The sixth interview for the series “Survive the Art Cube”, curated by Fabio Giagnacovo, is with Eva Hide (pseudonym of Leonardo Miscogiuri and Mario Suglia). An artistic duo (which becomes a trio with Eva, a multitude in their disguises) that in one way or another always presents us with a perturbing unconscious often filtered through digital iconology. Their work can in some ways be described as extreme, excessive, like a certain type of independent films revered by the niche, but just like those films, their works transcend shock to be seen in their dark, no-holds-barred essence. With them, we try to understand how to escape superficiality, what it means to work on such strong and exasperating themes and what role morality plays in Artworld.

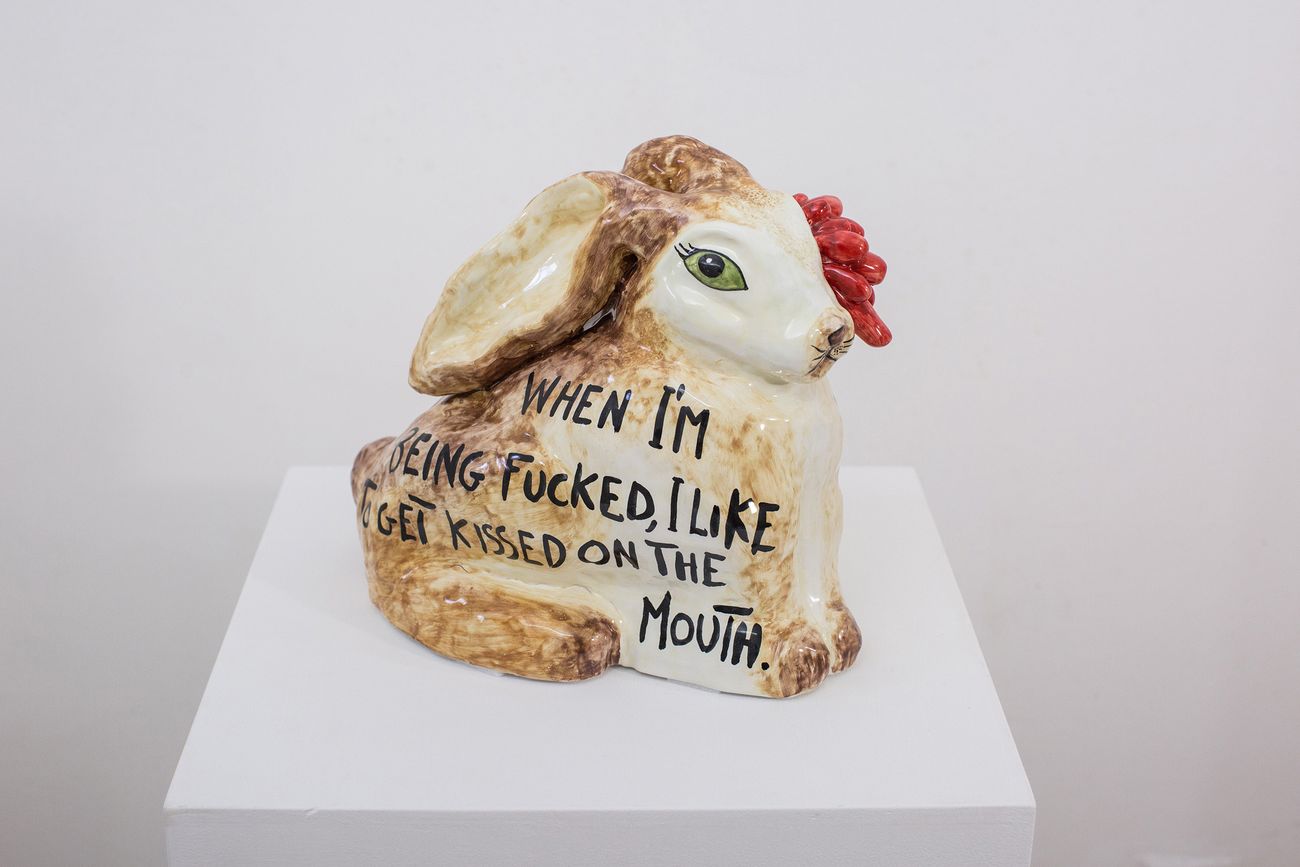

Fabio Giagnacovo: Your works are disorienting, often thanks to a mixture of everyday and childish elements in the midst of a horror, a disturbing unease. Sometimes it seems as if we are contemplating a situation of extreme discomfort filtered through the eyes of a child, others bring to mind the monstrous bodies of Bellmer’s dolls, others the dramatic majolica of Leoncillo. The objects you create always have a ‘weight’, never falling into the conceptual, but at the same time they are extremely ‘volatile’ in that existential malaise that catches us off guard, with that perversion in some cases extremely sharp, thrown in the face, essential. They are shocking works, one might say, but of a different kind from the soulless ones we are used to seeing around. How are they not banal? And, on the contrary, how do you manage to capture such absolute unease, of such dark purity as to be all-encompassing?

Eva Hide: Originality is inherent in the honesty and freedom of thought that artists adopt in bringing out their most sincere essence from their combination of ideas and skills, avoiding easy compromises with the trends of the moment. We believe that creativity is always combinatorial and lives from the ability to combine pre-existing elements into new solutions. The belief is that every idea is a remix that blends aspects of different ideas, perhaps even from different fields or different eras, into a new form.

Every insight carries with it a legacy of previous creations and nothing comes from nothing. The question is how willing we are to admit this. Our work would like to be a sincere and cruel mirror like Snow White’s, giving back an unfiltered image, closer to our primordial or beastly being if you like, but during the creative process, in a continuous weaving between playfulness and tragicity, the intentions are punctually disregarded because, always poised between reality and fiction, they are contaminated by anomalous visions that mingle with obscure Freudian obsessions, ambiguities of identity and memories of violence.

