Milica Jankovic is a self-confident young artist, worldly but able to stay true to her Balkan roots. Montenegrin, now also Italian, Jancovic’s installations always push us beyond apparent reality to plunge us into a complex, multifaceted unconscious – sometimes dark, sometimes characterised by the intrusions of digital space, sometimes poised between the iconic and the sensational. Let’s listen to Milica in order to broaden our inner and spatial horizons, to shift the parallax of our gaze towards the art system, to revive a powerful and clear philosophical outlook.

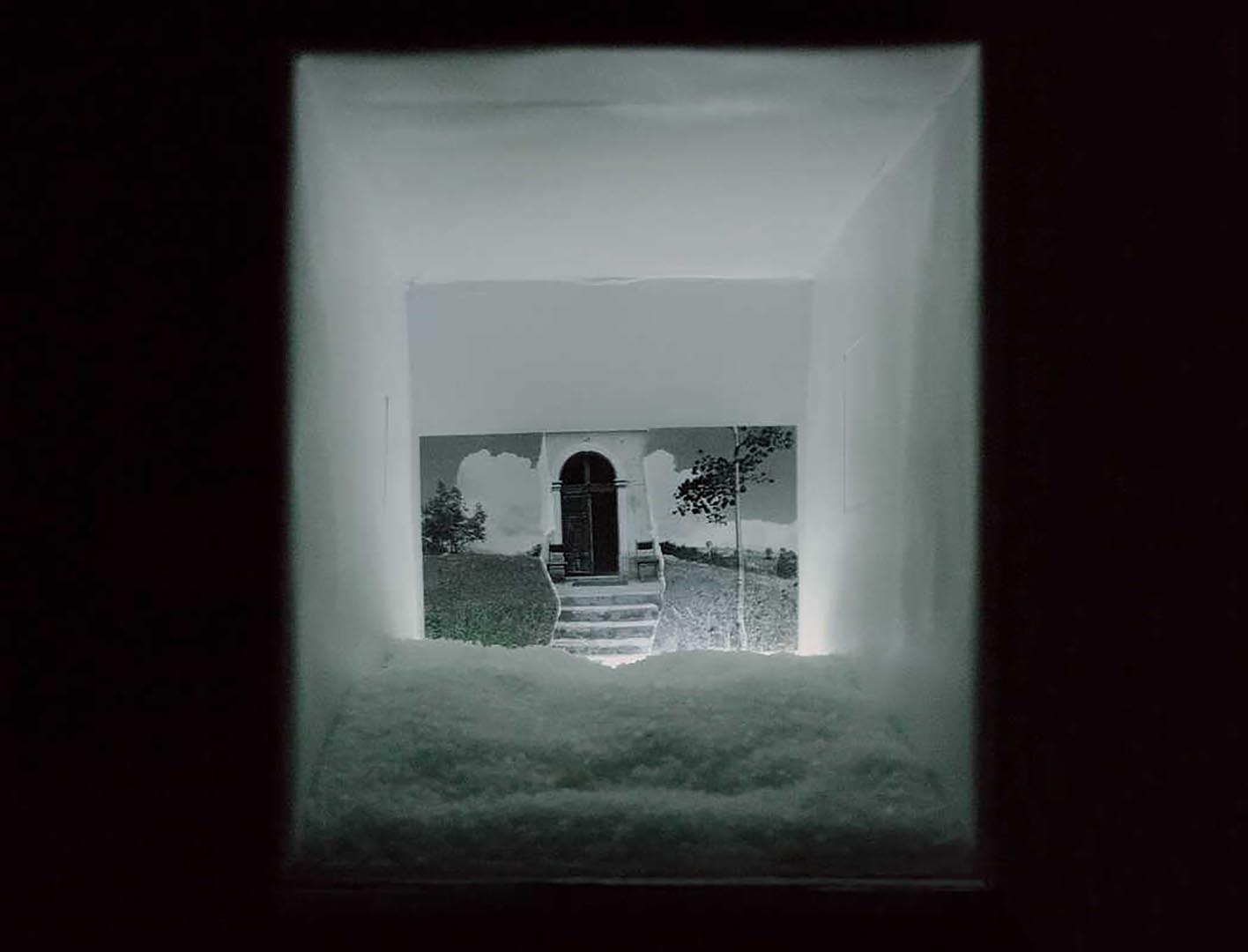

Fabio Giagnacovo: You often work on the concept of space and the relationship it establishes with the viewer. The Other relates to space, therefore to your works, which are often environmental installations. The spectator also relates to light, both inside and outside your works, and therefore to shadow – sometimes your own, sometimes that of your works. To give two contrasting examples: first, the enormous installation In the shadow of another we look for our own shadow, in the mirror of another our own mirror (quoting Borges) in which material – your wire works – and immaterial – moving light – continuously transform space, through shadow, transforming the visitor in the process; and then there is the tiny metaMONDI, alienating miniature environments that tell us of a life never lived and yet (re)presented, where, as you write, “external reality meets inner reality,” in a strongly characterising shadow that becomes a metaphor. You seem to prefer the sensory qualities of space to the physical ones, the place as a cryptic, philosophical ‘place of sensations’. Is that so?

Milica Jankovic: Your interpretation is very interesting and from this perspective I would say it reflects a careful analysis of my artistic journey. Although my work is based on the relationship between space and viewer, I think this is the side effect of the curiosity that drove me towards researching the space we inhabit and our surroundings, and how they can influence our perception, offer us different sensations and open us up to another experience. More importantly, it drove me towards researching how we can create those passages in which the evocative power of image, sound and smell (I’m referring to these in their ‘pure state’), first establish themselves in us and then reveal themselves to the outside world, unveiling their full potential. In answering the question, I would add that this space is largely related to and reflects the personal space we occupy (both mental and physical). I think that this continuous change between personal space and the space of the other has led me towards a further dialogue between the material and the immaterial in the works themselves, in a continuous change that leaves the viewer open to other worlds.

