The research by Kisito Assangni on “curating as a phenomenological history of everyday life”, continues today in dialogue with art critic David Frohnapfel, discussing about the possibilities of “radical reformulation of relationality and intersectional solidarities.

Kisito Assangni: How can curatorial platforms re-articulate knowledge in the context of our turbulent geopolitical climate?

David Frohnapfel: In the last couple of weeks, I have this strong desire to go back to Michael Jackson’s pop music catalogue of the 1990s and watch his music videos. There is something rather naïve but beautiful about the idea that we must all just get along, hold hands, and sing the lyrics of his 1995 released Earth Song to summon a force that can heal the world for us. Unfortunately, it seems still an uncomfortable truth to articulate that we are not all in this together on equal terms. Racialized and classed groups continue to carry the weight of structural inequalities disproportionately. How can we arrive at a new and better “we” when necropolitics (Achille Mbembe 2019)—the difference between what is considered valuable, savable, and grievable life (Judith Butler 2010) and what is devalued, dehumanized, and seen as expendable—is still such an omnipresent truth that structures societies at large? Like many of us, I’m stuck with the question in my work, why there’s so much protection, support, care, and love missing for so many groups of people?

I think curatorial platforms must continue the work to unsettle and destabilize power relations, speak directly to and with Civil Rights struggles of marginalized communities, and strive for better forms of solidarity beyond mere performative gestures of goodness and togetherness. Simply put, rearticulating curatorial knowledge means to me to engage with the question how we as curators, scholars, and artists can become part of the process to put more pressure onto oppressive structures? How can we find better ways to think through and make transparent the multiple complicities that knowledge productions of all kinds—curatorial, academic, artistic, activist, archival, and others—sustain with structures of oppression? I believe very much in the idea that, “[i]f we start with complicity, we recognize our proximity to the problems we are addressing” (Fiona Probyn-Ramsay cited in Sara Ahmed 2012). Many intersectional queer-feminist and trans* writers of color have shown us that epistemic systems are not innocent but shaped by various structural forms of oppression due to settler colonial continuities, racial capitalism, cis-heteropatriarchy, ableism, class oppression, and nationalism.

Hence, from my perspective, I think the study of art and exhibition making has to shift in a more explicit manner from the interest in aesthetic formations towards histories of hegemonic power relations. What are the epistemologies we can develop to actively weaponize art in such a fashion that it becomes a transformative process of shifting existing relations of power beyond performative gestures for (utopian) change? And how do the epistemologies we have already developed to make better sense of art and its histories continue to be influenced by the unacknowledged whiteness of the discipline’s past and present?

What strategies do you believe art institutions should be fostering to increase visibility within their ranks?

