The research by Elena Giulia Abbiatici on the “Eternal Body. Human senses as a laboratory of power, between ecological crises and transhumanism”, continues, today in dialogue with Tom Tlalim, artist, musician and writer whose work explores the relation between sound, technology, ideology subjectivity.

Elena Giulia Abbiatici: Where does the idea of Tonotopia come from?

Tom Tlalim: Tonotopia came from a need to explore the borders of sound and listening. I hoped to try and listen beyond dominant narratives and aesthetics and question my own ableist preconceptions. Asking what art forms might emerge from the growing availability of technologically mediated sensory perception?

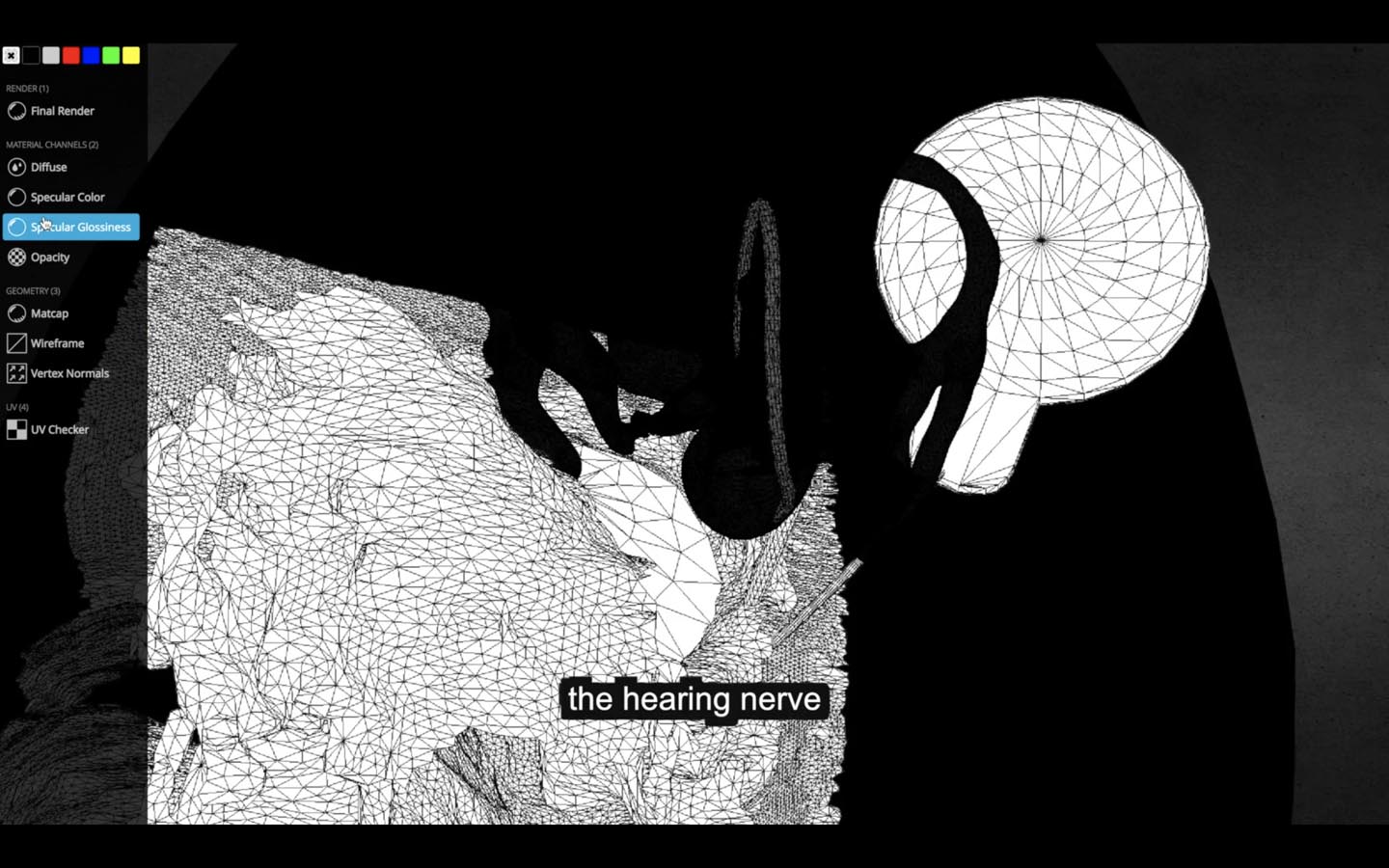

Cochlear Implants (CI) offer a unique form of hearing. They replace the apparatus of the ear with an artificial system that transmits signals directly to the hearing nerve. This begs the question, what is sound art when we listen through different ears?