This process transforms not only the space itself (understood as the work) but also that of the visitor, who becomes an integral part of the work, experiencing a direct relationship with their surroundings. In this way, the work exists through the visitor, or rather, thanks to the person who completes it.

As you have already noted, this applies to both miniature environments and large-scale works but, at the end of the day, what interests me most is the feeling that is established between the viewer and the work. I think it’s important to give the other person a chance to complete the work, to become part of it. It’s an unpredictable ‘operation’ where one cannot anticipate how the work will be interpreted, experienced or what it will lead to and in what way it will benefit the viewer. In essence, however, always returning to the same argument, you understand that, in reality, perceiving and experiencing the other (the work or/and the space) always depends on ourselves.

So, yes, you could say that I’m interested in exploring place as a ‘place of sensations’ and creating experiences through my artwork. In conclusion, I try to encourage a deep emotional and intellectual connection between the viewer and the environment that has been created.

In all your works, we can see that your aim is to get to the bottom of things, reveal their essence, never, for example, being seduced simply by the sensuality of the icon. You also often use new technologies by experimenting with their aesthetic qualities (digital immateriality has many features in common with our unconscious) but also by using them as a functional tool (a brush stroke to depict contemporaneity). How do these new technologies help you in your artistic process? And how utopian is it to want to reach the essence of things?

Although new technologies play a significant role in my artistic process, particularly in recent years, I see them as a means through which I can address and explore the world in ways that would otherwise be inaccessible. Perhaps, in this case, the unreadable ways (but also worlds) that new technologies make it possible to detect should also be pointed out. I would say that the spatial experiments that allow these means help me to create the places where future experiences take shape, even in tangible ways. It’s not easy to work with these tools because you must know the language but, above all, you must also possess an awareness and critical capacity when approaching them since, like any new medium, they have the ability to easily seduce us. One must, therefore, be cautious not to fall into the trap and not be “bewitched” by the allure of current events and trends. And now we arrive at the second part of your question.

When seeking or going towards the essence of things, there’s always an element of challenge and perhaps utopia. Achieving the essence of a concept or experience is an ambitious and perhaps elusive goal, but it’s precisely the search for this essence that fuels my artistic practice and being. However, even though the essence itself may remain elusive, the pursuit of it is profoundly meaningful.