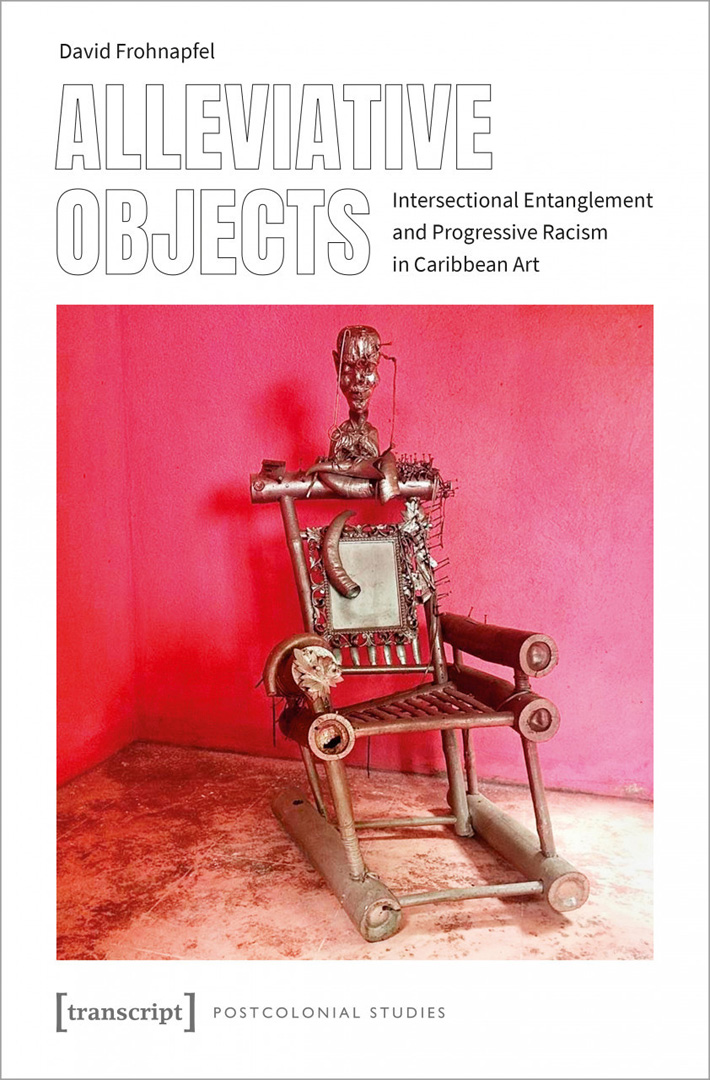

Art historian Krista Thompson, following Peggy Phelan, pointed out that we need to start interrogating the implicit assumptions about the connection between representational visibility and political power and the “limited effectiveness of strategies of visibility” (Thompson 2015: 39). In a state of hypervisibility, racialized, sexual and gender minorities often remain in situations of social, economic, and intellectual marginality. I have discussed in my book Alleviative Objects (2021) how the members of the Caribbean art collective Atis Rezistans are a concrete example for such an unfortunate process: they are hyper-visible in the discourse of contemporary Haitian art and seemingly ‘inside’, but they remain at the same time ‘outside’ the established art system. I retraced how, ironically, it is the repetitive narrative of generous inclusion by many white institutions and actors that fixes Haitian artists in a constant state of “re-institutionalization” and “re-discovery”; this fixation is a circular motion which fails to lay bare structures of (progressive) racism that underlie the conditional hospitality (Sara Ahmed 2012) of many art institutions. It is a way of performing white progressiveness and reestablishing discursive power rather than developing new substantial tools of undoing structural mechanisms of racialized, classed, and gendered forms of inequality deeply engrained in most institutional formations.

Michel-Rolph Trouillot analyzes in his book Silencing the Past. Power and the Production of History (1997) how historiography is a hegemonic process that creates more silences. I’m intrigued by Trouillot’s writing and how he subverts the common assumption that historians, curators, and their memory institutions unveil buried aspects of the past and make them more visible. Instead, he centers the idea that historians are complicit in producing silences through their archival and counter-archival work that might end up muting people’s experiences. The brightest spotlight may indeed cast the largest shadow. I propose to read Trouillot’s concept of silencing together with Mari Matsuda’s important idea for an intersectional critique that asks scholars to always work in coalition and “ask the other question”. She describes: “The way I try to understand the interconnection of all forms of subordination is through a method I call ‘ask the other question.’ When I see something that looks racist, I ask, ‘Where is the patriarchy in this?’ When I see something that looks sexist, I ask, ‘Where is the heterosexism in this?’ When I see something that looks homophobic, I ask, ‘Where are the class interests in this?’ Working in coalition forces us to look for both the obvious and non-obvious relationships of domination, helping us to realize that no form of subordination ever stands alone.” (1991)

Reading Trouillot’s and Matsuda’s theories back-to-back also offers me a framework for doing curatorial work because it helps me to stay alert to how privileges and marginalities operate in intersectionally entangled terms that never stand alone. Art institution should foster working environments for coalitions with expertise for anti-racist, queer-feminist, trans*affirming, and anti-capitalist knowledges, which can bring various and sometimes conflicting grammas to speak about inequality at the same table.

How can curatorial methodologies promote experiences that go beyond visuality?

As someone who works in the field of contemporary art, I think curatorial methodologies should follow artists and their artistic practices and not the other way around. I don’t think that the “visual” is per se the most crucial or dominant aspect for many artists working today. Many artists shift their artistic practices constantly between very different media and interdisciplinary practices. To me, the process of fetishizing visuality and material objects often comes from a “display logic” implemented by museums, exhibition spaces, and market demands. I’m quite skeptical that exhibition making is the best or only form to engage with the medium art. Many exhibitions continue to prioritize material art forms (installation, painting, sculpture, photography, video) over more ephemeral, elusive, performative, conceptual, experiential, digital, socially-engaged, or text-based ones.