The project investigates new aesthetics that emerge from sensory technologies and how access to art and culture be improved? I was also curious about the new sphere of sensory bio-politics created by mediated sensory experiences. Reading Seth Kim-Cohen’s ideas around a ‘non-cochlear’ sonic art gave weight to these questions. Kim-Cohen called for a sonic art that explores areas outside of pure perception. This has a literal meaning here because as the CI bypasses the cochlea and re-evaluates our share experiences of what art sounds like.

Mara Mills’ interview with pioneer cochlear implant recipient Charles Graser and the documentary’ Sound and Fury’ (Josh Aronson, 2000) were an inspiration, alongside Pauline Olivero, Brandon LaBelle, Suzanne Cusick, Steve Goodman and others.

As I was writing about the political use of sound in the Middle East, I wanted to ask where political border spaces lie within our sensory body? How did the inner, physical space of the ear become a contested bio-political border space where CI manufacturers, medical care industries, big tech, health services and state legislature all compete for influence? I wanted to hear from CI users themselves how they experience listening? How do they feel about social relationships and their love of music? What was their consent process, and how much did they know about what it would be like beforehand? It became clear that a conversation with cochlear implant users is the only way to learn about these things.

I was fortunate to start a dialogue with Rory Hyde, the curator of architecture and urbanism at the V&A, who had put me in contact with the charity RNID for hearing loss. I had an opportunity to pitch the project to the curator of architecture and urbanism, Rory Hyde, who invited me to develop the project in residency at the V&A museum and connected me with RNID, the UK’s national hearing loss charity.

RNID helped spread the call out to their cochlear implant community. The stories of the six participants who have joined the project breathed life and depth into the questions and made them infinitely more urgent and relevant.

The project was immensely helped by advice from Professor Maria Chait from the UCL EAR Institute in the UK and Professor Mara Mills from NYU Steinhardt.

How do you conceive, after your relevant period of research with CI users, the idea of recovering, extending, amplifying… our senses and having a new experience of reality?

I resisted the temptation to fetishise the device itself as an object or amplify it as if directly as a futuristic, sensory augmentation device or a cybernetic sense because this would have been too didactic and inaccurate. The idea of medicalising or remedying the senses is problematic because it presumes that there is an ‘able’ or ‘healthy’ form of hearing and that anyone who does not conform to it is less able. Working on this project, I realised that the spectrum of hearing and listening forms is extraordinarily diverse and should be acknowledged as such.

Every user I had interviewed described perceiving things in their unique way, which is impossible to fully communicate, but can be described through stories. I wanted to tap into this diverse richness of language and bring these to the surface in the project as part of the non-cochlear art.

Listening can sometimes be visual. British Sign Language speakers, for example, often identify as being of a particular group who share a language. Similarly, comparing CI hearers with ableist notions of audition does not make sense as I’ve met so many listeners, each with their own specific and unique hearing ability.

How was it working with the IC user team? How urgent is the need/will for them to state and tell their personal story and case?

My hypothesis was quite naïve initially, as I realised I know so little about the reality of using these very complex devices. For example, not all of the electrical signals emitted by the device will be received by the user’s hearing nerve. Also, the user’s hearing will be affected by the history of their hearing which can affect how they learn to listen with the device.

I was struck that it was difficult, if not impossible, to know how someone else really hears or how they learn to recognise different sounds based on the sensory information they get.

One of the participants was an enthusiastic young activist in the community, and his attitude was highly positive and optimistic. He loved the gadgets and was constantly actively engaged in his learning process. He told about the moment when he heard a repetitive beeping sound while camping outside. He didn’t recognise this and discussed it with his family when they finally realised it was a chirping cricket. He described how, suddenly, his neurons seemed to connect, and he began to hear the sound as a cricket.

Another participant described hearing noisy rhythmical sounds while visiting a museum and seeing a video of a piano player as he turned around. Again, he explained how the visual image and the knowledge that this was a piano made his hearing ‘learn’ that sound.

These stories were great to hear because they explain simply how we constantly listen with our eyes, verifying the sources from which sounds are emitted. This chimed well with Brian Kane’s writing on the acousmatic situation in his extraordinary book ‘Sound Unseen’.

What did they discover through their experience with Tonotopia and what did you discover through them?