You were born in Montenegro, but I find it hard to think of you as exclusively Montenegrin, as you are constantly travelling between countries in Europe and beyond, also taking up various artist residencies. At the same time, however, I find it hard not to think of you as Montenegrin, in the sense that you are strongly characterised by a genius loci. What does it mean for an artist to travel? How important are residences? You write in your statement: “I was born in Cetinje, which can be defined more as a place of passage than a city. The mountains that define it also unconsciously shaped my thinking.” How did those mountains shape your thinking, and in what way did they somehow become part of your artistic process?

You were born in Montenegro, but I find it hard to think of you as exclusively Montenegrin, as you are constantly travelling between countries in Europe and beyond, also taking up various artist residencies. At the same time, however, I find it hard not to think of you as Montenegrin, in the sense that you are strongly characterised by a genius loci. What does it mean for an artist to travel? How important are residences? You write in your statement: “I was born in Cetinje, which can be defined more as a place of passage than a city. The mountains that define it also unconsciously shaped my thinking.” How did those mountains shape your thinking, and in what way did they somehow become part of your artistic process?

After almost ten years abroad, I also find it hard to think of myself as exclusively Montenegrin, but important events shaped me there and, thanks to them, I’m happy to be Montenegrin. I think it’s this crazy urge to always go somewhere else that has pushed me into moving constantly. All these years have been full of exhibitions, residencies in Europe, China and also in the United States, but I believe that Italy has been the most important place for my personal and professional growth. Probably because it was precisely in Italy that I realised the importance of the genius loci you speak of, which made me realise how much the shape of the mountains of Cetinje and this metaphorical need to climb them, and see beyond them, pushed me towards who I am today.

On the one hand, it was a great blessing (although I don’t know if that was all it was) to be able to live all the experiences that came with each trip. They certainly had a significant impact and I think they aren’t something that can be easily related. Experiences only ask to be lived to the full. The opportunity to explore new environments, cultures, stories and perspectives has enriched my cultural and intellectual background, contributing to a greater open-mindedness and the ability to see the world from different angles (how nice to think and dream in different languages!). Above all, this year has been significant for my professional growth, but I would add that in this process it’s essential to make choices, otherwise there’s a risk of getting lost among the thousands of possibilities which we often unwittingly adapt to. This is why the residencies I choose are mainly aimed at my professional growth and linked to the design and creation of future works.

You opened a cultural association in Montenegro a few years ago, which aims to create a fruitful dialogue between young international and Montenegrin artists: Atelie 22. The association, as explained on the website, has carried out various workshops, calls for artists, residencies and so on. Can you tell us about the joys and sorrows involved in such a choice? What have your greatest satisfactions been and what, if any, the most bitter disappointments?

Atelie 22 has been running since 2020 and, from this year, we also have a publishing house, which bears the same name. It wasn’t easy to develop a cultural association project, but my desire to deepen and develop my experiences abroad was such that this choice came naturally to me. I felt the need to contribute, not only as an artist, but by creating an ecosystem that could offer new educational and exhibition opportunities.

The biggest challenge was curating the multimedia art festival Re/Shaping The City. It was the first year of Covid-19 and the idea of the festival was born at a time when galleries and museums were closed to the public. At that moment, I was faced with 1,200 square metres of public space, with 20 artists from all over Europe, including Montenegro, and a whole host of problems related to preparing the exhibition, curating and installing the works over a long period of time. The main idea of the festival was to invite different artists to interact with the public space, creating site-specific installations.

The best thing about that period was the mutual exchange between foreign and Montenegrin artists. This cultural and creative dialogue was incredibly rewarding and a way for everyone to broaden their artistic horizons. The organisation was stressful but, at the same time, extremely rewarding. I’m lucky enough to never feel the stress that comes with organising, carrying out and realising projects. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have been able to do anything!

I’m convinced that, in our own small way, we’re contributing to the growth of the art scene and public awareness, both through the festival but also through publications and translations of contemporary art books. Of course, managing both of these requires financial resources and a constant search for funding. Although dealing with bureaucracy and financial management is complex, to date we have managed to obtain the support of the Montenegro Ministry of Culture and several European Foundations, which have enabled us to carry out very extensive projects. The ongoing challenges are, in fact, an integral part of the experience and give one the opportunity to grow and improve over time.