Although I have done a lot of work evaluating socially-engaged art from a critical standpoint in my published work, I am influenced by the idea that art can indeed become a productive tool for creating new communities and relationships. Curator and art critic Nato Thompson adroitly explains in his book Seeing Power (2015) that one of the most challenging aspects of socially-engaged artists’ work is indeed to see and understand complex infrastructures of power within communities. Whatever the intention, there are no relationships without power dynamics.

What curatorial and artistic propositions for alternative social and environmental bonds need nourishing?

My working definition of ‘queer’ is derived less from sexual deviance and rooted instead in forms of communal potentiality that explores broader alliances and systems of kinship between very different groups of people. I think the intellectual trajectory of queer communal thought of scholars like Leela Ghandi (2006), the Combahee River Collective (1977), Audre Lorde (2007), Ann Cvetkovich (2013), Jennifer C. Nash (2013), José Esteban Muñoz (1999), Michel Foucault (1982), among others, opens an interesting debate to answer your question. The unsettling power of queer resistance arises, according to Michel Foucault, “from the prospect that gays will create as yet unforeseen kinds of relationships that any people will not tolerate” and from “new life-styles not resembling those that have been institutionalized” (O’Higgins 1982: 22). I’m fascinated by art projects that aspire in a similar fashion to the creation of new sites for a radical reformulation of relationality and intersectional solidarities outside common social contracts.

I often come back to Walter Mignolo’s (2011) important claim that we must change the terms of conversation not just the content. Many museums are comfortably staying on the “content level” by appropriating critical knowledge through their programing without investing a lot of labor and resources in the important political work to implement structural change or improve the infrastructure for often precariously hired staff. Using the language of diversity often does not translate into more equal environments. The performative claim for institutional betterment seems to be a central paradox of our times and it needs better investments that will inspire systematic change. It is not enough to articulate that we are living in an unjust racist system, but museums and universities also must mobilize labor and resources to engage with political activism, programs, and projects around reparative justice for QTBIPoC communities. Equity and understanding cannot be achieved passively without the active labor of seeking out ways of dismantling and undoing the status quo. I think it is fantastic that museums increase their pedagogical conversations about the restitution of looted objects, for example, but they also should ground their work fundamentally around the larger project of reparative justice and the radical redistribution of wealth, resources, and power.

How might curatorial practices look in the future?

Let me answer your question with a swift detour: I recently began an exhibition project with an episode I came to understand as embedded in cis-heterosexist ignorance. I was hired to bring a queering perspective to an already developed exhibition proposal. I started the first group meeting with a request to create a safe(r) environment for LGBTQI+ artists because conversations about queer forms of relating to this world, scholarship, and people can still charge a room rather quickly; in particular those environments that haven’t done any work yet of acknowledging complicities institutions sustain with cisheteropatriarchal power dynamics that symbolically annihilated queers from history. My question for a safer environment for queers caused one of my co-curators to loudly accuse me of “being discriminating against white, straight [cis-gendered] people” and that she and her museum work for “everybody”. I don’t think it needs a lot of sociological finesse to analyze and understand where her dramatic posture of defensiveness came from: she felt uncomfortable by seeing aspects of her identity marked which are historically unmarked, invisible, and hence often understood as universal. In this case: Being white, cis-gendered, and straight. Needless to say, her emotional response made it impossible for me in return to establish any feelings of belonging to this museum. Asking for a safer and more accommodating environment can indeed already be the starting point to experience more institutionalized violence.

On a very simple and straight forward level, I want to see a future for curation where those unnecessary situations of ignorance and conflict will not be the time- and energy-consuming starting point for our conversations about equity for sexual, gender, and racialized minorities, which risk recentering majoritarian perspectives and feelings. For so many people who are living in LGBTQI+ bodies and face multiple correlated forms of oppression finding spaces for comfort and belonging remains rare. Audre Lorde has famously described a permanent drain of energy faced by minorities and women when they are forced into a position to explain and teach their experiences to more privileged social groups—groups which still refuse accountability for their own actions and for decolonizing their hearts, minds, and institutional realities. Lorde argues that the energy lost on explaining and rendering one’s own position intelligible to a majority can find better use in redefining oneself and devising realistic scenarios for altering the present and constructing the future.