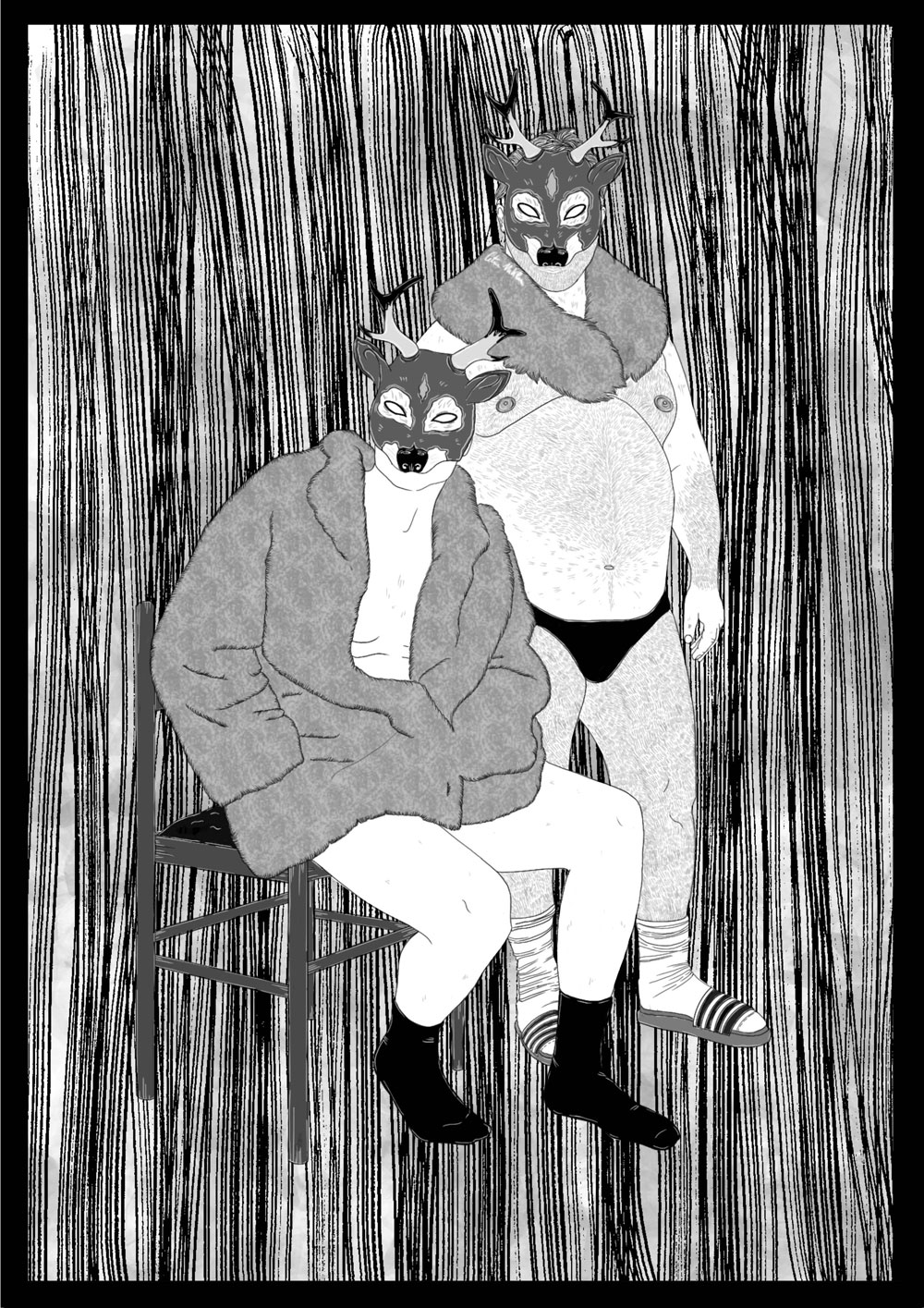

The way you present yourself and your work in the digital space has distinctly weird characteristics. I wouldn’t be surprised to see you coming out of the curtain of the Lynchian red room of the unconscious in Twin Peaks, next to the dancing dwarf who speaks in such an alienating way. What does it mean, for you, to be an artist? How much of yourself do you put into the artistic process and how do you relate to the fact that there are two of you signing the same work? Is there a mediation?

Eva Hide is a lie created to survive the ugliness of everyday life, which is far more absurd and cruel than what the poets tell us; we are children of an age that has realised that beauty will not save the world. Pathetic and painful as knowledge, ours is an art that does not believe in its healing power, but desperately attempts to shorten the height that separates us from the fall and to restore meaning to pain, restoring dignity to despair, transforming the wounds of being into poetry and finding life in death.

The work, although called upon to fulfil the knot between the objectivity of drives and the plasticity of forms, is not a deterministic effect of life, but is what retroactively rewrites it. We do not deny that there is a deep connection between our biography and the works, but we refuse to conceive the artistic process solely as the result of the course of our existence, of thirty years of love lived together, of vicissitudes, of mediations and games. The works transcend our intentions, becoming the places where the unconscious manifests itself and, resisting signification, appear alien to us.

Your universe of images is studded with cursed images, you use them, you exploit them to their full potential, and your works, too, somehow acquire all the characteristics of viral cursed images: in some works we glimpse them blatantly, others, I’m thinking of ceramic sculptures, lay the three-dimensional foundations, with sometimes, the addition of those writings of extreme disturbance, and even your painted majolica plates, so ‘everyday’ and elegant, leaving aside the rampant blackness that transports one into another dimension of thought, have in the image some disturbing element that condemns the observer to return, in the mind, to it, to “remember it forever”, to borrow the definition of cursed images. What role does the Internet play in your work? And what is that whole universe of disturbing, sometimes heinous, brazen, pornographic, unfiltered images, which in the fluid digital space has been able to spread extremely easily compared to a few decades ago?

We have always plundered from the internet at will, consolidating our restless imagination over time, giving us the opportunity to feel less isolated from what is happening in the world. At the same time, surfing the seas of the web, drawing bulimically from the images and information present, has generated in us a feeling that eludes the concrete and material perception of reality, a feeling of suspension, of indefiniteness, of incompleteness, a feeling to which we are unable to give body, to give meaning and to give a name; something that has to do with the consciousness of an elsewhere and that has condemned us to live a constant nostalgia for a place where we have never been, for a land unknown.

