festival, now extended to several other cities, attention being paid to these books even by some of the numerous graphic art museums scattered across Italy, greater seriousness on the part of artists and, not least, competitions geared to valorising them. And by doing so, valorising previously unpublished texts or texts by established writers, whether using the printing press or leaving the hand free to suggest the intimate connection between text and image in the interactiveness which has always been, and is still, the true and most expressive nexus at the root of the construction of these books.

Furthermore, certain major libraries have continued to invest in promoting awareness in Italy; libraries which for many years had already conserved these works within their own walls and on their shelves, albeit prioritising works in accordance with the celebrity of their creators and certain well-known private presses. And a few, but significant galleries which until recently took no interest in such artefacts – especially those of recent production – are also taking steps towards the re-emergence of the reputation of artists’ books.

As for the attempt to re-establish in this country a leading role – which seems to be the prerogative of other countries – and re-affirm an irreplaceable position for such books within the Made in Italy movement, in which artistic craftsmanship in all its diversity of expression and type has always been to the fore but which in some sectors sadly appears to have lost its excellence, the task falls – and will continue to fall – to those individuals who are devoting themselves passionately to the matter and managing to arouse interest, thanks to the involvement of eminent and capable friends with the ability to motivate even small businesses and municipalities with few inhabitants but great cultural traditions behind them.

Initially at San Mauro Pascoli – with its prestigious Academy dedicated to the poet Giovanni Pascoli, revered not only for his poetry linked to the metaphor of childhood – there was the opportunity to launch an international competition, which is now concluding, having seen the participation of numerous artists, graphic designers and publishers, and in some cases all three rolled into one.

While the inspiration for the contest came from the undersigned, Andrea Battistini, president of the Accademia Pascoliana and the person who announced it, takes the credit for having acted as its spokesman within the municipality, alongside members of the town’s business community, one of whom – Miro Gori – is also on the panel of judges. The panel also includes, as an expert in the field, artist and teacher Enrico Pulsoni, who deserves high praise for his many merits, not least his generous and ongoing availability. Besides the presence of Pulsoni, the involvement of the Emilia Romagna branch of the Italian Association of Libraries, represented by its current president Federica Rossi, and the director of the Casa Pascoli museum, Rosita Boschetti, gives rise to hope that after the three exhibitions already planned as part of the San Mauro competition, new opportunities will present themselves, even if these are merely further exhibitions.

The precursor of the title is merely to point out that in the case of Torrita di Siena the credentials are greater, but also and especially because Torrita was not virgin territory when it comes to the valorisation of books, both ancient and modern.

Indeed, for several years this small town has promoted its turreted self as Tuscany’s little capital of books. Isn’t it the case, in fact, that Torrita has been claiming the nickname of “Borgo dei libri” for some time? And quite rightly. In the streets, and inside the little jewel of its Teatro degli Oscuri – a former Academy, as so many theatres are, not only in Tuscany but perhaps more so here than elsewhere – books in all their various manifestations are celebrated in stalls, exhibitions and conferences. Last year I was afforded the pleasure of visiting the town, thanks to Gian Carlo Torri, with an extended version of an exhibition I organised for a private gallery in Bologna, the “Ariete Artecontemporanea”. With me there were colleagues and artists, including the authors of books, and with them a small conference was held in that very theatre; the keynote speech, by architecture historian Deanna Lenzi, gave a picture of the glorious past of this place of sociabilité.

However, the exported exhibition, the conference, the fierce young critic Pierluca Nardoni who provided a commentary of the artistic journey in a booklet – a quadrotto, as such items are called here – one of many produced by the great good taste of Fausto Rossi, a printer and publisher whom everyone would like to come across; these were not the only highlights of that trip in May 2016. An exhibition of antique books, superb examples of sixteenth century volumes belonging to Paolo Tiezzi Maestri, an illustrious citizen of Torrita, not only for the post he still occupies as councillor for culture; and another exhibition space in which Enrico Pulsoni displayed his own artist’s books, all different for each other in format and context and equally diverse in print layout and the striking cultural motifs intrinsic to the books. These convinced me then and there that much more could be accomplished in that town, a small place which nevertheless succeeds in effectively combining the public and the private.

And so the idea came about to propose another competition of artists’ books in Torrita, aimed partly at promoting the local area, and linking with the theme – for the illustrations – of abbeys, intended to include monasteries, convents and religious buildings in general, thus extending the theme to an international horizon.