Queer-feminist scholars have retraced how the incapacity or refusal to “feel at home” and “inhabit” heteronormative principles constitutes people as queer and thus as threatening, pathological, impossible, unproductive, or immoral. I imagine curatorial spaces in the future that can take place in more accommodating working environments where defensiveness and fragility will not be the starting point to speak about minority knowledges. Hopefully, anti-racist, queer-feminist, and intersectional knowledges will be at the heart of our curatorial debates. I very much concur with many artists working in socially-engaged fields that community-building might be a central means for healing and surviving aggressive white, hetero-patriarchal, cis-gendered, and able-bodied environments and for resisting the drain of energy described above. So, I would say that curatorial practices in the future might continue to go in the direction of politized practices of “community care” centered in intersectional critiques.

Sadly, I do not believe in a progressive linear understanding for change. Many curators, scholars, and activists will cling to their privileges and desperately try to recenter majoritarian frameworks. Sara Ahmed (2017) has conceptualized privileges adroitly in her writings as an energy saving device wherein less effort is required to pass through the world when it has been assembled around and for you. Curatorial platforms might become environments where we discuss how we can assemble new worlds, which accommodate all kinds of bodies that often fall outside the norms given by institutional requirements.

In brief, museums, universities, and other memory institutions should start taking responsibility not primarily for objects but also for human beings. Becoming more aware about histories of resistance of marginalized groups is probably always a good starting point to think about the future.

Any book or exhibition recommendations?

One of the most impressive books I have read in the last years was Jennifer C. Nash’s Black Feminism Reimagined. After Intersectionality (2019). The book asks the crucial question who owns intersectionality? Now that the term enters more and more into mainstream debates and public awareness as a tool for analyzing the interconnectedness of all forms of oppression, I think Nash’s work is a very helpful inquiry and starting point for navigating what is happening to a Black lesbian anti-capitalist program when it becomes institutionalized throughout various disciplinary formations in the university, whether Women’s Studies or Black Studies’ programs. The book also speaks about how the figure of Black woman is often called upon to perform intellectual, political, and affective “service work” and to vouch for how certain (white) university departments have overcome its pasts exclusions. Nash argues that Black feminisms are autonomous intellectual traditions that offer a sense of “collective world-making” and are more than an anti-racist intervention that corrects white shortcomings. There is still a lot of catching up to do though in German-speaking academia—and art history departments in particular—when it comes to taking race as an analytical category seriously.

In February, I saw what I believe was the first large retrospective of visual activist Zanele Muholi’s photographic work at Gropius Bau in Berlin. The exhibition was a great way to understand how necessary it is to see the default position of ‘straight cis-ness’ as outdated and obsolete.