A feeling that nourishes and increases the doubts and uncertainties that lurk, like tormented spectres, in the narrow, dark spaces of the psyche.

Some commentators have called your artistic production ‘courageous’, as well as the galleries that exhibit it ‘courageous’. I believe that all art has to be courageous to be so, regardless of the themes it deals with, and I think that your artistic production is indeed courageous because it has an absolute destabilising charge within it, it does not stop at the taboo but somehow overcomes it, leaving us disarmed, unable to react to our unconscious that bounces between childhood, sexuality and death. In your opinion, what role does morality play in the artistic system? And is this heath of absolute freedom, as Artworld is sometimes presented to us, actually so?

Morality is always determined by the values that each epoch and society takes as the founding virtues of its civilisation and changes with them. The moral canons of art are those that the artist himself imprints on reality, even if these canons are not always socially shared, because they are subversive, disrespectful or simply, as in our case, inconvenient to respectable thinking. The current art system is a system in which everything and the opposite of everything applies, a regime characterised by the concentration of effective power in the hands of a minority, mostly working for its own benefit, often against the interests of others.

Artworld has become a proscenium in which we all perform like dolls in a shop window or monkeys in a zoo, in a glittering carousel that dazzles and seduces us with the glitter of things, the sirens of success, and that scarcely tolerates the freedom to dissent.

You are both of Apulian origin but have lived in London for a long time. Why this choice? And what do you think about the contemporary art scene for young artists? In my opinion it is a perturbing panorama, a bit like your works, playful and terrifying like Harmony Korine’s films, isn’t it?

The London experience unfortunately came to an end because our artistic research required spaces and equipment that were not compatible with the economic possibilities we had, so we returned to Apulia to re-equip a studio and pursue our project. The reason that had prompted us to migrate was the need to emancipate ourselves from the stagnant and marginal condition in which contemporary art in Italy finds itself, and to live in a context in which art expresses the complexity of the world, enjoys great vitality and maintains a prominent role in the cultural and economic fabric of the country.

In Italy, there are many young artists, some talented and promising, who are often swallowed up by the art system of small and medium-sized Italian galleries that, adopting the rules dictated by marketing, act along the lines of the formats of famous television talent shows, with the sole purpose of extracting the greatest profit from their work in the shortest possible time. The result is to stifle creativity and its possible developments to the advantage of a repetitive and reassuring production because it is already accepted by the market.

Accomplice to this sterile and asphyxiated propensity, with very few exceptions, is the undergrowth of the critical and curatorial apparatus of the art system which, instead of creating opportunities for comparisons and analyses useful for stimulating growth, has practically reduced its fundamental role to that of submissive lackeys in the pay of the highest bidder.

images (cover – 1) Eva Hide, illustration by Nikla Cetra (2) Eva Hide, «My dad loves me», 2017, painted majolica and children’s underwear, environmental dimensions (3) Eva Hide, «Rabbit», 2019, painted majolica (4) Eva Hide, Kammerspiel exhibition at ADA Gallery, Rome (5) Eva Hide, «Playground», 2018, painted majolica (6) Eva Hide, exhibition view ArtVerona 2017 (7) Eva Hide, illustration by Nikla Cetra.

“Survive the Art Cube” is a series of interviews with artists from different generations. The title borrows from Brian O’Doherty’s most famous book to echo its critical slant. It aims to better understand how these artists perceive the analogue-digital space in which we are immersed and our contemporaneity, what sense and importance artistic space has today and what sense it makes in our present to make an artistic journey. Dark times call for reflection on reality and only artists, perhaps, can open our minds.

Past interviews:

Intervista Federica Di Carlo, Arshake, 16.12.2023

Intervista Giuseppe Pietroniro, Arshake, 07.12.2023

Intervista a Francesca Cornacchini, Arshake, 14.11.2023

Intervista ad Enrico Pulsoni, Arshake, 09.11.2023

Intervista a Marinella Bettineschi, Arshake, 15.10.2023

Intervista a Federica Di Carlo, Arshake, 16.12.2023