The people who have decided to participate in this project shared their unique perspective on life with a cochlear implant. In a way, they were all activists, aware of the importance of their stories to the wider CI community and prepared to go through a process with me.

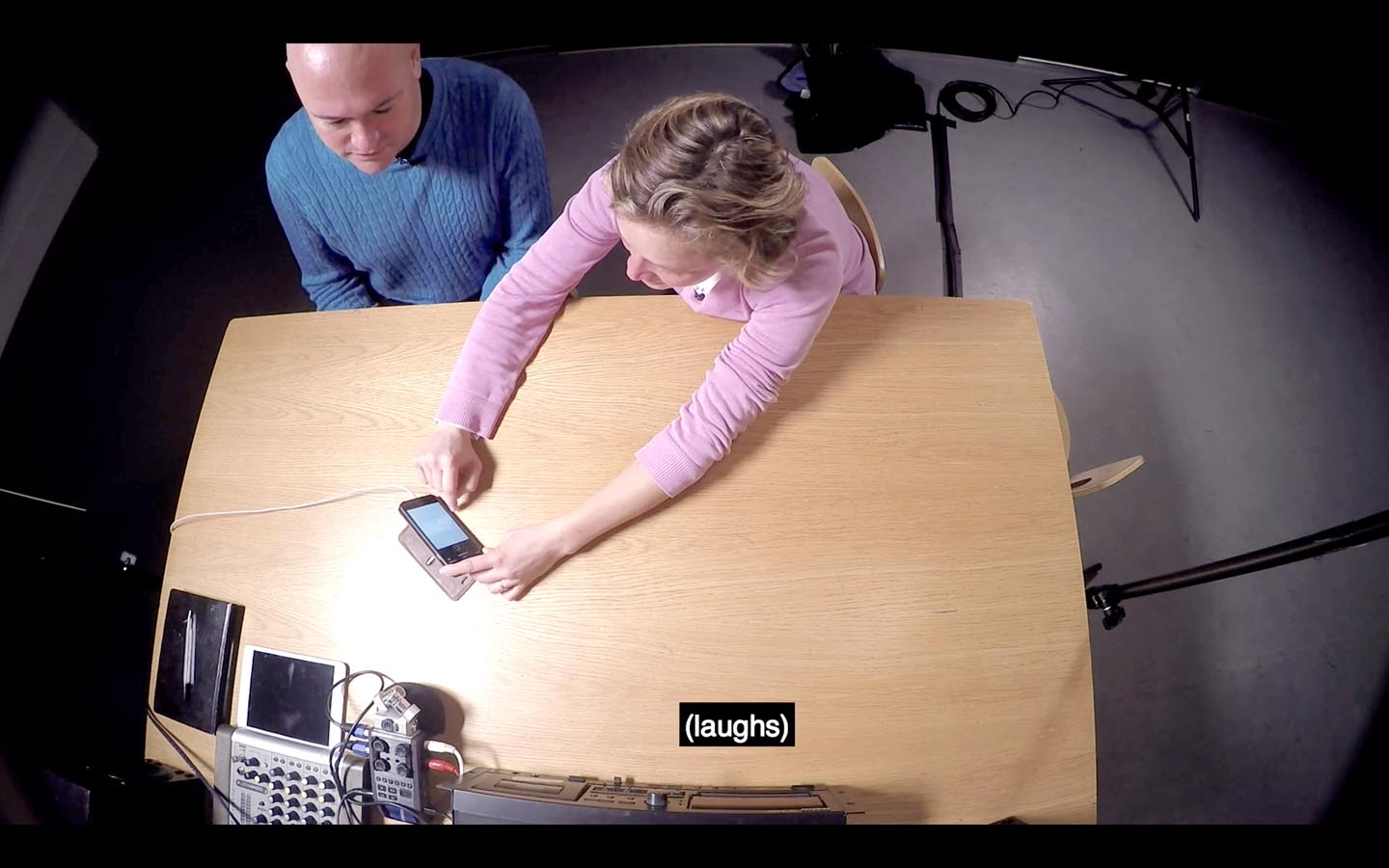

We have set up a video recording studio at the V&A where I had tried to create a quiet and intimate environment. While everything was being recorded, participants needed to be able to hear and be listened to while telling their stories.

Participants were incredibly generous with their stories. It seemed like the occasion of a public exhibition was a chance to share their experience with the wider community, away from the medical and CI industry setting. These stories were important because due to the novelty of this technology, CI users have not had the time to develop a strong sense of group identity, and the ability to hear each other’s stories in the exhibition became one of the substantial impacts of the project.

