The research by Kisito Assangni on “curating as a phenomenological history of everyday life”, continues today in dialogue with Dr. Matthew Bowman (University of Suffolk, UK).

Kisito Assangni: How can museums and universities be used as pedagogical tools in a public sphere characterised by heightened intolerance?

Matthew Bowman: The situation in the United Kingdom is very concerning at the moment—admittedly, it often is—insofar as the Conservative Party has been engaged in stoking a culture war in order to secure its power base through a politics of binarizing division. Once again, art, and culture more broadly, faces itself confronted on various fronts. Oliver Dowden, the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, has intervened upon membership boards of museums, threatened funding avenues, and sought to promote a history of English society in which all inequalities are somewhere between mirage and ideological delusion, hence of no reality in the Tory mindset; whilst Gavin Williamson, an education secretary perennially muddled over the distinction between education and training, while being largely incapable of benefitting either, has routinely tried to downgrade arts and humanities at all levels of pedagogical endeavour in favour of the so-called STEM subjects. This classic pincer move, a veritable rear-guard action, has come at a time when a reenergized civil rights movement has emerged internationally to contest racial discrimination, wilful climate destruction, continued gender and sexual inequality.

Because of the proximity between cultural institutions, governmental largesse, and corporate sponsorship within the public sphere, there is a real challenge thrust upon museums and universities. In essence, the funding which they depend upon for their continued existence is very much at risk, and the situation is further worsened by the ongoing consequences of Brexit. This suggests, then, that whatever value museums and galleries as pedagogical tools might have is presently at tremendous risk. But negatively, it also underscores that those institutions do possess an appreciable value: to want to diminish them, intercede on their policies, redirect their exhibition making—all these testify to the pedagogical strength of museums/galleries. If the right truly believed that such institutions held little or no value, then they could almost be left alone. Nobody believes in the power of art quite as much as the iconoclast, to that extent.

It is sometimes believed that art flourishes in difficult times. The belief is perhaps exaggerated and can be overly deterministic, but museums/galleries cannot retreat in the face of a culture war and, perhaps, even need to use that war as its fuel. Easier said than done, to be sure. But it is something art is good at and if such art is not supported by mainstream museums/galleries, then alternative institutions will need to step in.

What are the subjective and objective elements that make cooperative curating meaningful and valuable?

There is a risk that I am going to (mis)read the terms “subjective” and objective” in my response, but hopefully in a way that is justified and productive. Let’s take “subjective” as not connoting the personal, but instead in terms of the subjectivities that are manifested and produced by exhibitions.

In the last few months, I’ve noticed that Immanuel Kant’s aesthetics is a recurring presence in my writing. What, though, does he offer in 2021? Part of my interest here is that his aesthetics does not proffer anything resembling a primer for judging artworks (as good, bad, beautiful, ugly, critical—whatever), but rather constructs an account elucidating the intersubjective grounds of judgment. For Kant, there are no rules governing beauty, nothing that allows us to see that artwork as placeable in a pre-existing box labelled “beautiful artworks; but the act of judgment is not an expression of personal aesthetic preference, for all that. Our judgments are not voiced as a statement of personal likes/dislikes, Kant argues, nor are they made as applications of a rule; rather, they are voiced as if they would determine the rule and only count in the moment of voicing. Because they are “voiced,” the judge discovers whether his judgment speaks for others—conforms to their experience—and thereby also discovers whether a community of shared interests exists or not.

The generation or two of thinkers following in Kant’s wake would tackle the consequences of his account of aesthetics. Although Hegel might not quite perceive himself as extending Kant’s aesthetics, it is nonetheless plausible to contend that Hegel’s comprehension of subjectivity and experience not as something pregiven and immediate, but as only truly occurring through and as articulation in an ultimately intersubjective network, is a revision of Kant. Said slightly otherwise, the voicing of aesthetic judgments are the actualization of subjectivity; prior to that voicing, there was no subjectivity as such, or, to say the least, a subjectivity differently constituted.