The team dedicated to studying and formulating the competition announcement is formed first and foremost by Carlo Pulsoni, who – in his role as promotor of initiatives whose scope exceeds national boundaries, and his capacity to use various methods for their promotion – can be considered the driving force, in conjunction with Rebecca Carnevali, graduate student at Warwick University. The team unanimously decided that the fabric of the announcement should consider the target of the competition to be artists of books, particularly printmakers, and exclusively “under 30s”.

This criterion is the result of an entire process which involved several of us not only in an attempt to breathe new life into the art of engraving in a broad sense, and in particular in relation to books, but also in the context of a renaissance geared also to opening up spaces – especially for young people – in which a love of art can be combined with financial remuneration.

Only in this way can what last year in Torrita was called “quality micro-publishing”, expressed by artists, some of whom are already well-known, become a model for harnessing the talents of many young artists, appropriately trained in Academies, Universities and other similar settings to this specific market for their work.

There are in fact many artists whom we meet increasingly frequently in various contexts, even on social media, who through lessons, encounters and workshops of various types and genres, have turned their ateliers into places for meeting but also for teaching, and are at last moving in the autonomy they have thus achieved.

In the face of this situation, and understanding the artist’s book to be an excellent product of our own country, we could therefore return to occupying a position of great importance.

But in Torrita, where our initial desiderata have been appeased, we demand even more than that which has already been generously granted with the announcement of the competition by an illustrious institution of the town, the Fondazione Torrita Cultura; we ask not only that the competition should be held every year, but also that a suitable home can be found for it, in which the selected and prizewinning artefacts can be placed and which can act as a museum of the contemporary artist’s book, the only museum of its kind in Italy.

Already, for several of its qualities, Torrita benefits from being a town that receives visitors. It could become even more well-known by enthusiasts of vestiges of the past, or for its hilltop location, or for the deliciousness of its culinary specialities, and more, once it has reached the point of attracting visitors, partly by the regular annual occurrence of its “Borgo dei libri” festival and, in particular, by the presence of artists’ books, in which originality of thought and manual craftsmanship are displayed and offered for the enjoyment of truly exacting connoisseurs. Torrita will acquire what is commonly known as another “image makeover” and a harbinger of major developments to follow.

And for those who decide to remain quietly in the wings for the immediate future, if such a dream might be fulfilled, or rather a miracle which, albeit earthly, is the result of many components, all of them interconnected, recourse to a verse of the Divina Commedia does not seem inappropriate: “Thou shalt discover […] that your art / deserves the name of second in descent / from God” (Inferno XI, 106-110). And here Dante’s phrase fuses with our expectations and brings out all its contemporary meaning: hand printing, and particularly engraving, is also second in descent from God, because, as Dante puts it, art – or the work of man – imitates nature as the disciple follows his master; and since nature is created by God, in other words is His daughter, man’s endeavours are therefore second in descent.

Concorso internazionale Libro d’Artista riservato a giovani under 30 dedicato al tema delle Abbazie

scarica qui il bando

Images

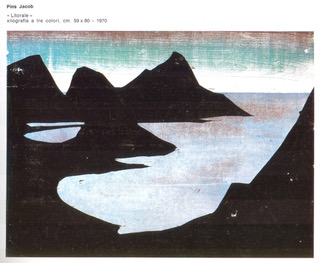

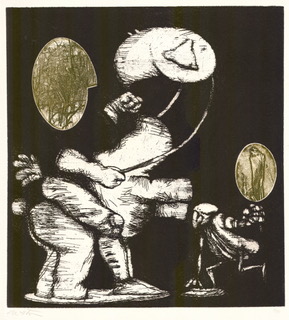

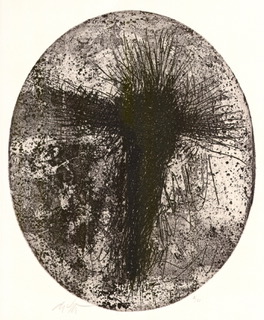

(1) Fondazione Torritta, logo (2) Efrem Tavoni (edite by), «Asia oggi: Rassegna di grafica contemporanea», Rotonda di Via Besana, Milan, cover (3) «Asia oggi: Rassegna di grafica contemporanea», Rotonda di Via Besana, Milan, illustration (4– 4a) Sergio Vacchi, «Capricci», 1972 (5-5a) Andrea Emiliani and Luciano De Vita, «Le cose che volano», 1970 (6) Gianni Castagnoli, «Imperium Europae. Anno Zero» (7) Gianni Castagnoli, «Imperium Europae. Anno Zero», engraving.