Some participants opened up about difficult experiences they’d had during and after the operation and when the device was switched on. One participant gradually lost her hearing and received the CI later in life after a long career as a geography and music teacher. She spoke of her sense of loss and how receiving the implant had changed her relationship with music. Music sounded different with the implant, and she’d started to actively explore music with rhythmical emphasis instead of the kind of classical harmonic textures she’d enjoyed before.

She was extremely proactive during the interviews and brought in an extensive collection of tree branches for the recording. She told me about her regular outdoors walks, mapping sounds and recording them on her mobile phone like a kind of hybrid sonic Dérive.

She has a strong memory and capacity to interpret music and re-learn it with her new form of hearing as if it were a new musical instrument.

Her story is quite different from that of young children who have received an implant during the first 3-5 years of their lives. This mode of hearing and listening has been integrated into their process of language development.

… to be continued…

images: (cover 1 -2) Tom Tatlim, «Tonotopia.Listening through Cochlear Impants», V&Albert Museum, London 2018 – 19 (3) Tom Tatlim, «Tonotopia. Listening through Cochlear Impants», V&Albert Museum, London 2018 – 19, interview with Rachael Cunningham, immage: Tom Tlalim (4) om Tatlim, «Tonotopia.Listening through Cochlear Impants»,screenshot (6) Tom Tatlim, «Tonotopia.Listening through Cochlear Impants», V&Albert Museum, London 2018 – 19 (5) Tom Tatlim, «Tonotopia. Listening through Cochlear Impants», V&Albert Museum, London 2018 – 19, interview with Sarah Smith, image: Tom Tlalim

Tom Tlalim is an artist, musician and writer whose work explores the relation between sound, technology, ideology subjectivity. His art practice explores sonic artefacts, voices and spaces as ideological devices. His PhD research at Goldsmiths, titled “The Sound System of the State”, was funded by the Mondrian Foundation for the Arts. He holds MAs in Composition and Sonology, and currently works as a Senior Lecturer at the University of Winchester. His work received numerous grants and awards and is exhibited internationally. Recent exhibitions include ‘Tonotopia’ and ‘The Future Starts Here’ at the V&A in London, ‘Forensic Architecture’ at The Venice Architecture Biennale (with Susan Schuppli), “Art in the age of Asymmetrical Warfare” at Witte de With, Rotterdam, “Hlysnan” at Casino Luxemburg, the Marrakech Biennale, and Stroom The Hague. His film “Field Notes for a Mine” was nominated for the Tiger award at the International Film Festival Rotterdam. His regular collaborations with the choreographer Arkadi Zaides are performed widely to a critical acclaim.

The interview to Tom Tatlim ”is part of “Eternal Body. Human senses as a laboratory of power, between ecological crises and transhumanism”, curated by Elena Abbiatici. This rearch has been organised thanks to the support of the Italian Council (IX edition 2020), an international programme promoting Italian art under the auspices of the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities and for Tourism.

Previous articles:

E.G.Abbiatici, The Posthuman, Live beyond individual, species, death, Arshake 09.02.2022

E.G. Abbiatici, Digital Acoustic Devices. Can technological devices correct the effects of noise pollution and the obsolescence of our senses?, Arshake 02.02.2022

E.G.Abbiatici, Interview to Abinadi Meza, Arshake 20.01.2022

E.G.Abbiatici, Interview to Mario Matta, Arshake 23.11.2021

E.G. Abbiatici, The political component of noise in the artistic practices of the last century: Pt. I ( 14.10.2021) e Pt. II, 14.10.2021

Elena Giulia Abbiatici, Smell as a transcendent sense. The Role of the Olfactory System in a society focused on the Ethernal Body, Arshake 02.08.2021

E.G.Abbiatici, For an Olfactory Bio-politics. Pt I and Pt II

E.G. Abbiatici, Exellent (artificial) noses, Arshake, 04.05.2021

E.G. Abbiatici, Right Under Your Nose, Arshake, 03.03.3021

Partners of the project: Arshake, FIM, Filosofia in Movimento-Rome, Walkin studios-Bangalore, Re: Humanism, Unità di ricerca Tecnoculture – Università Orientale – Naples GAD Giudecca Art District-Venezia, Arebyte – London, Sciami – Rome. “Eternal Body. Human senses as a laboratory of power, between ecological crises and transhumanism” is supported by the Italian Council (9th Edition, 2020), program to promote Italian contemporary art in the world by the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity of the Italian Ministry of Culture”.