Giulio Bensasson: as young as he is stubborn, and as stubborn as he is interesting. His artistic research, based on absolute themes, is multifaceted in works of various kinds, from installation to photography to sculpture. Listening to Giulio Bensasson means looking at the emerging generation of artists and means being faced with a career, albeit very young, that is very structured.

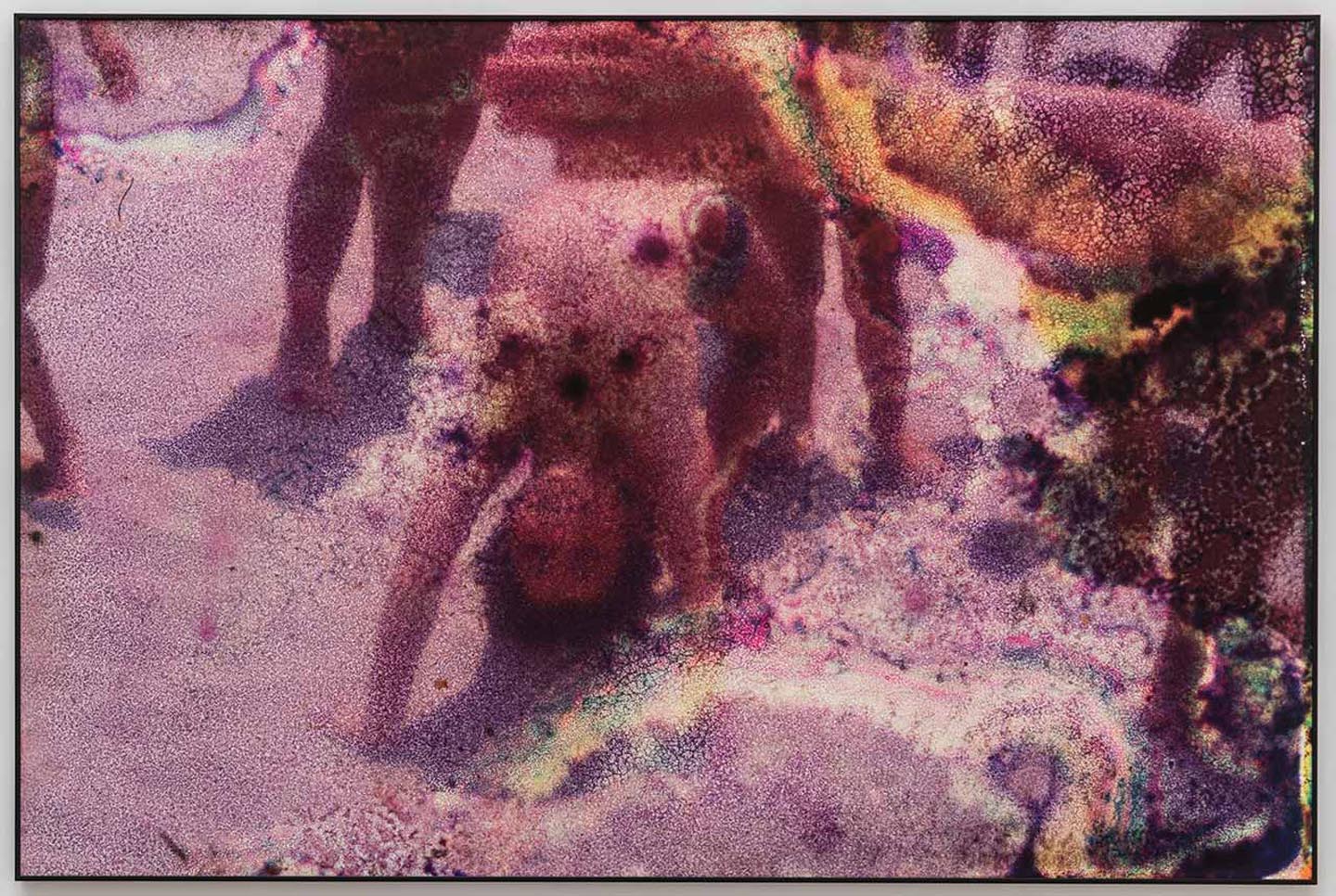

Fabio Giagnacovo: Practically all your works have to do with Time in some way. A time understood as chronos, quantitative and relative to human life, which does, however, reveal its absoluteness, what the Greeks used to call aion. I am thinking, for example, of the ever-growing photographic archive I don’t know where, I don’t know when, in which old photographs that represented a well-defined instant in the past, a memory of time, totally change their existential and essential meaning thanks to the basic coordinates of reality: Space (characterised and very precise, for example it must be suitable for the proliferation of moulds and fungi), and above all Time, which shows itself to be a bit of a co-agent of the work, a bit of an instrument. What does it mean to carry out such absolute artistic research, on an element so pure and impossible to dominate?

Giulio Bensasson: I would not say that all my works have to do with Time, I would rather say that all works have to do with Time. Every artist (and every human being) has to come to terms with the durability of his or her works, both in material terms (and thus their perishability over the years) and in ideal terms. If an idea, work or poetics survives its author then we have won, otherwise we are just part of the vanity of this world. And so I would say that all my research is based on the investigation of our limits, time being just one of them.