By the same token—and much more briefly—let’s take “objective” not as neutral, disinterested, or impersonal, but instead as naming the specific relationship to the art object. That art “object” conditions our affective responses and judgments, it is the occasion for our gathering together and for reflection. The “object” precedes the judgment. In that case, exhibitions as displays of or occasions for artworks can be said to be spaces in which subjectivities are instituted or remade; in them we discover what kind of community we are—even if only temporarily as each exhibition compels a new judgment, and hence institute a new actualization of subjectivity. The hope is that community is different from the alienated mass, such as the agglomeration of individuals on social media. It is hopefully, too, a space where we discover being-with and co-presence, what we share in and through difference, rather than utter separation and individuation.

How do curatorial strategies inform cultural institutions in contemporary society and what sort of critical and transformative potentials can be traced in exhibition cultures?

For quite some time now, I have been interested in the idea that what has been designated the “public sphere” found its early formative articulation in and around the experience of the salons in Paris, especially during the course of the eighteenth century. Writers like Denis Diderot were explicitly seeking to both speak to and assist in establishing that public through the production of art criticism. That is to say, we might imagine that art criticism sought to acknowledge, and perhaps even activate, a semi-amorphous public sphere that was coalescing around art exhibitions. Of course, it might be objected that despite whatever democratic aspirations Diderot might have clung onto, the public sphere he dreamed remained highly stratified. The French Revolution opened the salons more fully and one can perceive revisions and radicalizations of Diderot’s project in Charles Baudelaire’s review of the 1846 salon (albeit, Baudelaire’s version, perhaps with deliberate irony, engorges itself upon tyranny via its dedication to the bourgeoise).

Since those heady times there has been an off-on belief in a positive relation between a public sphere and exhibitions. Scepticism on these matters is perhaps justified as any attempts to create a more genuinely inclusive and social democratic public sphere cannot be forced upon art alone. Yet it is worth grasping onto the belief that artworks can instantiate alternative forms of experience beyond those mandated by the disciplinary apparatus of capitalism, and such works are first and foremost are experienced in the actuality of an exhibition context. The history of art is often, in great measure, the history of artworks in exhibition; the claims we impute towards art cannot be detached from exhibitionary structures. On that score, Institutional Critique is clearly less a rejection of such structures—the museum, for example—but rather amounts to a belief that those structures can perform a positive and vital task if they are put to good and reflexive use.

Does an exhibition count as philosophy, anthropology, sociology, etc.? How does this mode of presenting ideas compare to an essay or other more traditional academic outputs?

I have conflicted views on the first question. There have been occasions where I felt that artworks themselves are not philosophy but that they may exert philosophical effects and open themselves to philosophical questioning. Those occasions have typically been while speaking with professional philosophers, especially those engaged or interested in art in some respect. My denial concerning art-as-philosophy is partly to maintain a kind of space between art and philosophy whereby each can render truth claims according to their particular mediums and contexts; partly to prevent art being transformed into philosophy’s self-image; and partly to shield art from expectations that meets established protocols of philosophical argument and truth which may result in specific artworks being lambasted as being bad philosophy or philosophically ridiculous. Underpinning all this is a longstanding shared history between art and philosophy that was opened by Plato’s remarkable arguments in his The Republic. That history has had many twists and turns, and, in more recent times, has generated a bifurcation between philosophy (whether analytic or continental) and what has been loosely termed “theory.”

And yet, in contending that artworks “exert philosophical effects” and “open themselves to philosophical questioning,” might not one just simply remark that artworks are another way of doing philosophy? Here is where my own personal intellectual conflicts emerge, but perhaps it makes sense to claim that artworks are not philosophy but ways of “doing philosophy.” In a more Heideggerean fashion—or, at least where Heidegger rubs against Hegel to produce the varieties of discourse typically referred to as post-structuralist—we might say that that artwork practice “thinking” rather than “philosophy” per se. For this reason, unknowing can be a legitimate telos of an artwork, and one that does surrender art to the merely irrational or ineffable.

Undoubtedly, my response has drifted away from your question, so I will try to swing back to it. The question was about exhibitions, rather than artworks as such, and stretched beyond philosophy. Essentially, the overall tenor of my response would be more or less the same, with minor modifications. Exhibitions, too, “exert philosophical effects” without being reducible to philosophy—the rules of engagement are different. Matters are perhaps otherwise when it comes to, say, anthropology, whereby its accumulation and study of material artefacts and customs has historically gone hand-in-hand with modes of display. Indeed, while there are numerous museums and exhibitions of anthropology/ethnography internationally, it is hard to imagine a corresponding situation for philosophy or sociology. That is far from claiming that exhibitions do not or cannot engage in these things: on the contrary, exhibitions can be about, in one way or another, philosophy and sociology—they may deconstruct these fields of knowledge production.