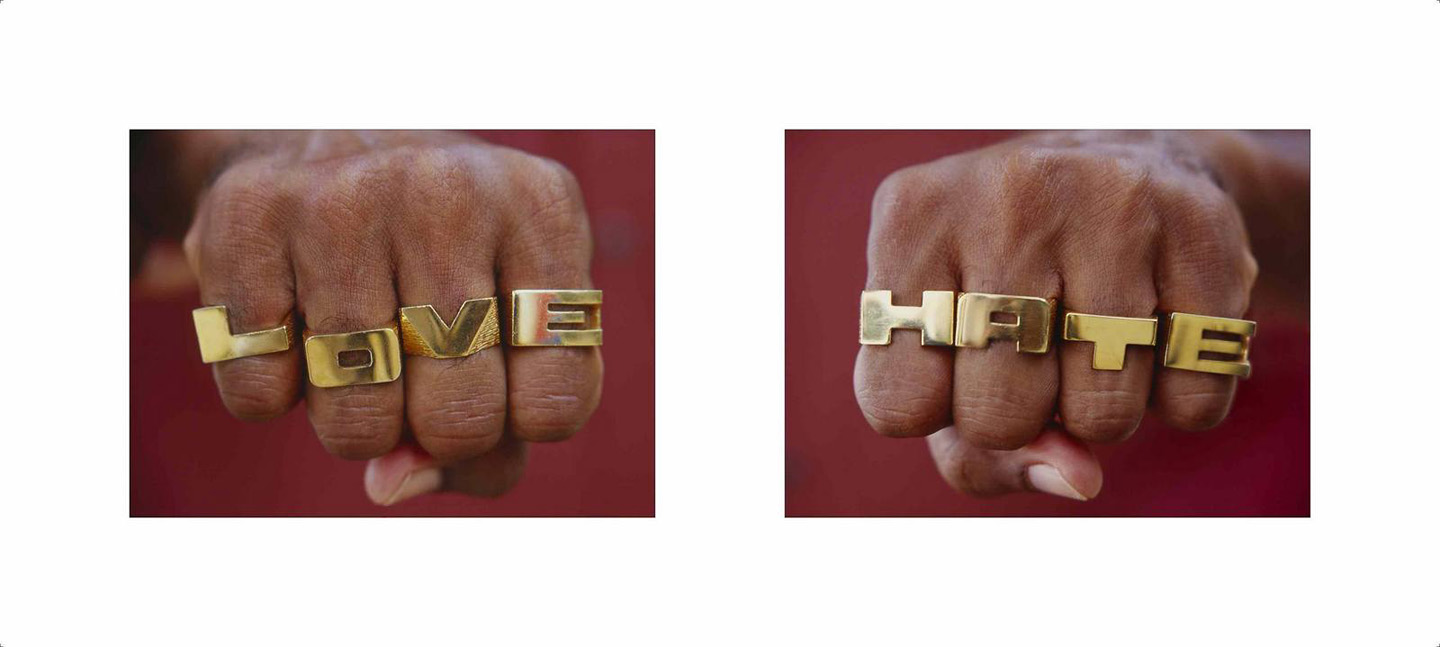

images: (cover 1) Jota Mombaça_Transition and Apocalypse_HAU_2019 (2) Isaac Julien, «Love Hate», 2006 (3) Barbara Prézeau Stephenson, «Le Cercle de Fréda», 2012, © Josué Azor (4) Tessa Mars, «Dress Rehearsal November Rituals», 2017 (5) David Frohnapfel, «Alleviative Objects», cover)

Dr. David Frohnapfel studied art history, comparative literature, and religious studies at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich and at the Universidad de la Habana in Havana. He received a Ph.D. degree from Freie Universität Berlin. His research focuses on decolonial theory, critical race theory, queer theory, affect theory, socially-engaged art, and Caribbean Studies. He worked as curator of The 3rd Ghetto Biennale in Port-au-Prince together with Leah Gordon, André Eugène, and Jean Herald Celeur, and curated the exhibition “NOCTAMBULES on Queer Visualities” on the occasion of Le Forum Transculturel d’Art Contemporain. Frohnapfel is also the author of Alleviative Objects. Intersectional Entanglement and Progressive Racism in Caribbean Art (2020) and part of the curatorial team of the exhibition “Love?” (2022) for the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Cologne.

The interview to David Frohnapfel is part of Kisito Assangni’s research on “curating as a phenomenological history of everyday life”:

Transitory conversations with reputable curators who engage positively with artistic practices driven by non-oppressive facilitation, alternative pedagogies, chronopolitics, and contemporary urgencies within the context of larger political, cultural, and economic processes. At this very moment in history, as well as raising some epistemological questions about redefining what is essential, this revelatory interview series attempts to bring together different critical approaches regarding international knowledge transfer, transcultural and transdisciplinary curatorial discourse. (Kisito Assangni)

Past interviews:

Kisito Assangni: interview to Matthew Bowman (Arshake, 22.07.2022)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Nadia Ismail (Arshake, 23.03.2022)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Mario Casanova (Arshake, 14.01.2022)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Nkule Mabaso (Arshake, 09.11.2021)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Lorella Scacco (Arshake, 20.07.2021)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Kantuta Quirós & Aliocha Imhoff (Arshake, 11.05.2021)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Adonay Bermúdez. Universal Truths Have no Place in Curating (Arshake, 08.06.2021)

Kisito Assangni, Kantuta Quirós & Aliocha Imhoff. Curatorial Methology as inter-epistemic dialogue (Arshake, 11.05.2021)

Kisito Assangni, Interview to Adonay Bermúdez. Universal Truths Have no Place in Curating (Arshake, 08.06.2021)