You trained as an artist in Montenegro and then in Italy and came into contact with different artistic circles around the world. What do you think are Italy’s critical issues in this sector when compared to other countries? When graduates leave university, they find a job, perhaps take training courses to strengthen their skills and then progress professionally and economically throughout their lives. In your opinion, in the arts, why are we only faced with unpaid jobs and ridiculous internship opportunities bordering on exploitation?

Valuing artistic work is essential and, for this reason, I believe it’s crucial to promote policies and initiatives that properly recognise the contribution of artists to society.

We certainly live in a society, in Europe, where we are led to believe (first and foremost) that culture should be something that cannot be monetised: ‘Being’ an artist should be a matter of talent, which brings dedication and passion with it, rather than being focused on making money. By contrast, in the United States, culture is essentially profit, which is why it must respond exclusively to market logic. Both have their advantages and merits, but also flaws and shortcomings.

The issue of underpaid internships fits into this context, involving different disciplines in the arts and humanities. The problem is exacerbated as artists often struggle to find a proper place in contemporary society, a problem that is unfortunately not limited to Italy. The need to strengthen links between the artistic world and the business or market sector is a real challenge that must involve all countries.

At a time when rapid changes are fuelled by ‘new’ technologies, it’s clear that this will require a change of perspective. What I can say, from my own experience, is that this will require a new way of approaching art and the market itself. A phenomenon that is slowly taking shape.

Today, more than ever, I believe that the artistic community plays a crucial role in this phenomenon. In particular, I attach great importance to those artists who integrate their experimentation in collaboration with other disciplinary fields in order to direct their product into different areas, without limiting themselves to an aesthetic objectification of the ‘new’ media.

One does not need to be a prophet to understand that evolution is inevitable, especially since so many artists have remained on the fringes of a system tied only to commercial dynamics that privilege and emphasise the aesthetic object. Certainly, if we want to change something, we have to start with ourselves, but it’s encouraging to note that Europe, with its projects, offers some opportunities to deal with this changing context, unlike other realities I have known.

Images (cover – 1) Milica Jankovic, Illustration by Nikla Cetra (2) Milica Jankovic, «In the shadow of another we look for our own shadow, in the mirror of another our own mirror»; large-scale wire sculpture installation with repetitive light movements; variable dimensions; solo exhibition curated by Ljiljana Karadžić at Galerija Art, Podgorica, Montenegro (2022) (3) Milica Jankovic, «metaMONDI», diorama in cardboard boxes with internal lighting system; miniature sculptures/objects – variable dimensions; solo exhibition in the GABAYoung gallery, Macerata, Italy, curated by Giulia Perugini (2019) (4) Milica Jankovic, «metaMONDI», diorama in cardboard boxes with internal lighting system; miniature sculptures/objects – variable dimensions; solo exhibition in the GABAYoung gallery, Macerata, Italy, curated by Giulia Perugini (2019) (5) Milica Jankovic, «Take Me Back Home» (detail); site-specific installation with Augmented Reality; public installation made in collaboration with software engineer Martynas Januškauskas (LT) – Re/Shaping the City festival, Cetinje, Montenegro (2021). (6) Milica Jankovic, «Inherited Memory»; 3 frames of the video installation designed on the mirror glass folia, YVAA – Young Visual Artist Award (‘Milčik’), ISU, Montenegro (2022). (7) Milica Jankovic, Illustration by Nikla Cetra

“Survive the Art Cube” is a series of interviews with artists from different generations. The title borrows from Brian O’Doherty’s most famous book to echo its critical slant. It aims to better understand how these artists perceive the analogue-digital space in which we are immersed and our contemporaneity, what sense and importance artistic space has today and what sense it makes in our present to make an artistic journey. Dark times call for reflection on reality and only artists, perhaps, can open our minds.

Past interviews:

Interview to Giulio Bensasson, Arshake 18.01.2024

Interview to Eva Hide, Arshake, 28.12.2023

Interview to Federica Di Carlo, Arshake, 16.12.2023

Interview to Giuseppe Pietroniro, Arshake, 07.12.2023

Interview to Francesca Cornacchini, Arshake, 14.11.2023

Interview to Enrico Pulsoni, Arshake, 09.11.2023

Interview to Marinella Bettineschi, Arshake, 15.10.2023