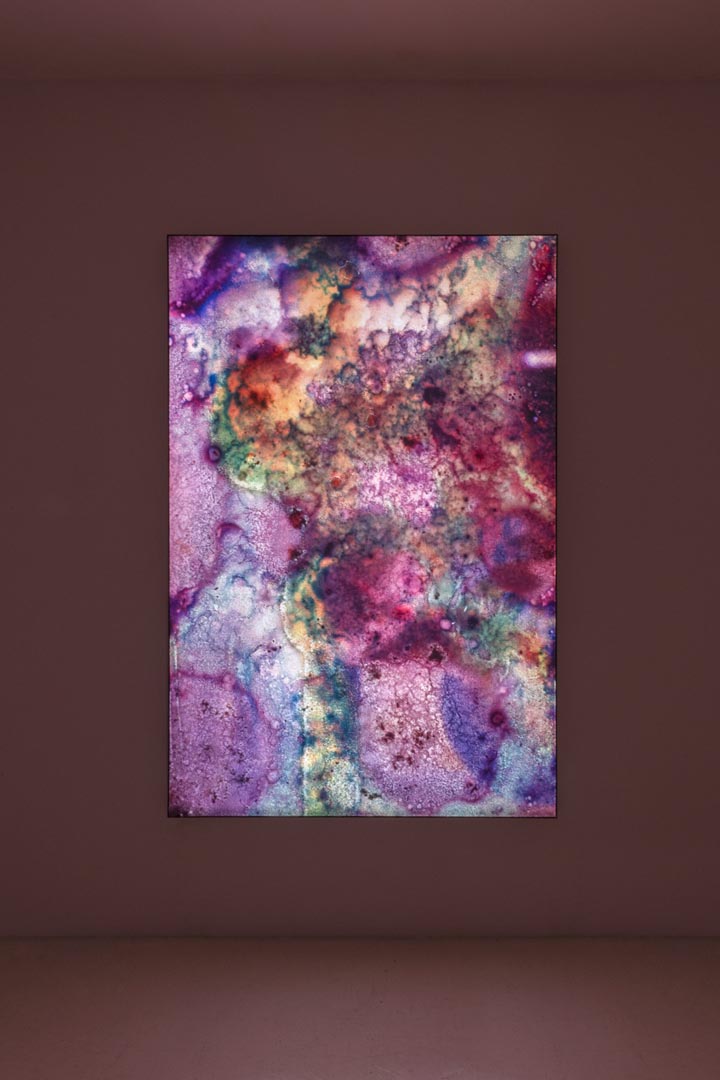

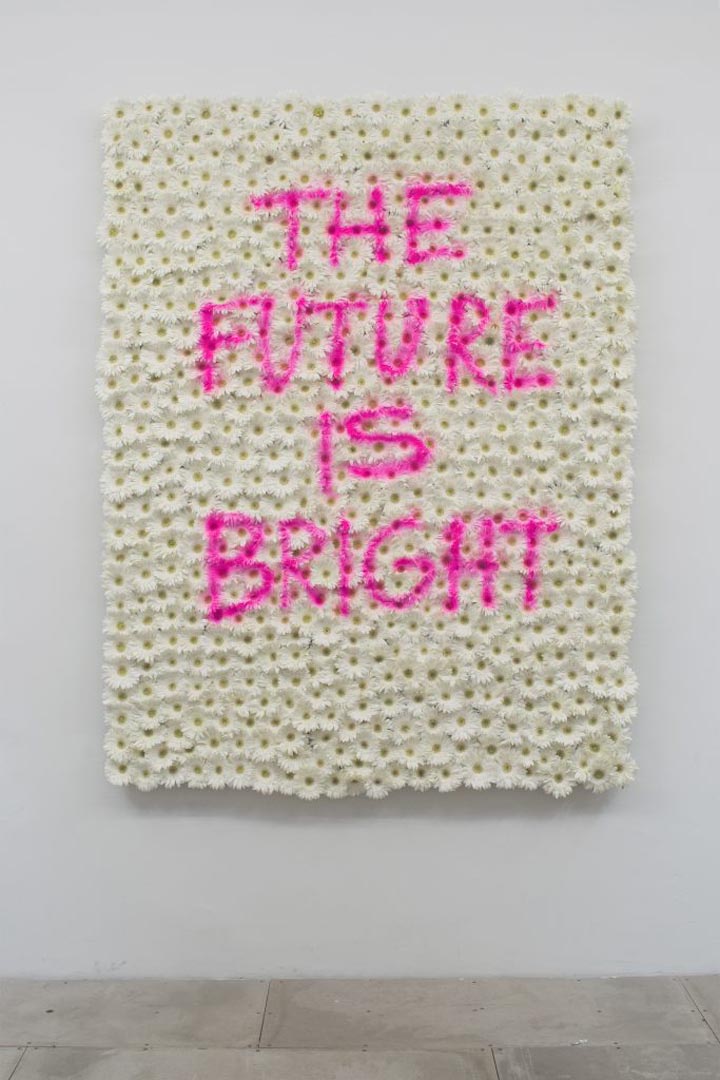

If you talk about time, you cannot but talk about death. In fact it too often appears in your works, especially in the form of memento mori, a theme as old as art itself. I am thinking of the fly on the alienating surfaces of LOSING CONTROL, a symbol of the ephemeral since the days of Baroque still lifes, or the delicate floral shrouds of I’m afraid I’m missing something, “pictorial evidence of the irreversibility of time”, or again THE FUTURE IS BRIGHT, with its slow decay that transforms the concept of the inscription. What does it mean to work with perishable material? And how much does this have to do with our contemporaneity and our analogue-digital life in which everything is at the same time ephemeral and immortal?

Everything is a “symbol of the ephemeral”: since everything is destined to end (or rather transform), everything is memento mori if you look at it from this perspective. This may sound pessimistic, but only because we have built our culture on the denial of death. We chase away the idea of it like we chase a fly away from a clean surface, knowing that the fly does not cease to exist if we do not see it. And so I believe we should accept the finiteness of our lives in order to fully appreciate their duration. Having said that, I realise how ironic it is to say this despite being an artist, who by definition does everything he can not to be forgotten and to survive through the centuries with his work; but it must also be said that today we all have the feeling that we can live forever through our online presence. It is a very complex topic to which I hope to add interesting insights, not least because the question of immortality is not so much about permanence but about the poignancy of what remains. And perhaps that is precisely why it does not matter whether the material of a work is perishable or “eternal”, what really matters is the content conveyed by the material.