In a world of post-truth politics, how can art speak to the problem of the real, truth and facticity from inside a disciplinary practice?

Offering a “how” as such is probably far more difficult than imagining what conditions must be in place in order to conceive notions of truth, real, and facticity. And it might be worthwhile following the philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer—himself extending Martin Heidegger’s contribution to phenomenology—in counterposing truth to method (the latter constituting a “how” or “how to” as an description of hermeneutics. And, of course, how we define “truth” philosophically is likewise extremely difficult and open to debate—does it involve “correspondence”? Or, since Heidegger was just mentioned, “aletheia”?

Art has long questioned any easy conception of truth and this where matters become extra fascinating and sticky. Take, for example, the famous photomontages of John Heartfield, such as the ones in A.I.Z around 1932 that aim to forestall Hitler’s ascension to power. A photomontage such as Hitler the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk presents an image of Hitler with his torso X-rayed, thereby revealing a vertical chain of German money reaching from his stomach upwards. The image is “fake,” of course, as it has been composited from various elements. Though the image has indexical elements, the manner in which those elements have been arranged together entails rejecting any direct connection between indexicality and truthfulness or documentary value. But this does not mean we should disregard Heartfield’s photomontage as a prewar example of post-truth propagandizing. Instead, the photomontage purposely exploits the indexicality of straight photography in order to stress its supposedly natural link to truth. Moreover, it, in a Brechtian manner, suspects that truth cannot be established by straight, apparently unmediated, photographic transcription, that the interplay of heterogeneous fragments constructed together is what is required. Put differently, it suggests that fiction, even premised upon unreality and imagined situations, does not exist in opposition to truth.

Several decades have lapsed since this avant-garde strategy was first implement in the years following World War One. But it is a strategy that has been much repeated and reinvented in the interim within various neo-avant-gardes, postmodern genres, and in contemporary art. For example, we can see more than its mere vestiges in artists such as Hito Steyerl as a means for interrogating the truth constructions in twenty-first century media culture.

What makes this “sticky” is that it may serve as a potential defense of “post-truth” in a roundabout way. Seemingly, many rightwing figures bemoaning what they take to be postmodernism’s demolition of absolute truth and replacing it with a multitude of perspectives are also happy to defend such notions of post-truth. Yet I would argue against any collapse here between, on the one hand, the ways avant-garde art and the lessons of postmodernism, and, on the other hand, post-truth ideologies. The former enact a link between form and content: a self-aware fictitious form is utilized to posit contents that convey and examine truth. Truth is tested rather than asserted. Post-truth is less beholden to the truth-content of its form; instead, its form is merely catchy, shareable in a social media universe, and extrinsic to whatever its content might be.

How does the recent mass movement of people change the curation of the future?

This is a delightfully ambiguous question, so allow me to play on that ambiguity a little! If the question is about future curatorial approaches or concerns (which is how I first read it), then I would say that, historically, curating emerges from the rise of the museums during the Enlightenment and the nineteenth century. Coincident with, and concomitant upon, the virtually simultaneous rise of the nation state, museums were spaces within the public sphere in which collective identity can be manifested and perhaps even interrogated.

Any book or exhibition recommendations?

Not an exhibition as such, but I heartily recommend Jes Fernie’s Archive of Destruction website. The Jean Dubuffet exhibition at the Barbican is wonderfully generous presentation of his career. Book-wise, these questions remind that I need to come back to reading Hal Foster’s What Happens After Farce? But I am also heartily enjoying Darby English’s various books, too, particularly his 1971: A Year in the Life of Color.

