The different massive projects by Alan Sonfist, Carl Andre, Alice Aycock, Mel Chin, Walter De Maria, Jan Dibbets, Hans Haacke, Michael Heizer, Nancy Holt, Neil Jenney, David Medalla, Robert Morris, Dennis Oppenheim, Beverly Pepper, Robert Smithson, James Turrell, Günther Uecker, and Seth Wulsin; their European counterparts by Chris Drury, Andy Goldsworthy, Richard Long, Eberhard Bosslet, Nils-Udo, Christo and Jeanne-Claude (including Luca Maria Patella’s Terra animata [1967] and the diverse artworks originated within the Italian experience of Arte Povera); or the proposals advanced by Georgia Papageorge (South Africa) and Andrew Rogers (Australia) – all display, from various linguistic angles, an inclination to work with the things of nature and to turn the world into the artist’s boundless studio. As William Malpas points out “This means the very texture and colour and shape and dampness and springiness and strength and size of moss, for instance. Or a stone. Or a crevice in a rock formation. The way the light falls on a patch of grass, the little bits of dead, yellowish grass on top of the newer, green grass. Pine cones, closed-up. Flowers turning sunward in the late afternoon. These are the things land artists deal with in making art. These are the actualities that artists employ when they create artworks.”[1]

Nevertheless, Barbara Rose, a keen observer of her time, in the fourth installment of her “Problems of Criticism”, rapidly got a sense of the inescapable compromises between this new state of the affairs in art and the art market.[2] Inspired to Brian W. Aldiss’ sci-fi novel Earthworks (1965), the exhibition Earth Works, organized by Robert Smithson in October 1968 in New York at Dwan Gallery,[3] although influenced by a pessimistic stance on the future of the American environmental heritage, represents a first, irreversible encounter with the behemoths dominating the international art market.

This scenario, currently actualized by artists such as Vik Muniz, who has envisaged an array of exquisite projects connected to eco-sustainability and social outcry, applies to a number of contemporary art projects easily touching upon a series of different codes, tools, and places. The mind easily goes to the installation Untitled by Pierre Huyghe, who turned a section of Karlsaue park in Kassel into a biotope containing a statue of a woman (whose head is covered with a bee-hive) and inhabited by two dogs, one of which, a pink-legged greyhound, soon became the symbol of dOCUMENTA13. The mind can also go to the stunning installation, again presented at dOCUMENTA13, entitled I Need Some Meaning I Can Memorize (The Invisible Pull), created by Ryan Gander and placed at the entrance of the Museum Fridericianum: there, the wind embraces the viewer with its biting touch and with a voice reminiscent of vento Matteo’s, a character from the pen of Italian writer Dino Buzzati, is the absolute protagonist of that space, escorts the viewer in experiencing it, and dignifies her emotions.

[1] W. Malpas, Land Art: A Complete Guide to Landscape…, 7.

[2] “Problems of Criticism /IV The Politics of Art, Part III”.

[3] This first encounter was followed in February of the following year by the exhibition Earth Art, curated by Willoughby Sharp at the Andrew Dickinson White Museum at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, which took place from 11 February to 16 March 1969 and marked the entrance of environmental art into the institutional system of art.

This is the second of eight appointments with the critic reflection by Antonello Tolve who retraces the complex relationship between art, technology and nature, by surveying a number of artworks connected to the relation man/environment, from Land Art to Transgenetic Art to Bio Activism. Please click here to read the first part.

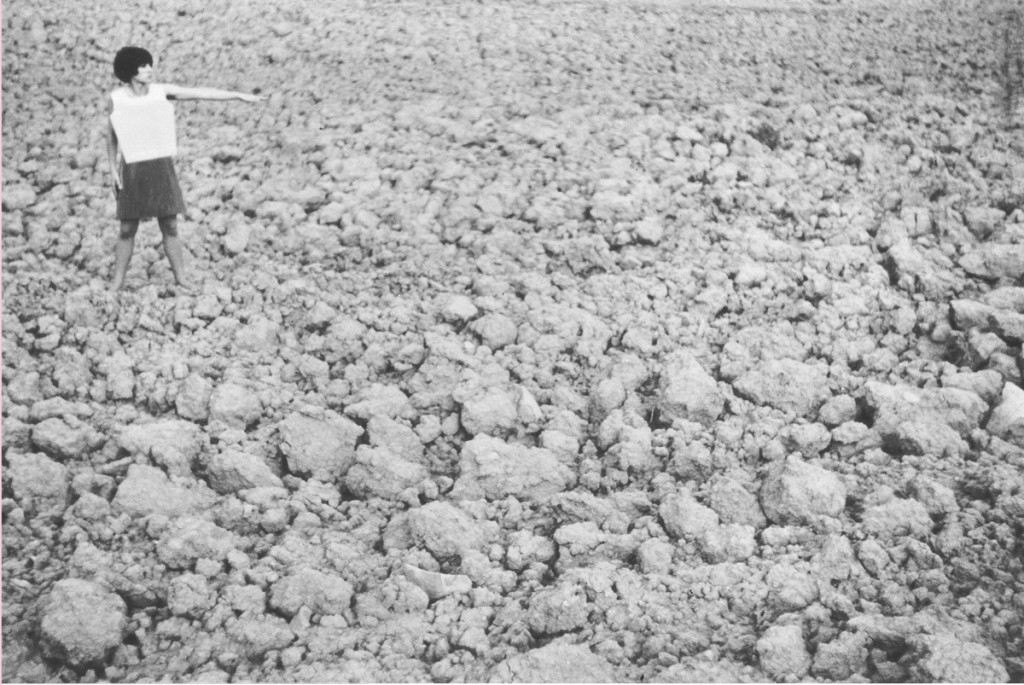

Immagini (1) Luca Maria Patella, Terra Animata,1967, tela fotografica b/n, 125 x 185 cm, courtesy of Luca Maria Patella (2) Pierre Huyghe, Untilled, Documenta 13, 2013