Your works are strongly linked to physical space, not only in material terms but also in terms of substance. LOSING CONTROL, for example, with its dirty/clean dichotomy that refers to pandemic obsessions, but not only that, besides being a multisensory installation in which practically all human senses except taste come into play, it is an existential condition in which we exist, impossible, therefore, to simulate through new technologies. Moreover, yours is a complex installation in many respects, whereas in digital space, not only simplicity but also immediate fruition is preferred. What do you think about the relationship of art with digital space and new technologies? Can art, in the 21st century, still be contemplative?

I think it is a bit like questioning the legitimacy of using oil painting or bronze sculpture in contemporary art: as soon as an artist uses a medium or technique to express an idea, that becomes legitimate, then one can (and must) question one’s own taste and feeling towards the work. But above all, one needs a critical sense to analyse its content, since it is not the technique that legitimises a work but the combination of technique and content. Whether it is made of marble or pixels, therefore, matters little.

I certainly hope that my work is enjoyed more live than digitally, for obvious reasons of expressive choice. I believe that the superficiality with which most people approach works is exasperating: I often have the feeling that one does not linger on a work more than the time necessary to have a general view of it, a sort of scrolling of reality. The active public has turned into a passive spectator, and capturing its attention seems to have become a pervasive challenge. To have a contemplative audience, when often even those who write about art do not question what they see, seems utopian, yet every generative effort by artists is (and must be) aimed at a communication that passes through contemplation. I don’t believe that remaining on the surface to facilitate understanding of the work is the way to best reach the public, and, consequently, the digital space cannot be the only space in which the work and the public meet (unless that is what it was conceived for, of course).

In an interview, you advised young artists to do other jobs first, not because the artist is not a job, but because they train both humanly and technically. Quoting you: “Do other jobs both for the forma mentis and for practical experience because it can only help artistic research”. I would like to elaborate on that. I totally agree with you, in these terms, but I wonder: how deliberate is the choice to do other jobs, in many cases. How much these other jobs can become the only way to have an economic income, despite having at least five years of studies, a humanist but also a technical-practical education and numerous experiences of various kinds behind one’s back. How easy it can become to transform oneself, in a perpetual way, from an aspiring artist, who has studied and worked as hard as any other graduate, even sacrificing oneself economically, into a labourer, bricklayer, porter or any other job disconnected from the artistic sphere, jobs totally out of sync with an intellectual path, just because at some point you have to pay the rent. What do you think about that?

Let’s start with the assumption that if you are an artist, there is no moment when you stop being an artist. Even if you are sitting idle or doing physical labour you continue to think in creative terms. Secondly, as already mentioned, any work and any activity, no matter how totally disconnected it may appear from the intellectual sphere, will always be useful to those who hunger for creation. Today, the language of art is so broad as to embrace every aspect of life: one can create a work from one’s knowledge of plumbing or masonry, one can invent a new technique from a mixture of techniques belonging to fields far removed from art and from each other. There is no rule in artistic research, that’s the beauty of it.

As for the political issue of having to do a second job in order to be able to continue doing one’s own (or even just to survive), I think there would be too much to say to condense it into a concise answer, and I also fear that I do not have the means to structure here a valid indictment of the system in which we are immersed. In any case, I would like to say (hoping I am not making an apology for the aforementioned system) that being an artist is a constant act of faith: one has to believe in art and its power over the world every day, and on the other hand, one has to take on the responsibility that comes with it. No amount of hardship or humiliation, no criticism or recognition can change the spirit of someone who really wants to try to change things through art. Certainly, however, the faith and resilience of artists (and many operators) cannot and must not be an excuse to continue humiliating an entire sector. I hope that through solidarity between artists and the building of a real critical mass we can change this condition as soon as possible, until then we must continue to believe.