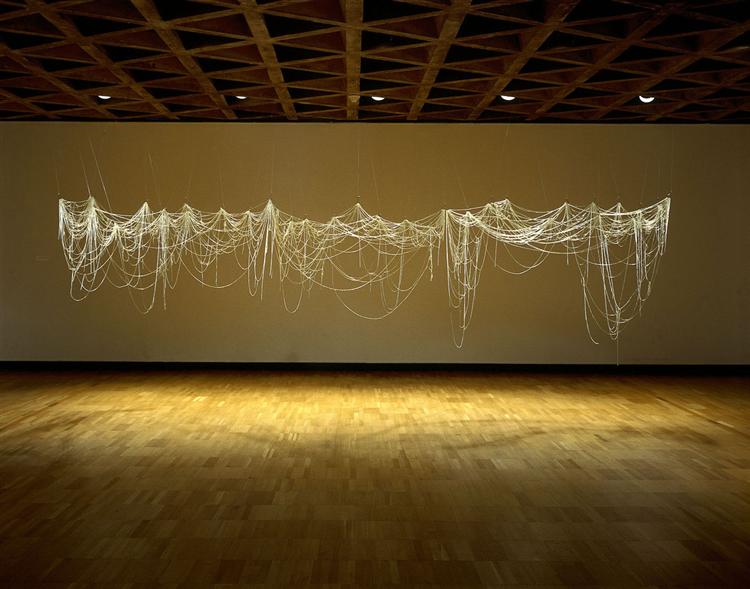

images: (cover 1) Roni Horn, «Untitled (I deeply perceive that the infinity of matter is no dream)», 2014 (2) Eva Hesse,«Right After», 1969 (3) André Valensi, «Pièges à regard…»,1990 (4) Theaster Gates,«Raising Goliath», 2012 (5) Hannah Stageman, «Untitled (Stour Woods)», 2013

Dr Matthew Bowman is a widely-published art critic, theorist, curator, and historian who obtained his doctorate at the University of Essex with a dissertation on the October journal and its rethinking of medium specificity.

He lectures in fine art at the University of Suffolk and regularly writes art criticism for Art Monthly. His research focuses on twentieth-century and contemporary art, criticism, and philosophy in the U.S. and Europe. He has authored numerous essays. In 2018, he published “Indiscernibly Bad: The Problem of Bad Art/Good Painting” in Oxford Art Journal and in 2019 “The Intertwining—Damisch, Bois, and October’s Rethinking of Painting.” His essay, “Art Criticism in the Contracted Field” is included in the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism in 2021 and this year he has published an essay on Douglas Crimp titled “The Haunting of a Modernism Conceived Differently” in InVisible Culture. Currently, he is finishing editing an essay collection to be published as The Price of Everything and the Value of Nothing: Art Criticism and the Art Market for Bloomsbury and October and the Expanded Field of Art and Criticism for Routledge. Some of his writings can be found here: https://ucs.academia.edu/MatthewBowman

The interview to Dr Matthew Bowman is part of Kisito Assangni’s research on “curating as a phenomenological history of everyday life”:

Transitory conversations with reputable curators who engage positively with artistic practices driven by non-oppressive facilitation, alternative pedagogies, chronopolitics, and contemporary urgencies within the context of larger political, cultural, and economic processes. At this very moment in history, as well as raising some epistemological questions about redefining what is essential, this revelatory interview series attempts to bring together different critical approaches regarding international knowledge transfer, transcultural and transdisciplinary curatorial discourse. (Kisito Assangni)

Past interviews:

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Nadia Ismail (Arshake, 23.03.2022)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Mario Casanova (Arshake, 14.01.2022)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Nkule Mabaso (Arshake, 09.11.2021)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Lorella Scacco (Arshake, 20.07.2021)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Kantuta Quirós & Aliocha Imhoff (Arshake, 11.05.2021)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Adonay Bermúdez. Universal Truths Have no Place in Curating (Arshake, 08.06.2021)

Kisito Assangni, Kantuta Quirós & Aliocha Imhoff. Curatorial Methology as inter-epistemic dialogue (Arshake, 11.05.2021)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Adonay Bermúdez. Universal Truths Have no Place in Curating (Arshake, 08.06.2021)

images: (cover 1) Roni Horn, «Untitled (I deeply perceive that the infinity of matter is no dream)», 2014 (2) Eva Hesse,«Right After», 1969 (3) André Valensi, «Pièges à regard…»,1990 (4) Theaster Gates,«Raising Goliath», 2012 (5) Hannah Stageman, «Untitled (Stour Woods)», 2013