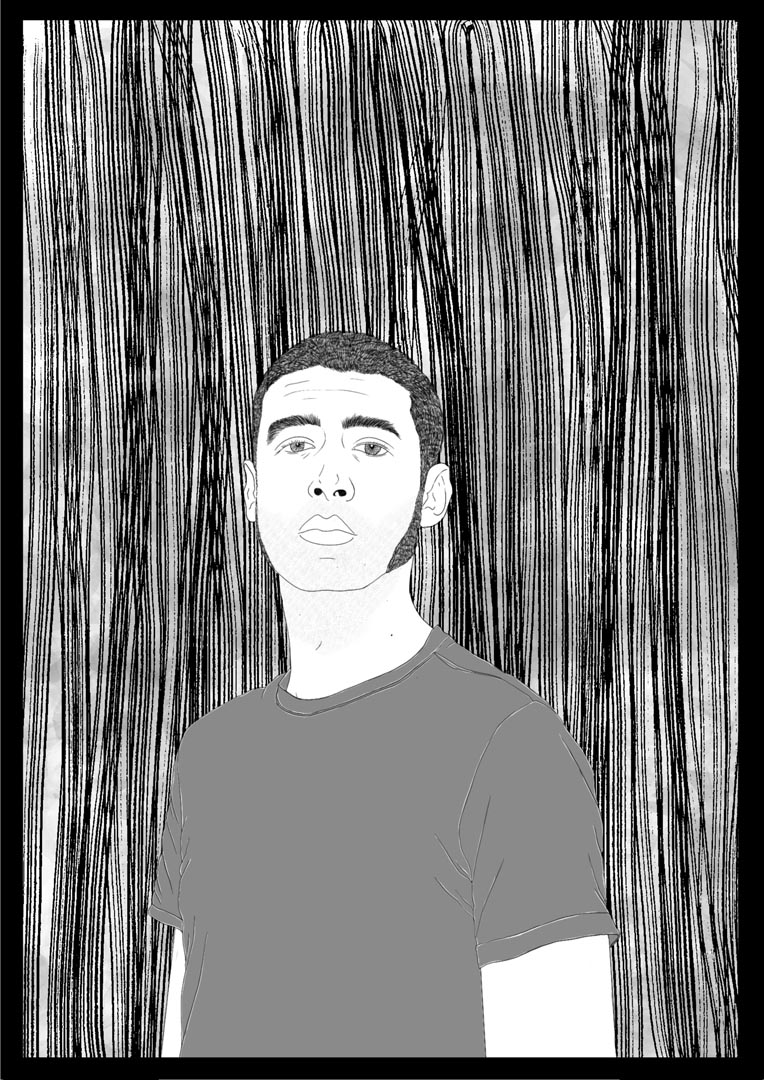

images (cover – 1) Giulio Bensasson, illustration by Nikla Cetra (2) Giulio Bensasson, «LOSING CONTROL», 2021, installation view, Pastificio Cerere Foundation (Rome), Ph. Carlo Romano (3) Giulio Bensasson, «Non so dove, non so quando», 2016, archive slide, #115, light-box, 225x150cm, installation view, Pastificio Cerere Foundation (Rome), Ph. Carlo Romano (4) Giulio Bensasson, THE FUTURE IS BRIGHT, 2020, Cut flowers, perforated sheet metal, spray paint (5) Giulio Bensasson, from the series «Non so dove, non so quando» (6) Giulio Bensasson, illustration by Nikla Cetra

“Survive the Art Cube” is a series of interviews with artists from different generations. The title borrows from Brian O’Doherty’s most famous book to echo its critical slant. It aims to better understand how these artists perceive the analogue-digital space in which we are immersed and our contemporaneity, what sense and importance artistic space has today and what sense it makes in our present to make an artistic journey. Dark times call for reflection on reality and only artists, perhaps, can open our minds.

Past interviews:

Interview to Eva Hide, Arshake, 28.12.2023

Interview to Federica Di Carlo, Arshake, 16.12.2023

Interview to Giuseppe Pietroniro, Arshake, 07.12.2023

Interview to Francesca Cornacchini, Arshake, 14.11.2023

Interview to Enrico Pulsoni, Arshake, 09.11.2023

Interview to Marinella Bettineschi, Arshake, 15.10.2023